Content Warning: Discussion of childbirth, obstetric violence, maternal and infant mortality.

On a cold winter evening in 1600, Peter Chamberlen the Younger found himself attending to a labouring woman on the outskirts of London. The mother-to-be had been in labour for over 48 hours, and the situation was dire. Despite his wealth of experience, Peter feared that both the mother and child might be lost. With time running out, he made the fateful decision to use a secret tool that he and his brother, Peter Chamberlen the Elder, had been developing: a pair of obstetrical forceps. Miraculously, the mother gave birth to a healthy baby boy, much to the relief and amazement of everyone present. Little did they know that this life-saving tool, hidden away in a locked box, would revolutionize childbirth and save countless lives in the centuries to come. Just to give you an idea, today in the UK around 7% of deliveries in the NHS involve the use of forceps.

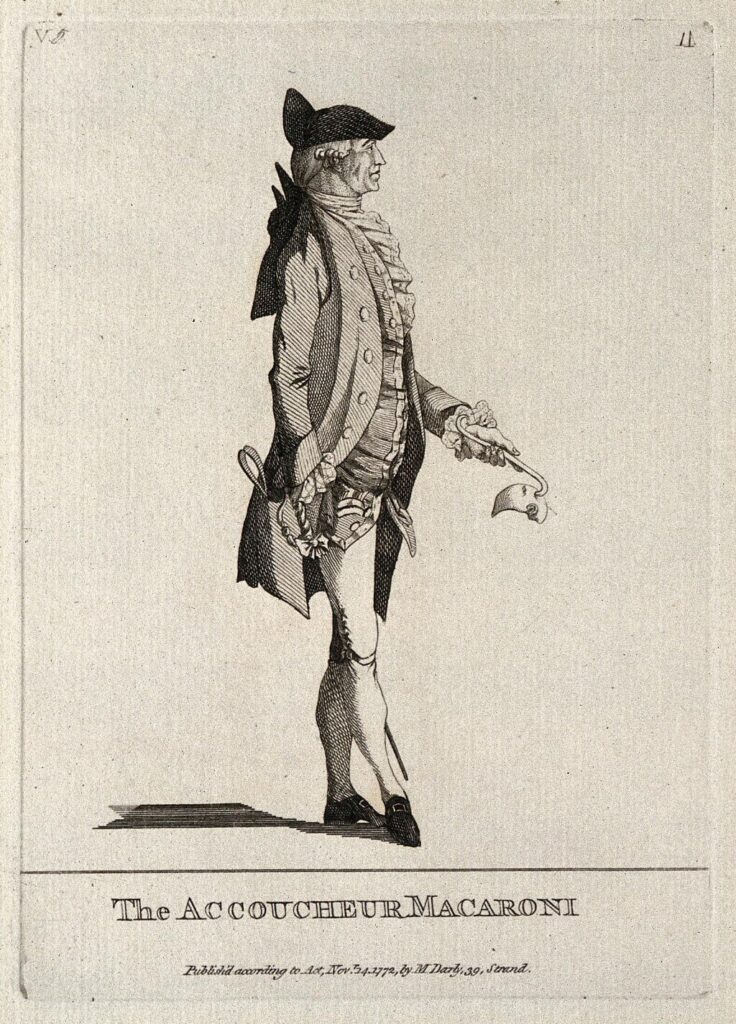

At the same time, the history of forceps highlights the gradual transition of birth from a ‘natural’ to a ‘medical’ event, with physicians competing with midwives and taking over childbirth. The rise of forceps is very closely connected to the creation of the field of obstetrics. To make things even more interesting, for decades this tool was surrounded by secrecy, making us question who should have access to medical knowledge. So, let’s try to get a grip on the history of forceps.

