CONTENT WARNING

Discussion of bodily harm and eating disorders.

Social media might make it seem like fasting (and especially intermittent fasting) is something new. But fasting – voluntary or not – has arguably existed for as long as humans have. People have abstained from food throughout history for many different reasons, not least of which scarcity of nourishment (think of hunter-gatherers during a harsh winter). But the main reason for voluntarily fasting has been religion – just think of the Islamic Ramadan or the Christian Lent. An extreme version of religious fasting has been called ‘holy anorexia’ (anorexia mirabilis), and it was not a rare occurrence among medieval saintly women. The most famous example is perhaps St Catherine of Siena (d. 1380), who died from the rigorous practice. Her ecstatic visions were often centred around food and starvation as a way of embodying her love for Christ. She was known for eating nothing but the holy wafer (the eucharist), despite the pleas of her religious community, including her confessor. But where did this trend come from? And why was it much more prevalent among female saints?

The term ‘anorexia’ comes from the Greek an (lack of) and orexia (appetite), encompassing a range of practices with various meanings. For medieval Christians, abstaining from bodily pleasures to achieve a higher spirituality was considered a noble goal; many religious orders took poverty vows, and by the 12th century, celibacy had become a universal requirement for priests. Religious fasting could bring people closer to God, and conversely, gluttony was considered sinful. Moreover, in a period in which food was not as plentiful as it is today, indulging in the sensual pleasure of overeating was often frowned upon, whereas refusing to eat for religious reasons was praised. Fasting became increasingly revered from the 13th century on, with the beginning of this trend perhaps best illustrated by an episode in which Christ appeared to St Margaret of Cortona (d. 1297) in a vision, telling her that ‘Christians cannot be perfect unless they restrain their appetites from vices, for without abstinence from food and drink, the war of the flesh will never end’.

‘Holy anorexia’ was a social, religious, and psychological phenomenon, which reached its peak in the 15th century, when hundreds of saintly women were recorded as having survived on little or no food, according to some contemporary writers. Most cases were recorded in the Italian peninsula, with plenty of examples both before and after that period (you can check out a wonderful summary in pictures here); still, the 15th-century numbers the most cases of anorectic mystics. Because so many women in this period undertook extreme fasting, some historians have likened their anorexia mirabilis to the contemporary anorexia nervosa. But we should be careful with anachronisms: medieval people understood their bodies in a very different way than 21st-century people do. Yet many of these saints are still revered by Catholics today, as a symbol of piety and devotion.

For religious women, food was one of the few ways in which they could control the world around them; through renouncing ordinary food, they turned themselves to the divine nourishment of Christ. By embracing the suffering of the passion and letting go of their physicality, saintly women could paradoxically control their bodies. They could get closer to the divine, understand the pain of Christ, and elevate themselves above the people around them. Significantly, with excessive weight loss, many of these women stopped menstruating (amenorrhoea) and, while the primary goal of fasting was not reducing fertility, it was an unintended consequence. For religious, unmarried women, this may not have directly impacted their lives: they weren’t meant to become pregnant anyway. Still, in a period in which motherhood was almost synonymous with womanhood, this ‘un-sexing’ could arguably help them transcend the constraints of the human body and matter itself, illustrating medieval asceticism’s focus on the immortal soul.

