As Christmas approaches, we are bombarded with images of the birth of Jesus Christ – or rather, with depictions of mother and child after the delivery. Indeed, while there are modern reimaginings of what this scene might have looked like, there are few earlier representations of Mary’s labour. How might that scene have looked? How did people conceptualise Jesus’ birth in the past, and how was it different from other births?

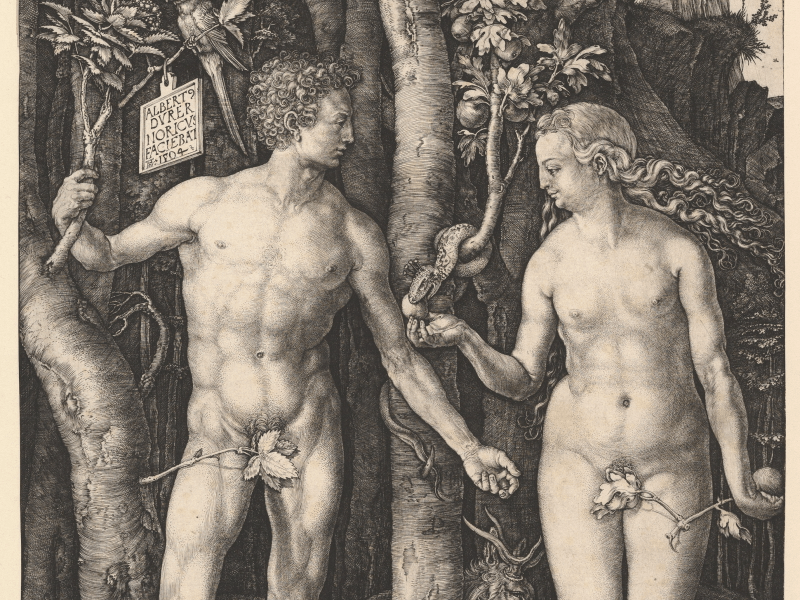

For centuries, women had been taught that painful childbirth was the result of ‘the curse of Eve’. This divine curse defined pain as a God-given bodily experience to the one giving birth:

‘I will greatly multiply your pain in childbirth, In pain you will bring forth children’. (Genesis 3:16)

As daughters of Eve, women shared her punishment for the fall, which was childbirth pain. However, if painful births were the result of the loss of innocence, Mary’s birth could not have involved pain, since hers had been a virgin conception. Indeed, Mary was understood to have been blessed with a pain-free childbirth: no loss of virginity implied no blood, and no pain:

‘Before she was in labour, she gave birth; before her pain came upon her, she delivered a son. Who has heard such a thing? Who has seen such things?’ (Isaiah 66:7)

So, Mary ‘skipped’ the labour phase, as she was exempt from the curse of Eve:

‘for preserving her virginal integrity inviolate she brought forth Jesus the Son of God without experiencing any sense of pain’ (Catechism of the Council of Trent, Part 1: The Creed, Article III).

How was it possible to just ‘skip’ labour, though? St Augustine discussed the physiological process of Jesus’ miraculous birth:

‘In conceiving thou wast all pure, in giving birth thou wast without pain. I answer that, the pains of childbirth are caused by the infant opening the passage from the womb. Now, it has been said above, that Christ came forth from the closed womb of His Mother, and, consequently, without opening the passage. So, there was no pain in that birth, as neither was there any corruption; on the contrary, there was much joy therein for that God-Man was born into the world’ (Summa Theologica Q28,A2, Replies to Objections, and Q35,A6).

So, maybe the reason why there were so few depictions of the Virgin giving birth was that it was difficult for people to conceptualise such a quick, unique birth, in which one goes from being pregnant to holding a baby almost instantly, as if by magic – or a miracle.

In any case, church scholars have spent centuries discussing the puzzling details of Jesus’ birth, and artists have focused on depicting the new family rather than the birth itself. Contemporary artists such as Natalie Lennard, however, render this scene closer to us, highlighting the physicality of giving birth. By representing Mary’s birth as a bodily experience, Lennard arguably renders the miraculous closer, by adding a physical dimension to what some of us see as sacred.

Merry Christmas to all who celebrate it, and happy holidays to those who do not! May we all enjoy a little bit of magic this season, and hope for a better year ahead.

(The Latin translations are mine.)