CW: “Historical discussion of sexual coercion, blood & bodily harm”

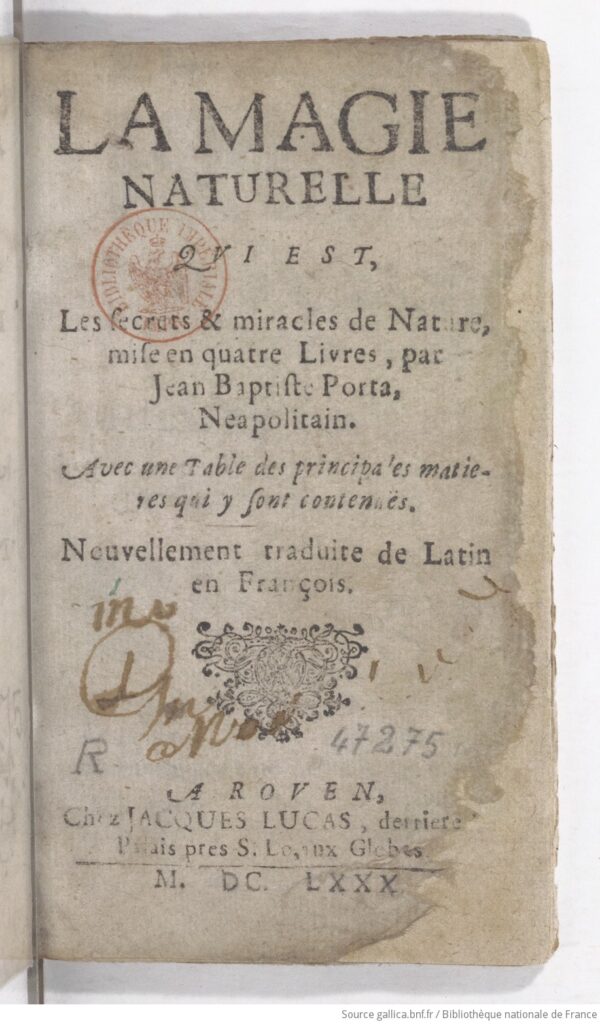

In Renaissance Europe, failing to bleed on your wedding night could cost a woman her dowry, her marriage – even her safety. So, of course, someone offered a solution. A 17th-century English translation of an Italian book called Magia Naturalis puts it like this:

“Make little Pills… and lay them on the mouth of the matrix [womb]… it will [lie] here and there make little bladders; which being touched, will bleed much blood, that she can hardly be known from a Maid.”

In case that wasn’t clear: the pills were meant to create blisters inside the vagina, so they’d rupture and bleed during sex. And this wasn’t hidden away in a secret manuscript. This recipe was printed, translated, and sold across Europe – in a popular book on natural magic. And that was just one method among many.

In this text, I’ll show you four methods mentioned in Magia Naturalis to “make a woman a virgin again” – including leech-induced scabs, dried pigeon’s blood, and a paint made from boiled lead. (Please don’t ever try this at home, I beg you!)

Chapter One – Virginity: Proof, Property, Problem

Let’s be clear: in the early modern period, virginity wasn’t just a moral ideal. It was legal, financial, and deeply public. In England, church courts were flooded with testimonies accusing women of being “spoiled,” “used,” or “not pure as she claimed.” And in much of Europe, a woman’s virginity was treated like a down payment on her dowry – proof that the goods hadn’t been tampered with. A stable marriage, it appears, wasn’t just sealed with a contract; it could demand the visual proof of bridal blood.

Of course, that created a problem. Virginity isn’t exactly a visible condition. It can be an ellusive concept. Even if we’re thinking about the hymen which, historically, people believed could can tear in all sorts of ways – horse riding, bicycles, dancing, or just existing in a world with stairs. Or it can be surprisingly resistant and flexible. Plus, some girls are just born without one. Not all bodies are the same. Still, for Renaissance women, virginity was socially important, it concerned their social status, their family and the community. Virginity could be seen as a guarantee that any children born after the wedding were legitimate.

