In the UK today, only 1% of babies are exclusively breastfed by the time they are six months old, as recommended by the World Health Organization. Even fewer infants are breastfed by their first birthday; extended breastfeeding, nursing beyond that age, is rarer still. Yet it was not always so. In Elizabethan times, children could be nursed until they were over two or even three years old, as Shakespeare illustrated in Romeo and Juliet:

On Lammas-eve at night shall she be fourteen;

That shall she, marry: I remember it well.

‘T is since the earthquake now eleven years;

And she was wean’d, I never shall forget it,

Of all the days of the year, upon that day

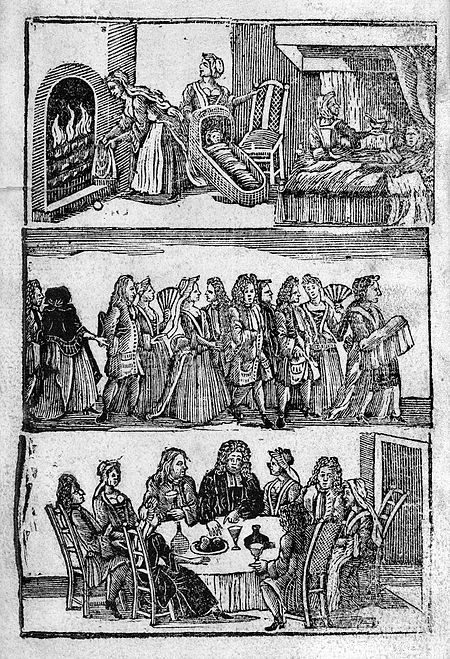

This scene highlights the love Juliet’s nurse felt for the girl. Wet nurses could develop strong bonds with their charges, although their role was often contested. Juliet was three years old when she was weaned by the nurse, who had to use wormwood on her nipples to stop her body from producing milk. Shakespeare often mentioned herbs like these in his plays, as most of his contemporaries would be familiar with them.

For I had then laid wormwood to my dug,

Sitting in the sun under the dove-house wall;

My lord and you were then at Mantua –

Nay, I do bear a brain – but, as I said,

When it did taste the wormwood on the nipple

Of my dug and felt it bitter, pretty fool,

To see it tetchy and fall out with the dug!

From what medical writers tell us, babies were usually breastfed for longer in continental Europe than in Britain; keep in mind that Romeo and Juliet is set in Verona. Still, an English person watching the play in a London playhouse wouldn’t have found Juliet’s weaning age unusual. Most 16th and 17th century medical writers, such as Jacques Guillemeau and Jane Sharp, would have advised that infants should nurse for around two years. But why was that?

Breast milk was believed to have powerful medical properties as a remedy, but it was also considered the best nourishment for young children, as it would make them strong and healthy, and transmit love and security. Not too different from the advice new parents receive today!

In the early modern period, it was thought that when someone became pregnant, they would stop menstruating because the blood would feed the infant in the womb. After birth, the same blood would travel upwards in the body, being concocted (literally cooked) and turned into breast milk, to keep on nourishing the baby. This understanding of the human body was deeply embedded in the humoral theory: Guillemeau described breast milk as ‘nothing else but blood whitened’.

According to the midwife Jane Sharp, babies should feed as often and as much as they liked in their first months – what we today call feeding ‘on demand’. As for weaning, she recommended her readers to wait until most of the baby’s teeth had appeared, especially the eye-teeth (canines), which usually come in when babies are between 16 and 20 months old. This meant that the child was ready for solid foods – though usually, a transition phase preceded more robust foods like meats, starting roughly around 8 months old. For Sharp, weaning shouldn’t be abrupt, but a gradual process. Whenever possible, it should vary according to the child’s bodily complexion and temperament:

‘the stronger the child is, the sooner he is ready to be weaned; some at twelve months old, and some not till fifteen or eighteen months old; you may say two years if you please, but use the child [get the child used] to other Food by degrees, till it be acquainted with it.’

These foods were also used for younger children when breast milk was not available, complementing animal milk. Pap was a mix of warm water and flour, or bread made soft by the addition of milk, water, or eggs. Panadas were also an option and consisted of cereals cooked in broth, similar to porridge. Both were given as supplements to children fed with animal milk as well as on their own. Still, the results could be mixed: the younger the baby, the more likely that they might die without breast milk.

Until the industrial revolution and the widespread use of bottles and, later, the development of artificial feeding through infant formula, breast milk was virtually the only option for babies. Medical writers like Guillemeau and Sharp urged readers to feed children with breast milk – whether it should be the mother or a wet nurse to do so is a different matter. Purees should be introduced little by little and, eventually, solid foods as well. Weaning should be gradual whenever possible. It might surprise you how contemporary (and sensible!) this advice sounds. But, like Juliet’s nurse reminds us, those who care for children have always tried to do their best to help them grow into strong and healthy adults. What we call ‘extended’ breastfeeding today was for centuries just plain ‘breastfeeding’, no adjective needed. With people being shamed for extended breastfeeding today, it might help to look back and see how things were in the past. After all, breastfeeding Juliet had been for the nurse

‘An honour! Were not I thine only nurse, I would say thou hadst suck’d wisdom from thy teat.’

Too bad about how the story ended. Oh well! There wasn’t much the nurse could do, and it wouldn’t be a tragedy otherwise, would it?!

References:

Jacques Guillemeau, The Happy Delivery of Women (London, 1612).

William Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet, The Riverside Shakespeare, edited by G. B. Evans (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1974). (First published in 1597.)

Jane Sharp, The Midwives Book (London, 1671).

Further Reading:

David Cressy, Birth, Marriage, and Death: Ritual, Religion, and the Life-Cycle in Tudor and Stuart England (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997).

Valerie Fildes, Breasts, Bottles and Babies (Edinburgh University Press, 1986).