Fairy tales don’t have to make sense to be meaningful. They follow their own logic and readers – or, traditionally, listeners – get so enraptured in the story that no one really questions their elements, be they fairy godmothers, magic roses, or talking frogs. Yet there is one story that always left me puzzled when I was growing up: The Princess and the Pea.

Was a ‘real princess’ really incapable of sleeping because of a hard pea underneath all the fluffy layers? What did that tell people about wealth, femininity, and being a ‘true’ princess, deserving of marrying the prince, instead of an ambitious commoner (not to say a potential con artist…)? What was the lesson people were being taught? These are all valid questions that folklorists, historians, and literary scholars have written about. But for me, the main one has always been where the idea of piling mattress on top of mattress came from. Did no one find that sleeping arrangement weird? Let’s swap Copenhagen for London. Let me take you to a couple of centuries back, before Andersen wrote this tale, and tell you about early modern beds, from their practical aspects to their symbolic meanings.

The Princess and the Pea

Hans Christian Andersen (1805-1875) first heard the tale of the princess and the pea as a child. It was probably a Swedish folktale, which he later wrote down and published in 1835. The story sets out with an anxious prince who needs to marry. But, alongside his mother, the queen, the prince worries about the many young women who could pretend to be of noble blood in the hope of marrying him. He needs to find a ‘real’ princess. One stormy night, they find a woman by the castle gate, soaked by the rain. She tells them she is a princess and asks for shelter in the castle.

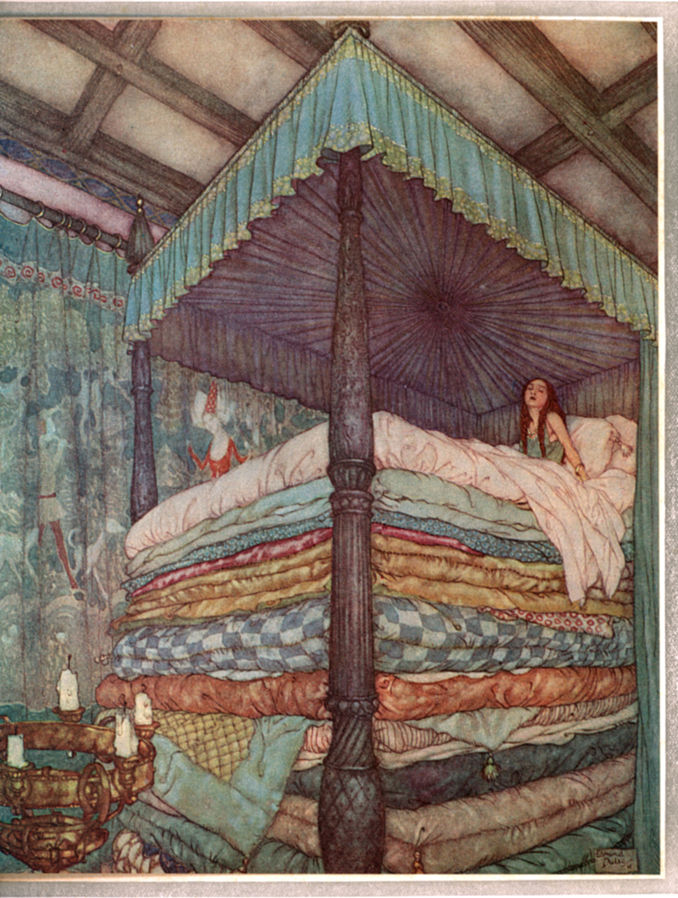

The suspicious mother decides to test her refinement and delicacy by placing a hard pea underneath a pile of twenty fluffy mattresses. In the morning, the girl tells the queen and the prince how she couldn’t sleep, since there was something hard underneath the mattresses, which injured her body. This persuades mother and son of her royal blood: only a ‘true’ princess could be so delicate as to be bothered by the hidden pea. The couple marries and the pea is eventually displayed for all to see in a museum – a testament to the young woman’s noble blood and the royals’ ingenuity.

Regardless of how you read the story – as a satire of nobility, as a reminder not to judge a book by its cover, as a tale of absurdity – it is telling that it was a bed that was chosen to showcase the difference between a pretender and someone who had grown up used to luxury and comfort.

The Hierarchy of Early Modern Beds

Let’s take Elizabethan England as an example. Beds could be extremely expensive; indeed, they were the items most often mentioned in wills and inventories of the period, besides money and landholdings. However, the way people slept varied greatly, depending on social status and wealth. At the very bottom (literally), there were those who just lay on the floor wherever they could. A little bit more comfort would involve piles of straw to soften the earthen floor (unfortunately, mice were eager to join in, which made this set-up less than ideal).

The next, literal, step-up would be sleeping on a sack of straw, possibly on a raised platform off the floor. This not only helped ward off vermin but was particularly useful in the draughty rooms of the time. Wooden box beds and rush mats were an improvement, as were rope-strung truckle beds. They were easy to produce and created a net with some bounce to it over which the mattress would go. These beds could be easily moved out of the way, underneath larger beds, which made it perfect for children or servants. Softer mattresses could be made of hay, flock, or wool. These were much more comfortable than straw, but harder to maintain well, which was why these mattresses were usually piled on top of a straw mattress, which would buffer the friction against the ropes.