The Origins of Forceps

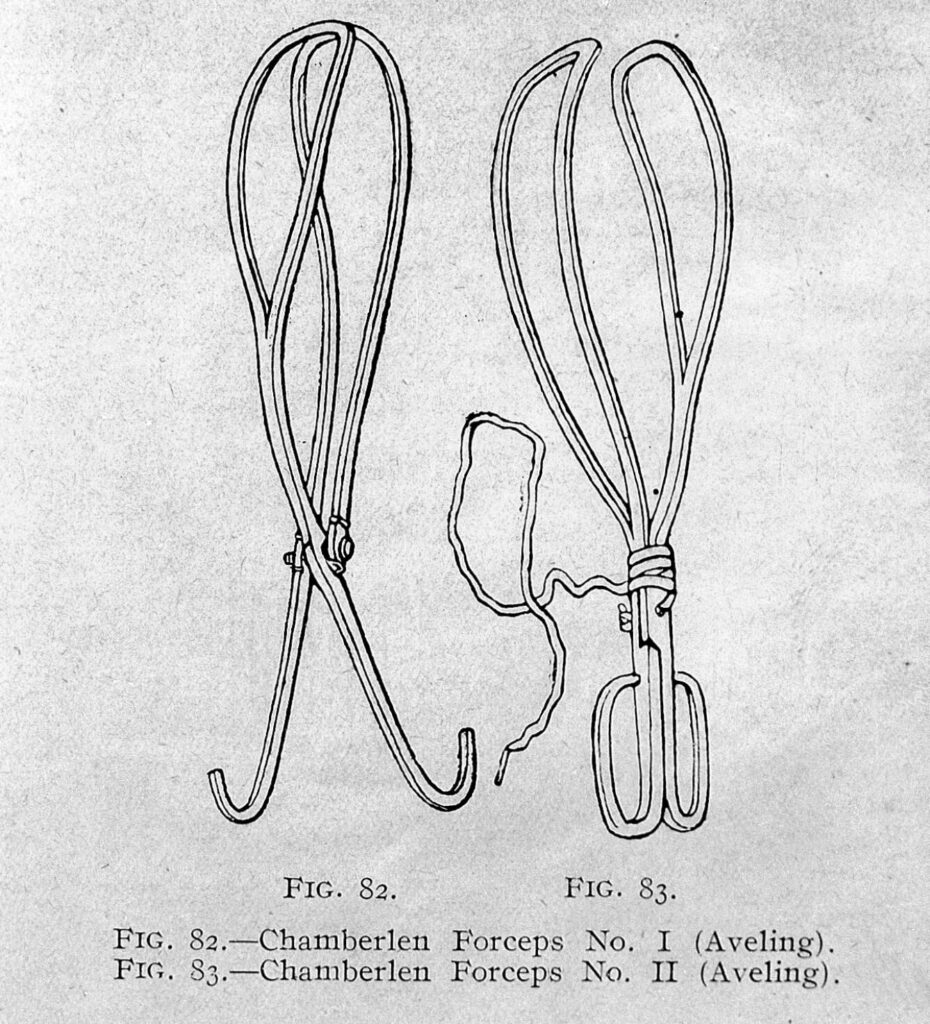

The earliest known references to forceps can be traced back to the ancient Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans, with physicians like Hippocrates and Galen mentioning the use of forceps-like instruments in their writings. The word forceps itself comes from the Latin formus (hot) and capere (to grab). But these early tools were very rudimentary compared to the later, more anatomically refined designs that emerged in the early modern period.

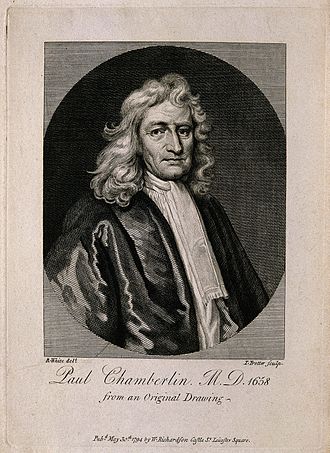

The history of forceps became inextricably linked to the Chamberlen surgeons, especially the brothers mentioned above, Peter Chamberlen the Elder (1560-1631) and Peter Chamberlen the Younger (1572-1626). The Chamberlen family were French Huguenots who emigrated to England in 1569 and became prominent in their field. (Still, no one really knows which of them created the design for their famous forceps.) Peter the Elder served as a physician to Queen Anne, the wife of King James I, and later to Queen Henrietta Maria, the wife of King Charles I. His younger brother was appointed the royal physician to both King James I and King Charles I. But it was their newly designed forceps that cemented their fame.