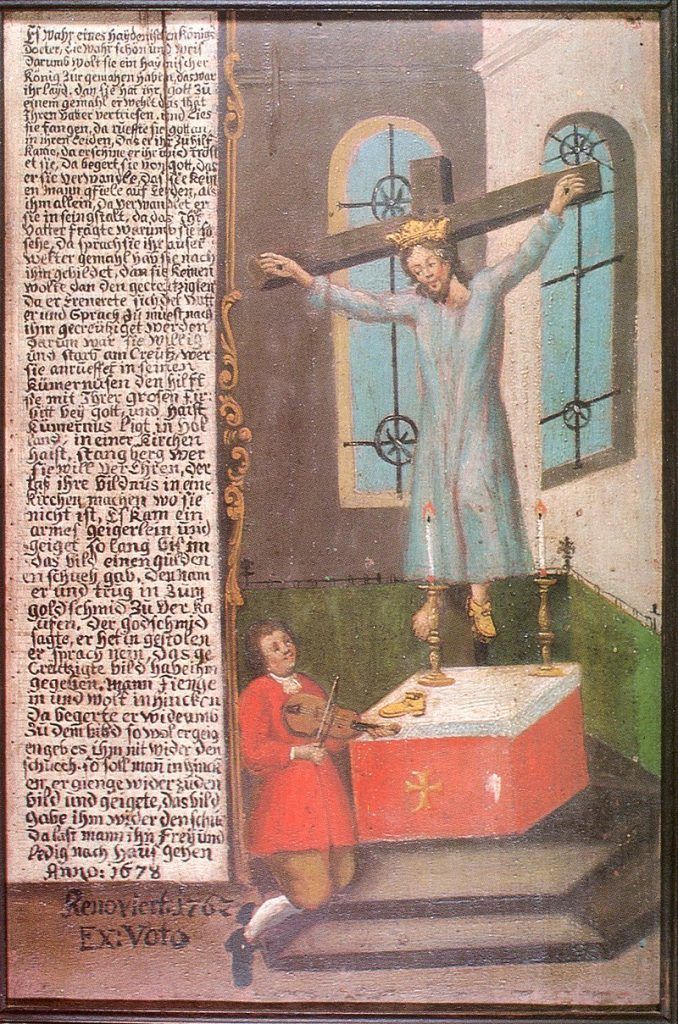

It is not a coincidence that other religious women of the period, such as Joan of Arc, were known both for not menstruating and for arduous fasting (You can read more about blood and ‘un-sexing’ here.) Transcending the body (and especially the female body) through self-starvation was even more apparent in the case of St Liberata, also known as Wilgefortis (from virgo fortis, strong virgin). Her extreme fasting resulted in the development of facial hair (lanugo), and she has been adopted by some in the queer community as a transgender saint. Her father, the king of Portugal, wished her to marry, while Wilgefortis intended to devote her life to Christ. The story goes that, through fasting, she stopped menstruating and grew a beard, making her less attractive to potential suitors. Her father had her crucified. Not surprisingly, this 14th-century story became the basis for Wilgefortis’ popular devotion for more than two centuries, during the height of ‘holy anorexia’.

Still, the question remains: why was this more widespread among religious women? Fasting wasn’t exclusive to women, but there are far fewer male saints remembered for anorexia mirabilis. Cultures of piety varied across time and place, but female religiosity was perhaps best illustrated through the relationship to food. For religious men, on the other hand, it was giving up power, wealth, and sex that constituted the main path to the divine, through chastity and poverty. Women and men chose different symbols with which to express their devotion to Christ, depending on religious doctrine as well as expected societal gender roles. In patriarchal Catholicism, men were dominant: renouncing this dominance was best illustrated by letting go of power over others (exemplified by sex and wealth). For women, it was renouncing their roles as wives and mothers that indicated a shift from the worldly to the divine. To do so, these female mystics adhered to strict ascetic practices, which included self-flagellation and interrupted sleep as well as extreme fasting, to experience Jesus’ bodily suffering on the cross: while they renounced their own bodies and sexuality, they identified with the body (and the humanity) of Christ.

Throughout the centuries, many saintly and mystical women became known for religious fasting. Notable examples, besides the ones mentioned above, include Elizabeth of Hungary (d. 1231), Clare of Assisi (d. 1253), Margery Kempe (d. 1438), and Teresa of Avila (1582). They were exceptional people: their practices were not typical of most religious women, let alone ordinary women. These saints were praised as models for others because of their incredible discipline, sacrifice, piety, and devotion. When reading the accounts of their lives, we should be careful not to impose contemporary diagnoses or labels on people who lived in the past. We should also question the sources that recount their miraculous feats.

Yet, regardless of the specific details surrounding someone like Catherine of Siena’s fasting, these stories give us a glimpse into what late medieval people found inspiring and admirable. They also hint at women’s responses to life under the socio-political constraints of medieval Catholicism, in which control over their bodies had to be negotiated. These tales highlight a human longing for a connection with the divine, which ‘holy anorectics’ sought to achieve by renouncing from food, which ultimately also symbolised their nurturing and maternal roles in a patriarchal society. Finally, ‘holy anorexia’ and fasting were framed as virtuous and, the people who practised them, as examples of piety. With so many social media influencers today extolling the benefits of fasting, it might be helpful to look back and question our reasons for adhering to these practices, and how that shapes the way we understand our own bodies.

References:

The Dialogue of the Seraphic Virgin, Catherine of Siena: Dictated by Her, While in a State of Ecstasy, to Her Secretaries, and Completed in the Year of Our Lord 1370; Together with an Account of Her Death by an Eye-Witness (London: K. Paul, Trench, Trübner, 1907).

Fra Giunta Bevegnati, The Life and Miracles of Saint Margaret of Cortona (1247–1297),(Bonaventure, NY: Franciscan Institute, 2012).

Further Reading:

Caroline Walker Bynum, Holy Feast and Holy Fast: The Religious Significance of Food to Medieval Women (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987).

Rudolph M. Bell, Holy Anorexia (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1985).

Ilse E. Friesen, The Female Crucifix: Images of St. Wilgefortis Since the Middle Ages (Waterloo, CA: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2001).