Within these mattresses, people often added aromatic herbs, such as lavender. Just like today, it was believed that lavender would facilitate sleep. Wormwood and lady’s bedstraw, on the other hand, would help with any insects that tried disturbing your night’s sleep. But what should go on top of all of this? Well, bolsters, pillows, and blankets, along with linen pillowcases and sheets, would be very comfortable options. However, these were out of reach for most people. A prosperous couple might have pillowcases and sheets in their marital bed, but their children probably wouldn’t, nor any servants who might work in the house.

The next step up would include a feather bed (‘bed’ in this period often meant mattress). These were the most comfortable, not only the softest but also the warmest beds you could sleep in. The more feathers, and the smaller they were, the better. The down from eider ducks (‘eiderdown’) was widely believed to be the best option, which was reflected in its price. Once more, these feather beds were piled over a flock or hay mattress, which would be over a straw mattress. Significantly, all of these beds/mattresses could have been used as a cover or duvet on top of the person sleeping; if you had several ‘beds’ you could just sleep in between them. So, the more layers you had, the more comfortable you would be – and the tale of the Princess and the Pea is already sounding less strange!

A Luxurious Bed

So, what would the ‘ideal’ Elizabethan bed be like? Well, the pile of mattresses (rush mat, straw sack with herbs, flock bed and ideally two feather beds, with the best one on top) would go inside a wooden bed frame and over the tightly-strung ropes – which is where some people believe that the expression ‘sleep tight’ comes from, as it was important for the ropes to be pulled tight with a wooden peg for the bed to be comfortable and not sagging in the middle. (That’s probably not true, though.) Four-poster beds were highly prized, especially with a headboard and wooden ceilings, or at least a thick fabric top. Around the bed, heavy curtains and maybe decorative silks would be hung, making the bed a room within a room.

Remember, most houses didn’t have corridors, so people often had to pass through other rooms to access their own. Curtains around the bed afforded a couple privacy, but they also made sleeping cosy and warm. On top of the five layers of beds, there would be sheets of linen, pillows and bolsters of feathers, plus blankets and a coverlet, lined with furs and embroidered with precious materials. Although few people could sleep in a bed like this in the early 16th century (it could cost more than a small farm!), by the end of the century that was more likely, with a gradual increase in those who could afford it. (You can read about earlier, medieval beds here.)

Of course, for these beds to be truly luxurious, it was crucial to air the mattresses, brush the wool curtains, and most importantly, wash the linen. Early modern hygiene prioritised cleaning all fabrics that would touch the body, as excrements such as sweat would leave the skin pores and get trapped in the fabric. Moreover, washing sheets helped to prevent the spread of bed bugs, which shouldn’t be underestimated in this period. Still, as the century progressed, the sleeping standards of many improved, especially for craftsmen, yeomen and members of the lower gentry. Chimneys proliferated, as did glazed windows. Bedsteads became more common, as did woollen and feather beds. (You can read more about sleeping habits here.)

Beds as Symbols

Travellers such as William Harrison (1534-1593), wrote of the cleanliness of the English inns where they stayed, and especially the beds, with linen sheets ‘wherein no man hath lodged since they came from the laundress’. With the increase in travel at the time, some inns even used their beds as a way to attract visitors. The Great Bed of Ware became a tourist attraction, as it could fit more than ten people. Travellers could find it in the Hertfordshire town, where people would stop on their way from London to Cambridge. Most Elizabethan beds were 6 ft x 7ft in size; the Great Bed of Ware was 10.7 ft x 12 ft (!!!), and it was even mentioned by Shakespeare in Twelfth Night (1601) when Sir Toby Belch described a sheet of paper as “… big enough for the Bed of Ware!”. (By the way, you can still see this bed at the V&A, which I highly recommend you do!)

Naturally, beds such as these were extremely uncommon. But, as more and more people could afford to sleep in a comfortable bed, composed of several mattresses on top of each other, not only in England but in continental Europe too, those of noble birth could make their own beds even more luxurious, to signify their wealth and superior social class. This brings me back to The Princess and the Pea, written down centuries later. Perhaps the tale – and Andersen himself – was mocking the aristocracy and its need to be literally above the common folk, sleeping piled high over feather mattresses. In any case, it is clear that beds could be weaponised in the discourse about purity and refinement, and where people belonged: if you couldn’t feel a hard pea through the mattresses, maybe you shouldn’t aspire to marry a prince at all.

References:

William Harrison, Description Of Elizabethan England (1577).

John Taylor, In the Praise of Cleane Linnen. With the commendable use of the laundresse (London, 1624).

Thomas Tusser, A Hundreth Good Pointes of Husbandrie (London, 1557).

Further Reading:

Ruth Goodman, How to be a Tudor: A Dawn to Dusk Guide to Everyday Life (London, 2015).

Ian Mortimer, The Time Traveller’s Guide to Elizabethan England (London, 2012).

Lawrence Wright, Warm and Snug: The History of the Bed (Stroud, 2004).