‘He was trying to gather up the scarlet threads of life and to weave them into a pattern; to find his way through the sanguine labyrinth of passion through which he was wandering’

Humours are everywhere. People can react cholerically to an insult, music can make us melancholic, time with friends can lift our spirits, and we can be in good or bad humour. This is not surprising. The humoral theory has a long history, beginning with the Greek Hippocratic writers in the fifth century BC, being reinterpreted by the Roman physician Galen in the second century AD. Humorism survived thanks to its translations into Latin in the medieval period and started to be taught in the newly founded universities. Later, the humoral theory was incorporated into vernacular medical texts in the early modern period. It remained the primary way to conceptualise medicine and the body until well into the nineteenth century.

For over two millennia, humorism (or humoralism) was the framework within which people thought about and practised medicine, especially in the West. It is the backdrop for most of our discussions about the history of medicine and gender, which is why it is such an important topic. So, what were the humours?

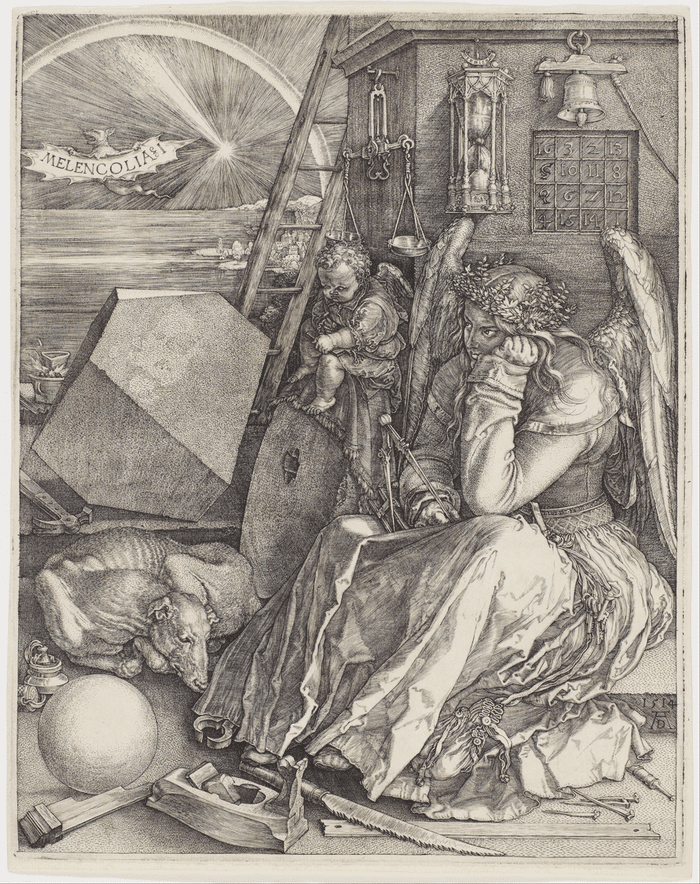

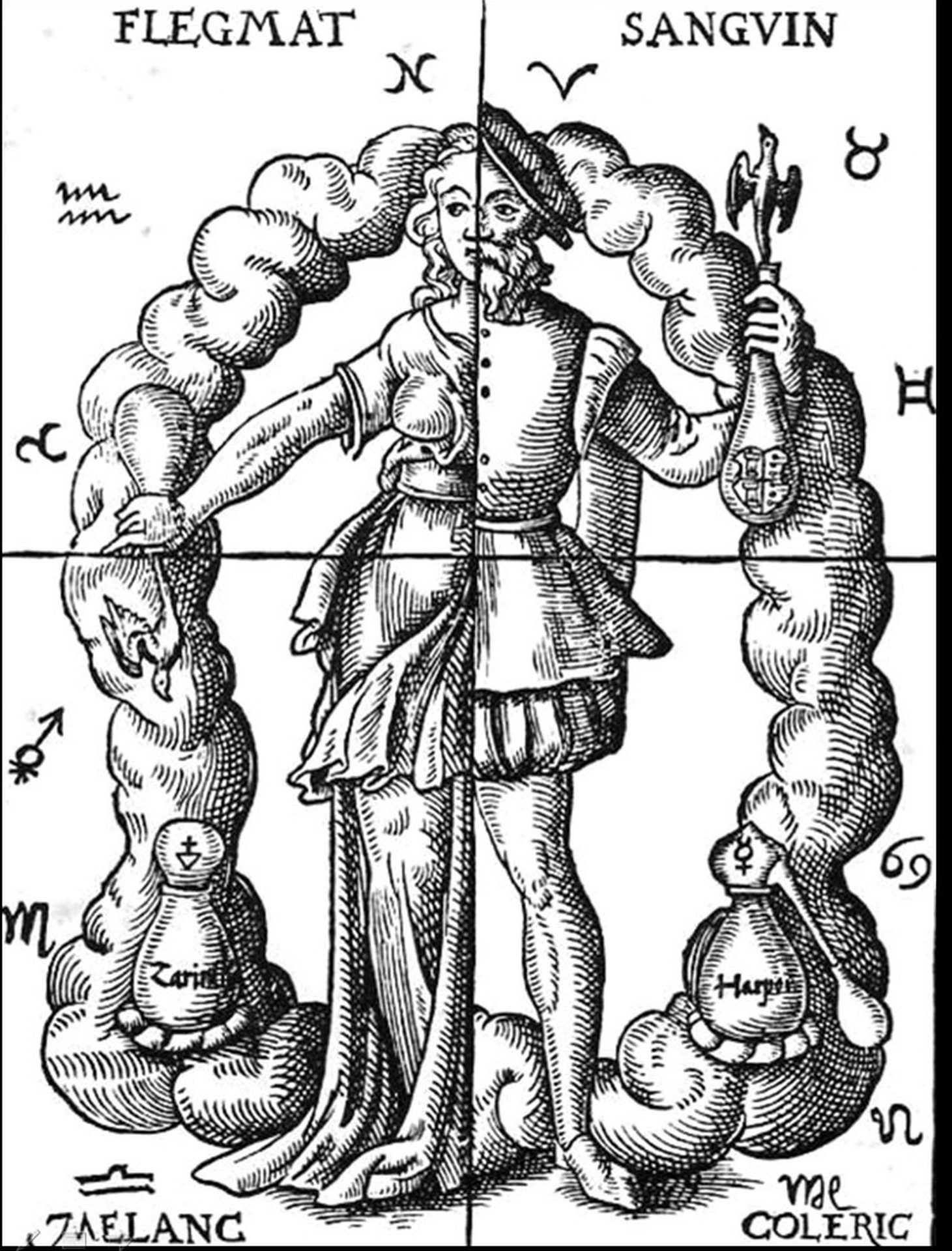

The humours were fluids or spirits (humon in Greek means fluid) concocted in the stomach in the heat of the digestion, which circulated in the body. There were four humours: blood, phlegm, yellow bile (choler), and black bile (melancholy). All bodies contained the four humours but in different proportions, which could vary according to gender, age, and the season of the year. Each person had a different combination of humours, which determined their temperament, personality, and physical health: humorism saw the mind and body as deeply connected. This is why we still have adjectives such as melancholic, choleric, sanguine, and phlegmatic to describe people.

The humours were associated with the natural world, such as seasons and elements, but they also corresponded to a life stage and a specific organ. This web of connections was the basis for how illnesses would be treated. Foods deemed hot, such as spices and red meat, could be used to treat an excess of phlegm or melancholy, heating the body. (For the same reason, they could act as aphrodisiacs.) On the other hand, cucumber and melon would be appropriate to counteract an excess of yellow bile. Physicians could also advise patients to change their location, going somewhere where the weather was more suited to treat their condition.

| Humour | Blood | Phlegm | Choler (yellow bile) | Melancholy (black bile) |

| Life Stage | Childhood | Old Age | Youth | Maturity |

| Season | Spring | Winter | Summer | Autumn |

| Element | Air | Water | Fire | Earth |

| Temperament | Sanguine | Phlegmatic | Choleric | Melancholic |

| Characteristics | Hot/Moist | Cold/Moist | Hot/Dry | Cold/Dry |

| Organ | Liver | Lungs | Bladder | Spleen |

| Personality Traits | Brave Hopeful Playful | Calm Patient Indolent | Impatient Ambitious Restless | Quiet Pensive Despondent |

| Astrological Body | Jupiter | Moon | Mars | Saturn |