In his book a Directory for Midwives, the medical writer Nicholas Culpeper stated: “bleeding is an undoubted sign of virginity”. In another book, The Fourth Book of Practical Physick, he went further: “…there is an alteration at first in Virgins, which causeth pain and bleeding, which is a sign of Virginity”.

So, for many early modern men, there was little nuance. They wanted blood. On the wedding night. On the sheet. And if there wasn’t any? Well, that could trigger a financial dispute, a public shaming, or an annulment. In some cases, the woman’s family might have to return the entire dowry. In others, the bride might be quietly sent back as “damaged goods”. This is what Renaissance people meant by a “bad match.” This went far beyond just sex. We’re talking family honour, fortunes, the integrity of inheritance, and the undeniable legitimacy of heirs.

And if a man really wanted to peek behind the curtain of a woman’s past? He’d look into the best-selling advice books of the age. Titles like Alessio Piemontese’s Secreti or Leonardo Fioravanti’s Specchio di Scientia Universale flew off the shelves, promising not just household remedies and marital peace, but also, more insidiously, the coveted ‘tests’ to check if a woman was ‘corrupted’. Yes, people were buying self-help books to diagnose virginity. Centuries before WebMD, and somehow even less reliable.

So what did you do if you didn’t bleed on your wedding night? This is where the pills made their agonising entrance – a promise of blood, brewed from pain and poison, yet offering a strange path to social redemption. Up next: the Renaissance’s most horrifying how-to guide.

Chapter Two – The Recipe: Four Ways to Fake It

So. You’re a Renaissance bride. Not exactly a virgin. And your entire future may hinge on bleeding convincingly. Giambattista Della Porta has some ideas. His 1558 Magia Naturalis, translated into English in 1658, offers four methods. Four. Because nothing says “I’ve thought this through” like an entire subsection on simulated defloration.

Here’s the first:

“A woman deflowred made a virgin again. Make little Pills thus: Of burnt Allome, Mastick, with a little Vitriol and Orpiment: make them into very fine Powder, that you can scarce feel them: when you have made them Pills with Rain-water, press them close with your fingers; and let them dry, being pressed thin, and lay them on the Mouth of the Matrix [the womb], where it was first broken open…”

Apply. Wait. Change every six hours. (Orpiment is arsenic sulphide, by the way, which is highly toxic.) Then:

“…it will [lie] here and there make little Bladders; which being touched, will bleed much blood, that she can hardly be known from a Maid.”

The goal was to create small, controlled wounds that would rupture during sex – a performance of purity, achieved through pain. Honestly, it’s less a remedy than a stunt. Bleed on cue, or else.

The second method?

“Midwives that take care of this, do it another way. They contract the place with the Decoction of the forementioned things, then they set a Leech fast on upon the place, and so they make a crusty matter or scab; which being rub’d will bleed.”

Leeches. Of course.

Imagine the trust required – not just in the midwife, but in the timing for this to work. (Having said that, I have my doubts that midwives would actually do this.) Here’s the third method:

“Others, when they have straightned the part, inject the dried Blood of a Hare or Pigeon; which being moystned by the moysture of the Matrix [the womb], shews like live fresh Blood.”

The idea was simple: insert the dried blood, let the body’s moisture revive it, and hope it looked convincing. And finally, Della Porta’s proudest contribution:

“I found out this noble way: I powder Litharge very finely, and boyl it in Vinegar, till the Vinegar be thick; I strain out that, and put in more, till that be coloured also: then I exhale the Vinegar at an easie fire, and resolve it into smoak.”

In other words: boil lead in vinegar until it becomes a thick, reddish paste. Apply as needed. Dangerous? Certainly. Effective? I have my doubts. As for “noble”? Only if you have a very warped idea of virtue. Taken together, the message is clear: your honour is your blood. And if you can’t provide the real thing, Della Porta will help you fake it. With arsenic. Or leeches. Or lead.

