Content Warning: Childbirth pain and death

Giving birth in early modern Europe was a dangerous rite of passage, one which most women would go through, and some would not survive. Women were largely defined by their domestic roles as wives and mothers: going through childbirth often changed a woman’s social status, as matrons were usually more respected, in no doubt thanks to their lived experiences giving birth and caring for their families. Yet many women feared childbirth. Besides the promise of pain, the possibility of either or both mother and baby not surviving could be daunting, which made some expectant mothers write to their unborn children, in case they were never able to meet them.

The Social and Spiritual Complexities of Childbirth in Early Modern Europe

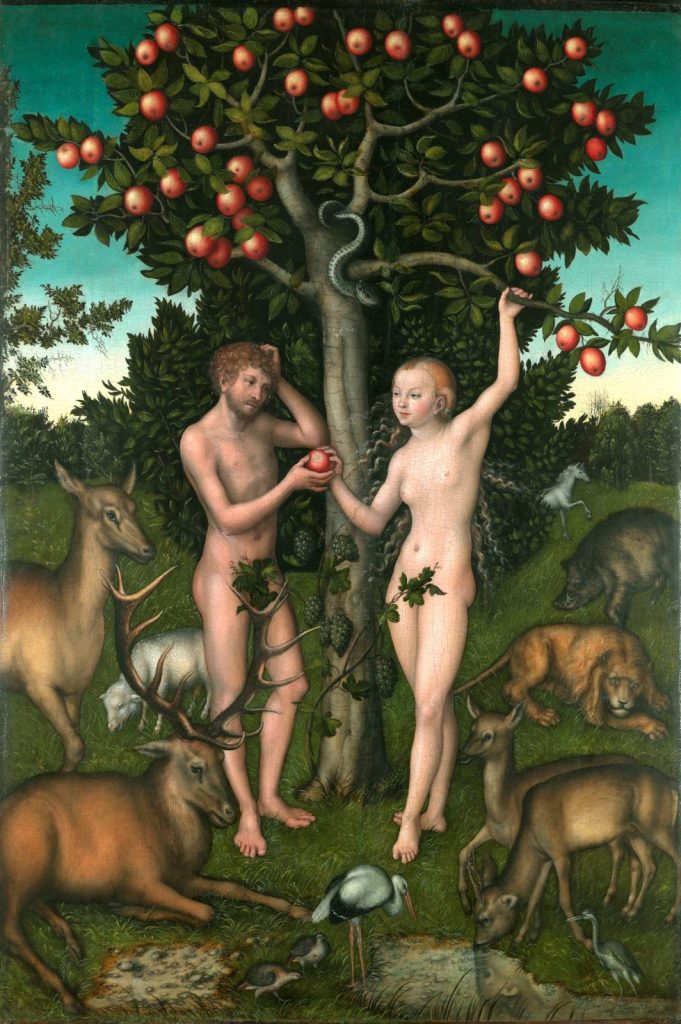

Those about to give birth would pray to be able to endure the suffering of childbirth and its unavoidable pain. According to the Bible, as daughters of Eve, all women were cursed with pain, to atone for the original sin:

‘I will greatly multiply your pain in childbirth; In pain, you will bring forth children’.

So, childbirth pain was more than natural and physiological: it was God-given. And, although midwives knew many ways of speeding the delivery and alleviating pain, many women would pray to be able to endure it and survive the birth. Elizabeth, Countess of Bridgewater (d. 1666), wrote down the prayer she would utter as her time approached:

‘Lord Jesus since thou art pleased my time is come, to bring forth this my babe, thou hast made in me, give me a heart full of all truth and obedience to thee and that I make take this height of pain patiently, without grudging at thy holy will and pleasure […] O Lord hear, O Lord forgive, and suffer me not to accompany my sins in the deep, but part us, and make me become a new creature, and if it be by thy will, O God, that I should be no more in this world, Christ raise me to life everlasting in the true belief of thee, who art my only saviour: Amen.’

Elizabeth asked for the strength to face the expected pain, but, knowing how perilous the journey was, she also asked to survive. For those interested in history, it is easy to find many examples of women dying in childbirth. Just think of Henry VIII’s wives: two of the six died following difficult deliveries, Jane Seymour and Catherine Parr, who by then was married to Thomas Seymour. Yet these famous cases might give us an inaccurate picture of early modern childbed deaths. Most women survived childbirth with few complications and recovered well.

