CONTENT WARNING:

Fatphobia

According to the UK’s National Health System, ‘Being overweight or obese’ is considered a risk factor for infertility. Pregnant people who are fat are often told about higher risks of complications during pregnancy and may have their birth choices limited due to their size. The fat acceptance movement have shown how fraught the relationship between health systems and fat, pregnant bodies can be, and how pervasive and harmful fat shaming is. Unfortunately, it is also an issue that overweight people have dealt with for millennia.

This negative stereotyping has its roots in Hippocrates (c. 460 BCE- c. 370 BCE), usually considered the ‘father of Western medicine’. For Hippocrates, slender women had more chances of conceiving than fat ones, as ‘to be very fleshy is evil’. Other ancient sources, such as Aristotle and Galen, understood fat bodies to be inherently less fertile than slim ones and were quoted, along with Hippocrates, until the 18th century.

In the 16th and 17th centuries, midwifery manuals, medical books and recipe collections aimed at a broad readership were published in vernacular languages, hoping to instruct readers on reproduction matters. In a best-selling book of the period, The Secrets of Don Alessio Piemontese, readers found entries such as ‘For women who cannot conceive due to fatness’, printed alongside ways to facilitate childbirth for bigger bodies. This advice was often about how fat women should ‘give birth on all fours, like beasts’. While we know much about how different birth positions can be helpful today, what is striking about this entry is the likening of fat women to animals.

However, early modern authors such as Alessio Piemontese did not simply repeat earlier prejudices about bigger bodies inherited from the Greek and Roman medical tradition. Fat bodies were seen as inherently disruptive, and therefore problematic, resisting gender expectations. Moreover, fatness could be seen as ‘unchristian’, as it testified to a lack of restraint and indulgence in the sin of gluttony. In popular print, fat bodies were linked to many reproduction problems. Overweight men were associated with impotence, lower sexual drive and were thought to produce seed (semen) of lower quality. Fat women were considered more likely to miscarry and to have difficult births. Because fat was supposed to be made of congealed blood, it could also disrupt a woman’s regular menstrual cycle, considered a pre-condition to conception.

In Nicholas Culpeper’s A Directory for Midwives, readers were told that fat women’s menstrual blood became fat, so their menstruation might cease, preventing conception. If conception did happen, there would likely not be enough blood to feed the growing foetus, as menstrual blood was thought to nourish the foetus in the womb throughout pregnancy. (That is why pregnant women would not normally menstruate.)Fat bodies were therefore thought to selfishly use up resources, which would then be lacking to generate a baby. According to Jane Sharp, in her Midwives Book, fat women were simply not ‘fit for child-bearing’.