A Family Secret

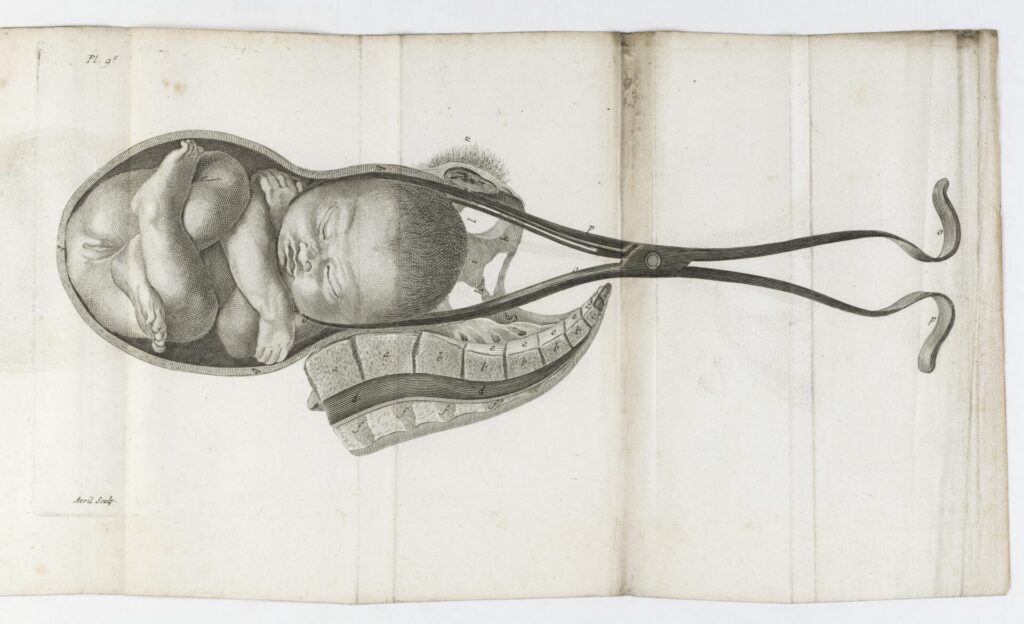

For over a century, the design of this tool was a closely guarded secret since the Chamberlen brothers realised how their forceps set them apart from other medical practitioners, be they midwives, physicians, or surgeons. Before forceps, the situation was difficult for babies who were stuck in the birth canal. Sometimes surgeons were called to remove them with hooks, often in pieces, in the hope of saving the mother.

When the Chamberlens were called to attend difficult births, the brothers brought their forceps in a large (and locked) box. No one was allowed to see the instrument, not even the person giving birth. The labouring mother was usually blindfolded, and all others present were removed from the room. As soon as the baby was born, the secret tool was hidden away in its box once more.

What made the Chamberlen forceps so unique was its unique, ‘gentler’ design: the blades were curved (imagine soup ladles), to conform to the baby’s head, minimising the risk of injury during the extraction. Crucially, the blades could be locked together at the handles with a spring, after being inserted separately, facilitating the delivery. Plus, being made of steel, their forceps were easy to clean.

The Chamberlens’ Detractors

Rumour had it that the Chamberlens had the highest success rates for delivering the baby safely and the mother surviving. Many women believed that they had higher chances of a safe birth with their help, which made the brothers highly sought-after and, unsurprisingly, deeply resented by their competitors. One of their critics even wrote a poem against them ending in:

‘To give you his character truly compleat

He’s Doctor, Projector, Man-Midwife, and Cheat.’

The Chamberlen brothers were members of the Guild of Barbers and Surgeons, who were never highly regarded by physicians since they hadn’t formally read medicine in Oxford or Cambridge. The Chamberlens were also not popular among midwives. In 1634, Peter had petitioned the king to create a Midwives Corporation which, of course, he intended to run. That did not go well with midwives.

Forceps and Secrecy

It probably didn’t help the Chamberlens’ popularity that they refused to share their secrets with other medical practitioners. Keep in mind that this was a time before patents to protect their design and they would make no money from sharing it. Still, when you think about how many people could have been spared if they shared their secrets, it’s hard to sympathise with the Chamberlens. Hugh Chamberlen was unapologetic:

‘My fathers, brothers,and my self […] have, by God’s blessing, and our Industry, attain’d to, and long practis’d a Way to deliver Women in these cases without any Prejudice to them or their infants. […] I will not take apology for not publishing the Secret I mention we have to extract Children without Hooks. […] I do but inform that the fore-mention’d three Persons of our Family, and my Self, can Serve them in these Extremities, with greater Safety than others.’

Meaning that, if you wanted a safe delivery, you better hire a Chamberlen, which meant you had to live in London and be able to afford their fees. Otherwise… well, too bad for you!

Openness at Last

The secret design remained hidden within the Chamberlen family for generations. In 1670, Hugh Chamberlen travelled to Paris to sell the design to the French doctor Francois Mauriceau, one of the most well-known ‘man-midwives’ of the time. You might be wondering how come the Chamberlens were willing to share their design. Well, Mauriceau won a bet. Chamberlen needed to prove that a forceps delivery was quick and safe, otherwise, Mauriceau would have the right to buy the secret.

Mauriceau chose the woman on whose body they would decide their wager: she had rickets and a malformed pelvis. Both mother and baby died following a horrific delivery in which Chamberlen perforated the woman’s womb and Mauriceau attempted a caesarean section. We know next to nothing about her, the woman who died over a bet between two medical practitioners. In the end, the sale wasn’t made, and Chamberlen returned to England.