Now, none of this was new in the 16th century. Trota of Salerno, a medieval physician, had penned a recipe book with many ways of “restoring lost virginity”, too. Her work was widely read, and I think Della Porta was very familiar with her writing. Still, although one of her nine methods did use leeches, and another one even powdered glass, the other recipes were much less scary, using ingredients such as blackberry juice. But more on her on another text.

What is clear is that, in this culture, female honour was intimately bound to women’s perceived purity. It is very likely that writers such as Della Porta took inspiration from Trota’s work. But was this some cunning act of female agency? If you define agency as ‘choosing your preferred method of painful deception,’ then maybe. But it’s an agency exercised in service of inspection, a tactical submission to the gaze that demands proof. It’s a way of surviving in a patriarchal world.

“Virginity restoration”, perhaps unsurprisingly, has a long history, and recipes included everything from the ones I just mentioned to “tightening” formulas of all kinds and many other methods. And, by the 16th century, these weren’t secrets whispered in dark corners. They were published, translated, bought, and read. Next: how the same book told four very different stories across Europe.

Chapter Three – Scandal Across Borders: Translating (and Taming) Magia Naturalis

Now, you might think: surely this recipe caused some controversy. You would be correct. And this wasn’t even Della Porta’s most infamous formula. That would be the “witches’ ointment”, and I’ll probably make a video about that, too. I mean, who can resist talking about witchcraft, hallucinogenic formulas, aphrodisiacs, and flying off to orgies with the devil? I know I can’t.

As the name of the book indicates, Magia Naturalis was a book on natural magic, and the belief that nature was full of hidden forces that could be exploited and manipulated by humans to fulfill their goals. This was an area at the centre of a big political and religious controversy in the 16th century, and natural magic could be perceived as dangerously close to demonic magic. Ways of “faking virginity” definitely didn’t help.

So, as you’d expect, Della Porta’s Magia Naturalis had barely landed in print before people started panicking – not just about the bleeding pills, but about many of the “secrets of women” scattered through the book. Recipes to simulate virginity. Abort pregnancies. Seduce someone. Avoid seduction. Poison a man, or turn him into a leper. It was a one-stop shop for everything your local confessor would rather you didn’t know. Still, this was a book written in Latin for educated readers, and most people wouldn’t have been able to read it, even if they knew how to read in their local vernacular language.

But this would soon change. The first vernacular translation – in this case, Italian – printed in Venice in 1560, quietly deleted the virginity recipes. Along with the love charms. And anything involving poisons, wombs, or vaguely female agency. The witches’ ointment was heavily censored, too. The justification? That such things might be used by “evil people to do evil things.” Which, to be fair, does describe most of these recipes quite efficiently.

But let’s be honest: the concern wasn’t just about arsenic or alum. It was about access to knowledge. And a very sensitive kind of knowledge. Latin, the language of the original book, was for scholars. Reasonable people with discernment. But this was a time when literacy was quickly spreading, especially in the Italian peninsula. And so, vernacular translations, on the other hand, meant servants, wives, unmarried daughters – people who were meant to beread to – could have access to highly problematic information. The Church was not impressed by the idea that the general public would be able to read for themselves about how to manufacture the all-important signs of maidenhood.

Enter the Inquisition. After controversies surrounding recipes like the witches’ flying ointment I just mentioned, the Magia was tainted – not literally this time, just reputationally. By 1583, the book had been added to the Spanish Index Prohibitorum, the list of forbidden books. As for translators, they either purged it entirely or made editorial choices that, let’s say, prioritised sales over scandal.

Take France. In 1581, the French translation kept a recipe to test a woman’s chastity using a magnet, which the husband should place underneath her pillow without her knowing. If she was a virgin, she’d embrace her husband sweetly in her sleep. If not?

“She will be thrown away from the bed as if by a violent hand.”