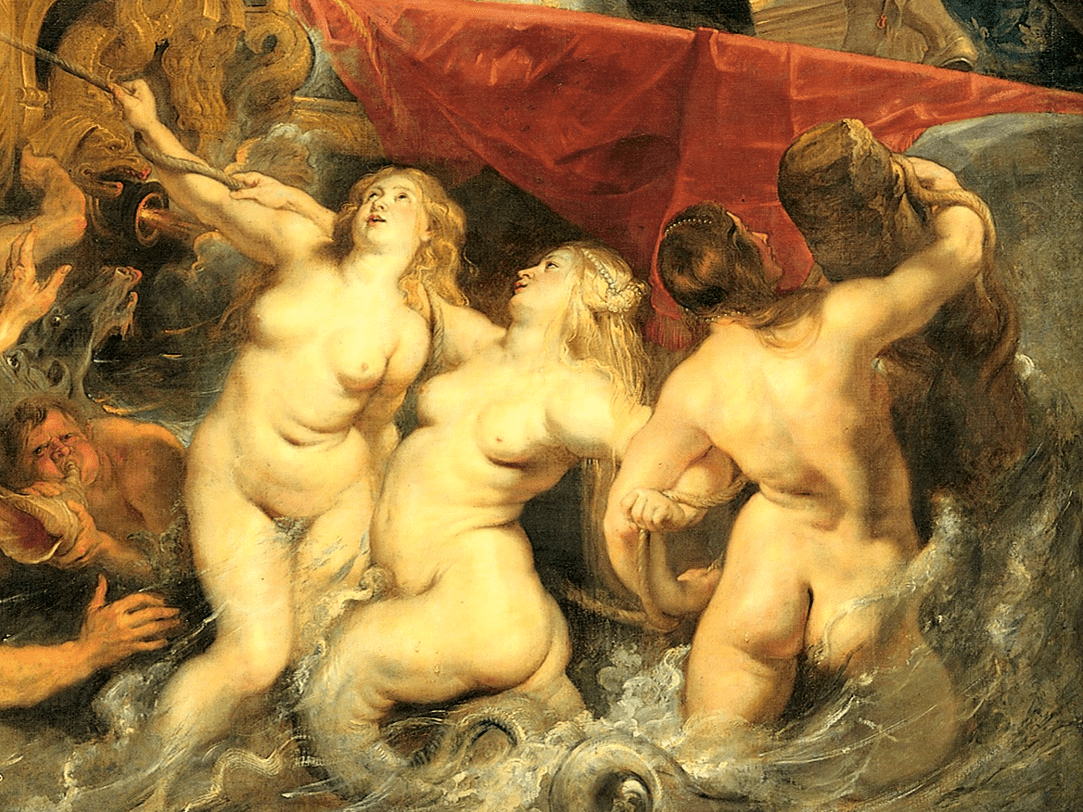

Fat bodies were seen as less suited to reproduction in general. Early modern understandings of the body linked desire (and desirability) to fertility, which meant that bodies considered less aesthetically pleasing were necessarily less able to fulfil their social roles. Paradoxically, Renaissance aesthetics usually considered plumpness attractive if it was not excessive. As always, perceptions of fatness and beauty were subjective. Plump women were generally thought to be healthy and fertile, while those who were too ‘gross’ (fat) were believed to be less so. When reproduction was the primary goal of matrimony, and motherhood, the main role women were expected to play, fat bodies were not only considered less virtuous, lacking in Christian moderation, but incompetent in fulfilling their primary social role for the stability of the community.

Of course, the preoccupation with generating offspring and securing the continuation of bloodlines was particularly significant for higher classes. These were also the ones more likely to be fat in the first place, leading less demanding lifestyles and being able to afford richer food (and more quantity of it). While class played an essential part in how fat bodies were seen, fatness was associated with moral corruption and reproductive issues in most social circles. In medical books, readers were advised about losing weight to facilitate conception, even though it was often assumed that fat people would be too indolent to follow them. If a lifestyle change did not help, changing sexual positions for intercourse might be useful – as it was thought that fatness prevented the penis from going deep enough into the vagina for the semen to reach its destination. Women could therefore be penetrated from behind, rather than the religiously approved face to face position with the man on top.

The pathologising of fat bodies is not a contemporary phenomenon. Negative attitudes towards fat bodies (especially feminine bodies) were primarily based on a perception that these disruptive bodies would not fulfil their expected gender roles. Female fat bodies were not maternal, selfishly eating up resources that should be used for a child and preventing the woman from fulfilling her primary social role. Significantly, this was thought to be self-induced, with fat people being blamed for their failure to reproduce. So, being a fat woman could be seen as subversive, rejecting the role society and religion had assigned to women. Today, fat bodies may be pathologised for different reasons. But they are still seen as inherently less healthy than ‘regular’ bodies – at least outside of fat activism circles. Maybe it is time to finally retire old associations of fatness with moral and social failings and embrace human diversity in all its forms.

References:

Jacques Jouanna, Hippocrates (London: 1999).

Alessio Piemontese, I Secreti del reverendo Donno Alessio Piemontese (Venice: 1557).

Nicholas Culpeper, A Directory for Midwives (London: 1651).

Jane Sharp, The Midwives Book (London: 1671).