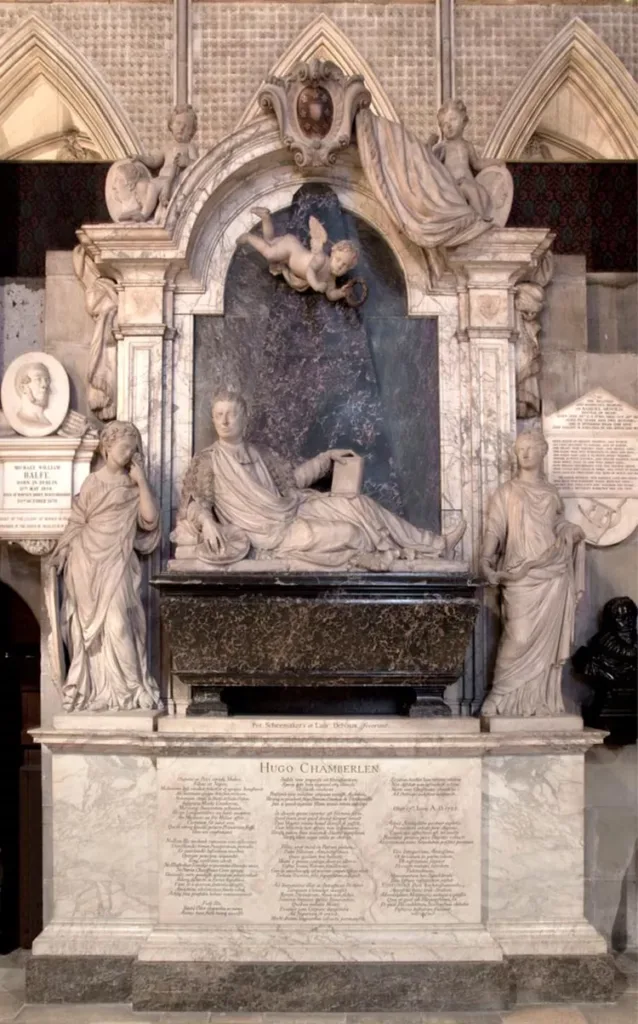

According to legend, he eventually moved to the Netherlands, where he sold the design to a local doctor. However, the story goes, this ‘forceps’ was only composed of one half, and was, of course, useless. Hugh Chamberlen’s son, also named Hugh, eventually allowed the design to be made public in England in the early eighteenth century. There is even a monument to him inside Westminster Abbey.

But where did the original forceps go? Well, it was hidden (probably by Peter Chamberlen) under the floorboards of his Essex home, where it was found in 1813, by the mother of the family then living there. By then, many competing designs had been created by other obstetricians.

After the Chamberlens

Forceps opened the door to a flood of innovations and ‘birth gadgets’, including the (to me, very silly) ‘self-operated forceps’. Can you imagine trying to use forceps on yourself while giving birth?!

Post-forceps, medical men were increasingly present in the birth room. The Chamberlens became known as ‘man-midwives’, helping popularise this concept. Other changes followed; midwives were used to attending people giving birth on birth stools or chairs, but physicians preferred their patients lying down so that they could use their tools more easily.

Forceps became popular for many reasons, including that physicians believed that some elite women were ‘too fragile’ to push. However, their use was contentious from the beginning. Just take a look at this passage from a poem against forceps, penned by John Maubray, the author of the Female Physician:

[Forceps] Kill many more INFANTS than they save and ruin

Many more WOMEN than they deliver

[…] I would advise you to practice Butchery rather than MIDWIFERY…

Following the height of their popularity in the nineteenth and early twenty centuries, their use gradually faded, especially as caesarean sections became more widespread. Still, the history behind forceps begs one of the most crucial questions in the social history of knowledge: who should have access to knowledge? Crucially, it also asks the (always feminist) question: who should make decisions about our bodies?

References:

John Maubray, The Female Physician (London: James Holland,1724).

Francois Mauriceau, The Diseases of Women with Child, translated and annotated by Hugh Chamberlen (London: T. Cox and J. Clarke, 1793).

Further Reading:

A. C. Banks, Birth Chairs, Midwives, and Medicine (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1999).

K. Das, Obstetric Forceps: Its History and Evolution (Leeds: Medical Museum, 1993).

B. Hibbard, The Obstetrician’s Armamentarium (San Anselmo, CA: Norman, 2000).

R. H. Epstein, Get me Out: A History of Childbirth from the Garden of Eden to the Sperm Bank (New York: Norton, 2010).