The delicate balance of humours determined a person’s natural good health; therefore, illness was contra-natural, often resulting from a humoral imbalance. Besides changes in their diet and environment, physicians could prescribe herbal remedies to counteract their patient’s condition. Moreover, if a humoral excess or lack caused illness, physicians recommended treatments such as enemas, emetics, purging, and bloodletting to restore the lost balance. Besides that, they gave patients specific advice about diet, exercise, and sleep, which might help rebalance their humours. Some of these medicines might shock us today – the use of leeches to treat haemorrhoids comes to mind! – but they mainly consisted of empirical knowledge adapted to fit the humoral understanding of the body.

For instance, menstruation was deemed essential for women of fertile age, as it was the body’s natural purgation. This is why amenorrhea (the lack of menstruation) was usually considered a serious medical concern, as blood would accumulate in their bodies and cause illness. Herbal remedies to stimulate uterine contractions and provoke menstruation were ubiquitous in medical texts: saffron, parsley, pennyroyal, cinnamon, cyclamen, and mugworts were some of the ingredients in these formulas.

Humorism changed through the centuries, combining local influences and merging traditions. However, for centuries, the four humours’ paradigm was orthodoxy among physicians, surgeons, midwives, and patients alike. It was challenged at times, such as by the rise of chemical medicine and Paracelsianism in the sixteenth century. Still, it remained central to how the body was understood in premodern times. It was a deterministic system: people might treat illnesses but not change their physical and psychological makeup.

Humours do not survive only in our language. Humorism underpinned how the body was understood, both in physiological and psychological terms, for centuries, until the germ theory of disease supplanted it. Humours went beyond the medical domain, shaping how we think about the body and surviving perhaps most clearly in the arts and literature. For instance, as Shakespeare’s Richard II asked people to achieve a bloodless resolution to their conflict, he referenced physicians’ bloodletting practices. This play on words between purging excessive blood and a bloody fight would have been clear to Shakespeare’s contemporaries:

Wrath-kindled gentlemen, be ruled by me;

Let’s purge this choler without letting blood:

This we prescribe, though no physician;

Deep malice makes too deep incision;

Forget, forgive; conclude and be agreed.

After the Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution, a new mechanical understanding of the body, conceptualised as a machine composed of parts that could be disassembled, replaced the humoral system. The germ theory became the primary way to understand diseases, made possible by technological advances and more precise microscopes in no small measure. However, we have also seen a return to a more holistic understanding of the body over the last fifty years. Medical practitioners and patients alike have started to explore alternative medical models inspired by traditional Chinese and Ayurvedic medicine, which consider individuality and understand the body as a whole. This is not a return to humorism as it used to be centuries ago; still, it is striking how Hippocratic doctors would approve of this paradigm change.

References:

Galen, De Temperamentis. Translated by P. N. Singer and Philip J. van der Eijk (Cambridge: 2018).

Hippocrates and Heracleitus. Nature of Man, Regimen in Health, Humours, and Others. Translated by W. H. S. Jones (Cambridge, MA: 1931).

Jacques Jouanna, Hippocrates (London: 1999).