A few days before Queen Elizabeth II’s death, she met the UK’s new prime minister, Liz Truss, at Balmoral Castle, in Scotland. Royal watchers were quick to point out what appeared to be a bluish bruise on her hand, as concerns over her health grew. At the time of her death, the Queen (1926-2022) was 96 years old, having reigned for 70 years. As the media coverage of the mourning and funeral rites took over the UK and much of the world, I couldn’t stop thinking about the Queen’s hands and ageing. I inevitably thought of Elizabeth I’s hands, famously beautiful with their long fingers, even into her old age. Although Elizabeth I (1533-1603) lived a much shorter life, during her 45-year reign her age was a matter of concern, for herself and others, especially as it became apparent that she wouldn’t marry and produce an heir. How did her gender shape the experience of growing old, and how did she deal with it? Most importantly, what does that tell us about our own feelings about the passage of time and our own mortality?

First things first: what exactly is to be ‘of old age’? Although Elizabeth II lived for almost three decades longer than Elizabeth I, both were perceived as elderly by their contemporaries. Naturally, life expectancy has changed from one Elizabethan age to another. Interestingly, in both cases, women tend to live longer than men. And, just like today, wealth and privilege played a big part in people’s health, not only because of access to healthcare providers but, crucially, to good nutrition and good living conditions in general.

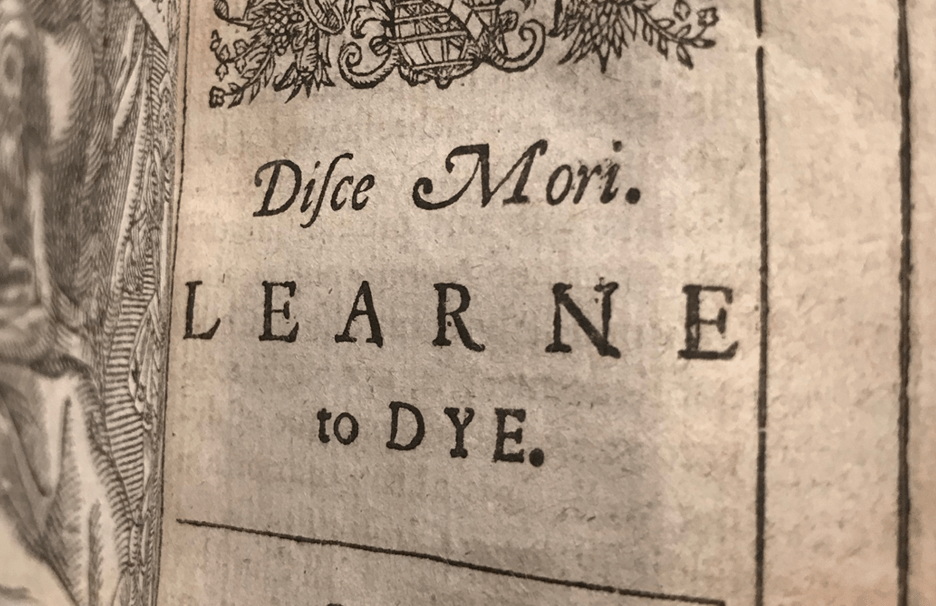

In Tudor times, a person’s life was divided into seven phases, each one composed of roughly seven years. Shakespeare described the ‘seven ages of man’ as infancy, school years, youth, maturity, middle-age, old-age, and dotage/death. For women who had escaped disease and survived childbirth, the sixth and seven ages were considered ‘old’.

Menopause often marked the beginning of this period (sorry for the pun!), with most medical writers describing it as something that happened between 44 and 58 years of age, a considerable window. With the cessation of menstruation, not only did fertility leave women but also the perception of youth and often beauty, as the later Lady Mary Wortley Montagu wrote:

Ladys here [are] so ready to make proofs of their Youth (which is necessary in order to be a receiv’d Beauty […]) that they do not content themselves with using the natural means, but fly to all sort of Quackerys to avoid the Scandall of being past Child bearing..

It is often said that beauty standards change with time: think of Marilyn Monroe’s voluptuous figure followed by Kate Moss’ slim silhouette and back to the curvaceous ideal represented by the Kardashians. Different traits can be beautiful, across time and space. Yet many cultures tend to associate beauty with youth, making it a fleeting ideal. The Tudors were no exception: ideals of beauty included golden hair, a high forehead, smooth and white skin, and youth. Beyond the racial implications of these standards, it is also fair to say that this ideal could be more easily attained by wealthier people, who would not labour under the sun and had access to expensive ingredients to produce cosmetics. White and slender hands were considered particularly attractive – the paleness another reminder of a privileged life indoors.