Charming. And puzzling. But despite that flair for spectacle, they cut the flying ointment from the translation. Apparently, bodily illusions were marketable. Flying witches, less so. Meanwhile, in England and German areas – conveniently beyond the Pope’s reach – things went the other way. The 1658 English edition restored the whole bloody recipe catalogue. So did the 1677 German version, translated by Christian Knorr von Rosenroth, who even defended Della Porta by name.

So, depending on where you were, Magia Naturalis was either a respectable natural philosophy text… or a DIY guide to reproductive deception and much else. Same author. But not the same book. Depending on the language — Italian, French, English, or German — you’d find a totally different version: censored, sensationalised, restored, or quietly redacted. Even Della Porta himself, in the 1589 expanded version of the book, went ahead and censored his own text. He had faced the Inquisition twice, and he had definitely learnt from the experience.

Still, these “Italian ways of restoring virginity” caught the popular imagination. In a 1683 story, called “The London Jilt or, the politick whore”, a character even describes her days working as a prostitute saying that she had sold her virginity “the first time” and then she clarifies: “…Be not amazed, O reader, that I say the first time, for I have lost it several times after the manner of Italy”.

Which leaves us with one final question: why does this still matter?

Conclusion – Why a 400-Year-Old Pill Still Matters

It would be easy to file all of this under “weird things the Renaissance people did.” But the truth is, these recipes – and the fear that made them useful – never really went away. What Della Porta’s blistering pills reveal is a world obsessed with proof and performance. Not of love. Not of safety. But purity symbolised by blood.

And if you couldn’t bleed on cue, you could resort to improvising. Today, virginity still gets treated like evidence by some people. From online myths about “testing purity” with garlic, to actual clinics offering hymen repair surgery – the obsession lingers. The core fear of female sexuality persists, simply repackaged for our times. We talk about progress. But there are still girls all around the world facing exams, accusations, even violence, all because someone believes virginity can – and should – be proven.

History doesn’t repeat itself. But it does recycle the bad ideas. Especially the ones that blame women. So, next time someone says “the past was simpler,” you can remind them: Renaissance bestsellers openly taught women to bleed on command, because in their world, the price of failing that one, bloody ‘purity’ test was infinitely more terrifying than any poisonous recipe could be. What a scary thought that is.

If you enjoyed this text, bleak as it was, please consider becoming a Patron on Patreon, it really does help. Thank you, and see you next time!

References:

Laura Balbiani, La Magia Naturalis di G. B. Della Porta (1999).

Antonio Corsano, Per la storia del pensiero del tardo Rinascimento (2002).

Nicholas Culpeper, A Directory for Midwives (1662).

Giambattista Della Porta, Magiae naturalis, sive de miraculis rerum naturalium (1558).

_________, De i miracoli et maravigliosi effetti da la natura prodotti (1560).

_________, Magiae naturalis, sive de miraculis rerum naturalium (1589).

_________, Natural Magick (1658).

_________, Magie Naturelle (1581).

_________, Des vortrefflichen Herrn Johann Baptista Portae von Neapolis Magia Naturalis, Oder: Hauß-, Kunst- und Wunder-Buch (1680).

_________, De i miracoli et maravigliosi effetti da la natura prodotti (1677).

William Eamon, Science and the Secrets of Nature (1994).

_________, Natural Magic and Utopia in the Cinquecento: Campanella, the Della Porta circle, and the Revolt of Calabria, Memorie Dominicane (26), 1995.

The Trotula: A Medieval Compendium of Women’s Medicine, (trans. and ed. by Monica Green) (2001).

Rudolf Hirsch, The Printed Word: Its Impact and Diffusion (1978).

Helen King, Immaculate Forms: Uncovering the History of Women’s Bodies (2025).

Daniel Sennertus, Nicholas Culpeper, and Abdiah Cole, Practical Physick: The Fourth Book in Three Parts (1664).

Sophia Smith Galer, The sex myth that’s centuries old, BBC Future (April 2022).

Maurizio Torrini (ed.), Giovan Battista Della Porta nell’Europa del suo tempo (1990).