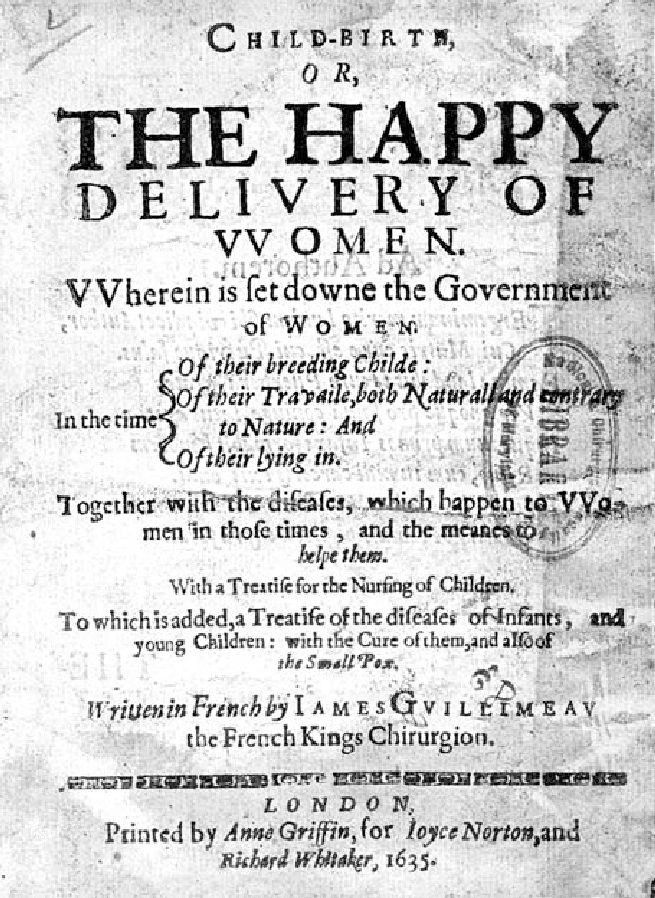

Famously, in the 1612 Child-Birth, or The Happy Deliverie of Women, Jacques Guillemeau wrote how of a thousand births, ‘there is scarce one found that is amiss’. That number was probably closer to 1% in Elizabethan and Jacobean England, but still, dying in childbirth was not as common as we tend to believe. (You can also watch a video in which I talk about statistics here.) However, that did not mean that women did not fear the perils of childbirth.

Maternal Letters and Prayers: A Legacy for the Unborn Child

It was not uncommon for expectant mothers to write wills as their time approached, as well as letters to their unborn children, in case they survived, and the mothers did not. That is exactly what happened to another Elizabeth, a Jacobean gentlewoman called Elizabeth Joceline (1595–1622), who died at 26 years old, nine days after giving birth to a daughter. The text she wrote before the delivery was published posthumously and called The Mothers Legacie to her Unborn Child. And it’s just heartbreaking.

Elizabeth wrote of her happiness at being pregnant; the book is joyful and full of advice for her unborn child. Elizabeth was clearly determined to be the best mother she could be. So, she advised the child to pray often, respect sacred days, be charitable, and avoid temptation. She was very much a woman of her time, and so, she also issued specific advice depending on gender: girls should be raised to be obedient and, eventually, good mothers – presumably, just like she had been. It was not necessary for them to learn much else, although that could be valuable – if they were virtuous:

‘I desire her bringing up may bee learning the Bible, as my sisters doe, good housewifery, writing, and good works: other learning a woman needs not; though I admire it in those whom God hath blest with descretion, yet I desired not much in my owne, having seene that sometimes women have greater portions of learning than wisdom […] But where learning and wisdom meet in a vertuous disposed woman she is the fittest closet for all goodnesse. She is like a well-balanced ship that may beare all her saile. […] I pray God give her a wise and religious heart, that she may use it to his glory, thy comfort, and her own salvation.”

Elizabeth goes on to say that, if the baby is a girl, her daughter might think that Elizabeth had died in vain delivering her, highlighting the usual preference in families for sons. Yet that was not the case:

‘…thou shalt see my love and care of thee [a girl] and thy salvation is as great, as if thou wert a sonne, and my feare greater”.

As a woman, Elizabeth understood what awaited her unborn daughter; she was full of empathy for her future daughter. The Mother’s Legacy allows us a glimpse into the intimate life and thoughts of an early modern mother-to-be. It is perhaps the best example of how conscious early modern women were of the perils of childbirth and how, despite that, many of them were able to feel joyful and hopeful.

This book was reprinted multiple times, well into the 19th century, and read by countless women. Once more, just like the Countess of Bridgewater’s private prayer, this text delineated a model of fortitude based on faith for all expectant mothers. Fulfilling the role expected of her by a patriarchal and Christian society, even after death, Elizabeth was an ideal early modern mother: she thought of her child and family above all else. It is particularly hard not to feel emotional when reading her advice to her husband about how to select a nurse to breastfeed their child in case Elizabeth died, especially because we know he needed to do so, just over a week after the birth.

References:

Jacques Guillemeau, Child-Birth, or The Happy Deliverie of Women (London, 1612).

Elizabeth Joceline, Mothers Legacie, to her Unborne Childe (London, 1624).

Further Reading:

David Cressy, Birth, Marriage & Death: Ritual, Religion, and the Life-Cycle in Tudor and Stuart England (Oxford, 1999).

Roger Schofield, ‘Did the Mothers Really Die? Three Centuries of Maternal Mortality in ”The World We Have Lost”’, in The World We Have Gained: Histories of Population and Social Structure, edited by L. Bonfield, R. Smith, and K. Wrightson (Oxford, 1986), pp. 231-60.