How would you go about learning alchemy? Well, I would start by making a list of alchemists whose work I should read. Then, I would do a lot of reading. That might seem unimaginative – and it is – but, for centuries, that’s how people learned alchemy. Of course, they would eventually go to their laboratories or kitchens and try things out in practice. But reading was essential. So, it was a break with tradition when alchemist Isabella Cortese wrote in her book that

‘If you wish to follow the alchemical art, and practise it, you must stop studying the works of Geber, Ramon [Lull], Arnaldo [de Villanova], and other philosophers, because they said nothing truthful in their works except through images and puzzles.’

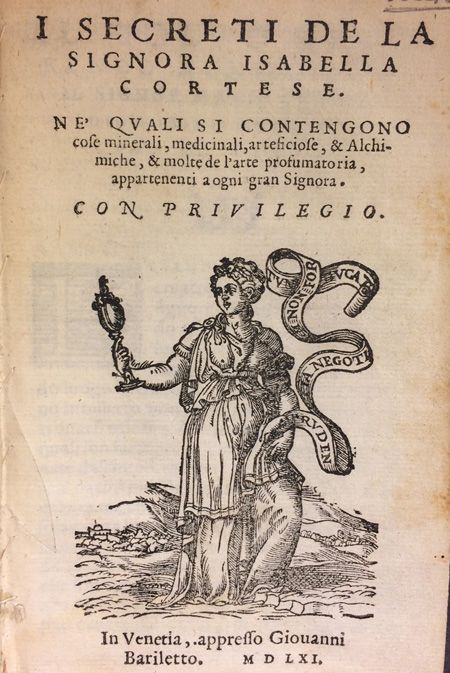

But let’s back up a bit. Who was Isabella Cortese? Well, the short answer is… We don’t know. Not really, anyway. One of the best-selling recipe books of the early modern period was attributed to her, but it is (very) likely that she was a fictitious character created by the publisher Giovanni Bariletto. In her book, Cortese described herself as a noblewoman who spent decades travelling and studying alchemy, gathering the recipes (‘secrets’) published in the collection. She argued against book learning: alchemy had to be learnt in practice. And that could be done at home: women should embrace ‘kitchen alchemy’.

Unfortunately, we have few clues about her besides what’s written in her book. Trust me, I’ve been looking for her in archives and libraries for almost a decade now, which is why I am convinced she was an invention. Yet, she was clearly inspired by great women alchemists of her day, such as Caterina Sforza and Isabella d’Este (might her name come from this Isabella?). It’s also intriguing that her last name, Cortese, is an anagram for ‘secreto’ in Italian. But ‘cortese’ also evokes nobility and wealth – it literally translates as ‘courtly’. Furthermore, the recipes were addressed to ‘every great lady’, highlighting how the work was gendered.

The book itself contained medical, alchemical, cosmetic, and veterinary recipes. In the early modern period, there was much overlap between these spheres, and books like Cortese’s had recipes for virtually anything. It might seem striking to us that formulas to treat baldness or remove stains from clothes appeared side by side with ways to prolong life (the elixir famously known as the ‘philosopher’s stone’) or to turn base metals into gold. Yet that was typical of recipe books of this period: what connected the recipes was the focus on practical instructions rather than theoretical explanations. Cortese was interested in how to make phenomena occur, not so much ‘why’ they happened.

Her collection also included many recipes about reproduction and the female body, such as advice on pregnancy and menstruation, hinting again at a female readership. Among the hundreds of recipes, there were many cosmetic formulas, which were chiefly prepared and used by women, even queens such as Elizabeth I. This is a typical entry:

Beauty Water for the Face: Take lemons and dried beans and combine them in white wine; add honey, egg, and goat’s milk, and distil it all together; and this water will make the face beautiful.

These recipes could be produced at home, in a domestic alchemical laboratory – in other words, a well-equipped kitchen. Therefore, this unique recipe book was doubly gendered: it was attributed to a woman and addressed to female readers. And what did Cortese tell them?

Cortese urged readers to stop reading the great alchemical masters of the past. Who should aspirant alchemists follow, then? As she wrote in the book’s dedication to her brother:

I ask you [dearest brother] not to waste your time with these books by philosophers but follow what I write for you, and do not omit or diminish anything, but do instead what I tell you and write [for you], and follow my instructions below.

Cortese’s brother – and her readers – were not to deviate from her orders. So, if at a first glance it may seem that Cortese is breaking with tradition by suggesting that alchemical adepts experiment by themselves, a more attentive reading shows that she is replacing one kind of authority with another: study gave place to experience. Instead of great men, who taught through theory, readers should follow great ladies, such as herself, who would teach them through practice. Her ‘new alchemy’ was an everyday pursuit open to everyone, regardless of their sex. Cortese invited lay women to directly engage in alchemy as her apprentices: ‘every great lady’ could be an alchemist, from their own kitchen.

References:

Isabella Cortese, I Secreti della Signora Isabella Cortese (Venice: 1565).

Further Reading:

William Eamon, Science and the Secrets of Nature: Books of Secrets in Medieval and Early Modern Culture (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994).

Meredith Ray, Daughters of Alchemy: Women and Scientific Culture in Early Modern Italy (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 2010).