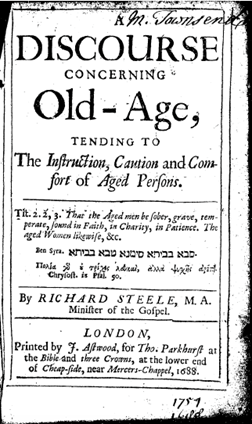

Sixteenth and seventeenth-century recipe books were full of recipes promising to make one beautiful and young. In Gervase Markham’s 1615 The English Housewife, a domestic guide comprising medical formulas and recipes for preserving food, readers could find this entry ‘to make smooth hands’:

To make an oil which shall make the skin of the hands very smooth, take almonds and beat them to oil, then take whole cloves and put them both together into a glass, and set it in the sun five or six days; then strain it, and with the same anoint your hands every night when you go to bed, and otherwise as you have convenient leisure.

Many of us still use almond oil to moisturise the skin, just like early modern people did. This recipe was not too expensive to produce; similar formulas included egg white and other ingredients that most people would be able to afford. But Elizabeth I was not an average person. Not only did she have access to very costly ingredients, but her ageing (and indeed her body) was a matter of public interest.

Elizabeth I was described as handsome when she was young, but also as vain and proud, especially as she grew older. She famously didn’t allow any mirrors in her rooms and made artists destroy paintings of her when she wasn’t pleased with the result. As her red hair turned grey, Elizabeth I covered it with wigs. Like many of her contemporaries, she lost many teeth, which was a source of distress for her. After contracting smallpox in 1562, Elizabeth I started to use make-up to cover the marks and scars on her face. This was a highly toxic formula containing white lead and vinegar, known as ‘ceruse’. Ironically, while it initially improved the skin’s appearance, it ultimately damaged it, creating even more wrinkles.

The use of cosmetics by elite and middling-sort women at the time was widespread. Yet many contemporaries saw make-up as a way to deceive others and defy God, especially in a society in which old women, often referred to as ‘crones’ or ‘hags’, were viewed with suspicion. As Elizabeth I grew older, she managed to fashion her image to become increasingly associated with perpetual virginity and ageless political power that transcended age and gender (as the moniker Gloriana illustrates). Dressed in armour addressing her troops before the famous victory against the Spanish Armada, Elizabeth I famously said she had the ‘body but of a weak and feeble woman’ – and an older one at that – but this body contained ‘the heart and stomach of a king’. Still, she was reluctant to name a successor or even acknowledge her own mortality, in the same way that her father, Henry VIII, did.

Growing old, in the case of female leaders such as Elizabeth I and Elizabeth II, is a fraught process. Although widely respected, both had to face many obstacles to consolidate their authority, with the main one arguably being their sex. As they approached old age, these queens dealt with their bodily changes differently – Elizabeth II didn’t use toxic lead-based cosmetics, for a start! Still, ageing queens arguably have an additional layer of difficulty in maintaining their power, through the way women were (and are) perceived. While Elizabeth I never had children, effectively ending the Tudor dynasty, Elizabeth II had four children and multiple grandchildren and great-grandchildren, assuring the continuity of the Windsor line.

And yet, Elizabeth II made headlines when she refused a wheelchair for her Jubilee celebrations; she reluctantly consented to use a walking stick for her engagements in the last months of her life. But would anyone judge a 96-year-old for having mobility issues? It seems that the Queen thought so. Going beyond individual personality traits both monarchs may have held, it is also fair to say that, as women, consolidating their power and authority involved the construction of a strong persona, transcending age and sex.

In some way, we all struggle with our mortality. But for both Elizabeth I and Elizabeth II, doing so in the public eye while trying to hold on to an image of power and strength must have been unimaginably difficult. Still, although her youth and beauty faded, I hope Elizabeth I could take comfort in her beautiful and slender hands, with their impossibly long fingers. Seeing the two queens’ coronation gloves side by side is a reminder of how much hasn’t changed from one Elizabethan age to another, for better or for worse.

References:

Gervase Markham, The English Housewife, ed. by Michael Best (Quebec: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1986). (First edition published in London in 1615.)

Thomas Tuke, A Discourse Against Painting and Tincturing of Women (London: Edward Marchant, 1616).

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, Selected Letters, ed. by Isobel Grundy (London: Penguin, 1997).

Pseudo-Albertus Magnus, Women’s Secrets, ed. by Helen Lemay (New York: State University of New York, 1992). (First edition De Secretis mulierum published in Leipzig in 1502.)

Further Reading:

David Cressy, Birth, Marriage and Death: Ritual, Religion, and the Life-Cycle in Tudor and Stuart England (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999).

Lisa Hilton, Elizabeth: Renaissance Prince (London: Hachette, 2014).

Elizabeth Norton, The Lives of Tudor Women (London: Head of Zeus, 2016).