Imagine that you’re a 16th-century person flicking through the pages of Alessio Piemontese’s best-selling book, which contained everything from how to make invisible ink to how to make strawberries preserve. And then you come across this most interesting ‘secret’:

An other remedie verie good, and well knowen of women. Take a sweet Apple, and make him hollow within, make a pouder of Nutmegs, Mace, Synamon, of each halfe a dragme, Cloves halfe a scruple: put all this within the Apple with a little Suger, and rost it under hote ashes, and give of it onto the woman ever when the paine commeth onto hir. But if the paine increase so much that hir life is in doubt, put to all this two graines of Opium, and sodainly the paine will depart.

But why would people try to stimulate menstruation? Well, in premodern Europe, the humoral theory was the main framework for understanding the body: the four humours (blood, black bile, yellow bile, and phlegm) needed to be balanced for a person to be healthy. Regular menstruation was the expected purgation of the female body, and so menstruation was believed to be essential for the health of women of childbearing age.

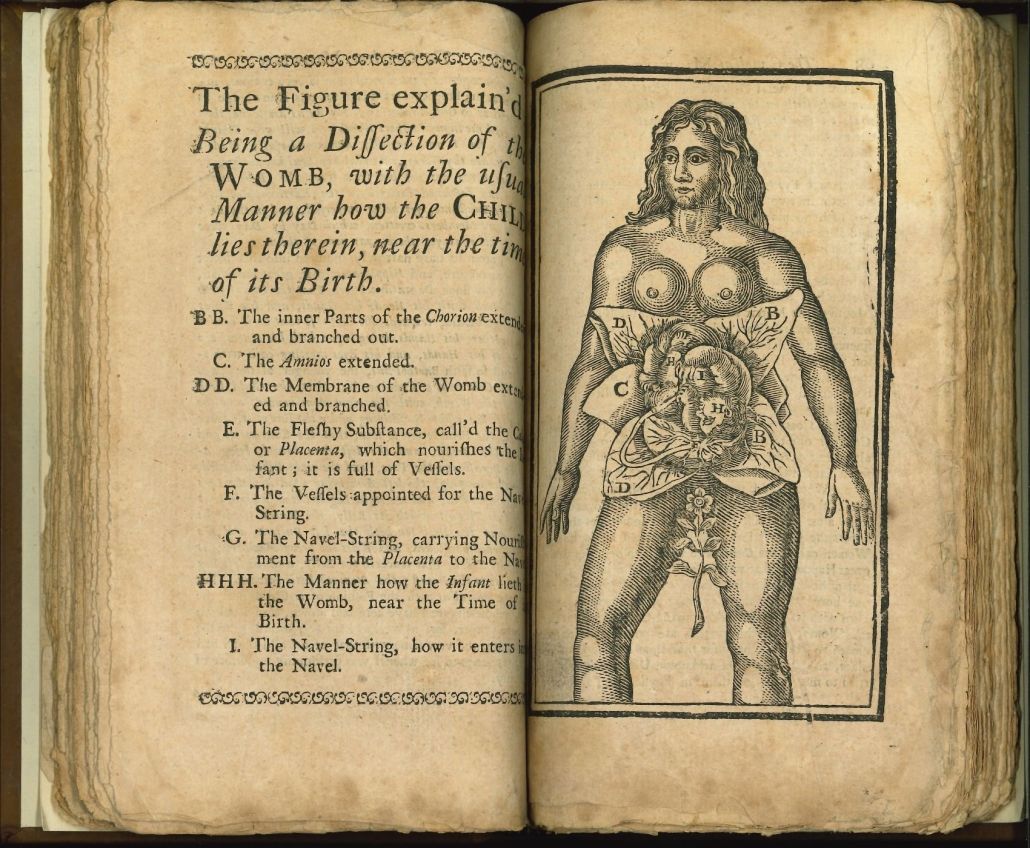

However, one of the main reasons people were so interested in inducing menstruation had to do with conception. Menstruation was thought to ‘clean’ the womb, preparing it for the male seed. The English midwife Jane Sharp even mentioned that having your ‘flowers’ regularly was what made you fertile and ready for the ‘fruit’ – the baby.

You might be thinking that these recipes to purge the womb sound very much like abortion recipes as well. After all, they’re all meant to make the uterus contract and expel its contents, whether that’s a ‘retained period’ or a foetus. And you’re right. The difference between the two was much blurrier than some people would like to believe. This is why abortions (especially before foetal movement) were not usually condemned in premodern times.

What does that tell us? Well, what made a recipe an emmenagogue (a formula meant to stimulate a retained period) or an abortifacient (a recipe meant to provoke an abortion) was not necessarily the ingredients or the methods involved. Rather, it was the intent of the one using the recipe and – crucially – their bodily state.

Let’s come back to the Sweet Apple medicine above. At first, it looks like a recipe to stimulate menstruation. The mention of pain makes us think of dysmenorrhoea, or period pains, as well. Yet opium sounds a bit excessive, doesn’t it? And what about the mention of the woman’s life being in danger? Surely, readers could understand this pain as more than the usual discomfort of menstruation: this was also the pain caused by the purgation itself. If a pregnant person used this formula to provoke an abortion, the opium could help them deal with the pain it caused.

From 1555, when Alessio Piemontese’s Secrets were first published in Italian, to the end of the 17th century, when reeditions and reprints of these recipes started to decline in number, recipes like these multiplied. This allowed recipe books to be marketed as ‘updated’ and ‘improved’ versions of previous editions. But the recipes did not only grow in number. These formulas became more specialised and varied. They included internal medicines (such as pessaries or herbal drinks) as well as external remedies (such as ointments to be applied around the vulva or medicinal baths). The ‘sweet apple’ recipe mentioned above was a less-frequent case of an ‘edible’ remedy. Most of these formats of medicine coexisted in the same book and were offered to readers as different ways of treating the same ailment.

However, these formulas also left ample room for readers to adapt them and personalise them to their lives. People complemented these recipes with their previous knowledge and allowed them to actively manage their bodies. That the same recipe could be used to induce menstruation in the case of amenorrhoea and provoke an abortion is, therefore, not surprising.

The history of medicine is never straightforward, especially where gender is concerned. Menstruation recipes were rarely just one thing; instead, they condensed and combined knowledge in new ways, encouraging different kinds of moral agency and choice from the reader while at the same time alerting/suggesting that many of these emmenagogue recipes could be used as abortifacients.

Recipes like these could (and surely were) used for different purposes, and with varying degrees of success. Books like Piemontese’s Secrets combined ingredients and methods in new ways, but it was the reader who ultimately had control over how a recipe would be used. It was their body that determined if the ‘sweet apple’ would merely stimulate menstruation or provoke an abortion. People had more agency than historians tend to believe. In this instance, it was the body, the womb itself who decided what this recipe would be about. Besides that, it must have tasted lovely. But please don’t go trying 16th-century medicines at home! Just save the apples for baking a pie instead.

References:

Alessio Piemontese, Secreti del Reverendo Donno Alessio Piemontese (Venice: Sigismondo Bordogna, 1555).

Alessio Piemontese, The Secrets of the Reverend Maister Alexis of Piedmont (London: Thomas Wight, 1595).

Jane Sharp, The Midwives Book, Or the whole Art of Midwifry Discovered (London: Simon Miller, 1671).

Further Reading:

Menstruation: A Cultural History, edited by Gillian Howie and Andrew Shail (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005).

Regulating Menstruation: Beliefs, Practices, Interpretations, edited by Etienne van de Walle and Elisha Renne (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2001).

Sara Read, Menstruation and theFemale Body in Early Modern England (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015).