What to do, what to buy, what to organise, what to cook, what to read… I made so many lists when I was pregnant that it would take a new list to organise them all! Expectant parents are bombarded today with information about how to prepare for the arrival of a baby. Yet childbirth itself has never been more medicalised and arguably out of families’ control. But what about the past, before social media, Amazon wish lists, and insipid hospital food? Here’s a list of how to prepare for a new baby in 17th-century England.

Caveats: I have considered an ‘average’ English family, composed of a married woman and man of middling social status (think of the husband as a yeoman or merchant). The things listed here would usually follow this order, but each community and family had specific practices. Like all lists, this is non-comprehensive but should give you an idea of what life was like for new parents at this period.

1. Confirming the Pregnancy and Spreading the News

Unlike today, a missed period was not usually thought to automatically indicate pregnancy. It wasn’t until quickening that pregnancy was confirmed (when foetal movement could be first felt). From then on, people could announce the news. Some mothers might prepare in case childbirth didn’t go smoothly, although that wasn’t very common. (You can read more about writing to the unborn child here.)

2. Engaging a Midwife

Most people lived close enough to a midwife to have her help in the delivery. For the ones living in cities, there was a choice of practitioners. Friends’ recommendations, price, and reputation were all considered when a midwife was hired.

3. Hiring a Nurse

A temporary nurse would be hired to help around the house for the month following the delivery. She would help take care of the baby and mother, but her main role was to perform the domestic duties left unfulfilled by the one who had just given birth.

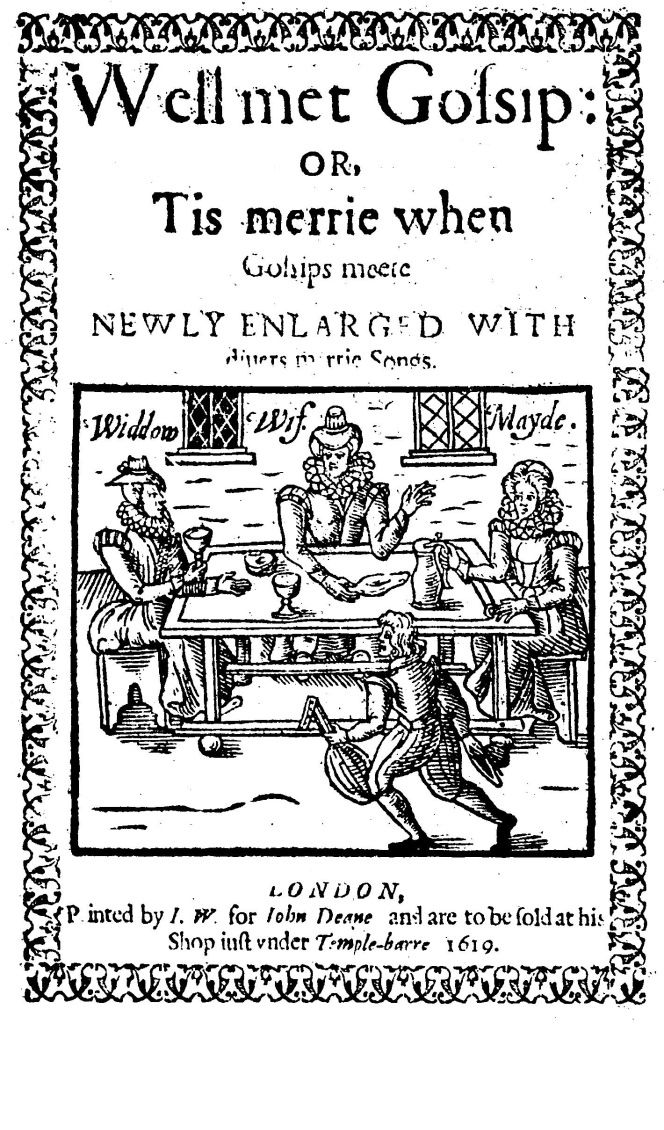

4. Inviting the Gossips

In the final months of the pregnancy, the expectant mother would issue invitations to her female relatives, neighbours, and friends, to attend her birth as her ‘gossips’, or ‘god-sibs’ (siblings in God). The women she chose would help her and the midwife, by making food, keeping company, and supporting her during the birth. The mother could expect at least half a dozen gossips.

5. Preparing the Birth Chamber

As the birth approached, the family would make sure to have the essential items for the delivery: candles, extra linen, a straw pallet bed, maybe a birth stool or chair, swaddling bands for the newborn baby, food and drink for everyone involved in the birth, herbal medicines, and (hopefully) the midwife’s fee. Before the Reformation, relics could be used, as well as rosaries, crucifixes, prayer books, and birth girdles with images of the Virgin Mary or St Margaret. (You can read about an amazing 15th-century birth girdle here.) The expectant mother would also seek the blessing of her local priest for a safe delivery.

6. Summoning the Midwife and Gossips

When labour began, the husband, perhaps helped by a servant, would go from door to door calling the gossips and midwife to come to attend his wife during the delivery. (This was later called ‘nidgeting’.)

7. Enclosing the Mother

If she wasn’t already in confinement, the gossips and midwife would move the labouring woman to a separate space from men as soon as they arrived. This was usually already set up, at least in part. Windows would be shut and covered by curtains or makeshift fabrics, to keep the daylight and the air out. Keyholes would be blocked so that no air came through them either. Candles would be lit as well as a fire. A birthing stool would be available (often brought by the midwife) for the use of the labouring woman.

8. Nourishing the Mother

The gossips would make sure that the person giving birth received nourishment (often under the midwife’s advice). They would offer her warm drinks made of wine, especially caudle, which contained sugar, spices, and eggs. (Check out this 14th-century recipe for caudle!)

9. Delivering the Baby

Midwives’ techniques varied greatly, but they were usually highly experienced. They might examine the woman to see how the birth was progressing and suggest which position would work best for the delivery. They could also manually remove the placenta after the birth if so needed. If the baby was unresponsive, the midwife would probably be the one to revive it. The midwife or a gossip would tie and cut the umbilical cord.

10. Cleaning and Swaddling the Baby

One of the gossips would probably be responsible for washing and swaddling the infant. Swaddling was deemed essential for babies in this period, to make sure their limbs grew correctly. It was also thought to keep babies calm and to make life easier for the one taking care of them, as it helped babies sleep.

11. Showing the Baby to the Mother and Breastfeeding

After the baby was ready, the mother would finally be able to see it. Breastfeeding would be encouraged unless the family was wealthy enough to hire a wet nurse. In that case, she would probably have been engaged earlier, around the same time as the nurse. Breast milk could be used to treat abscesses in the mother following childbirth, as well as eye or skin conditions in the newborn baby. (I wrote about breastmilk as medicine here.)

12. Lying-In

After the delivery, the mother’s lying-in period would begin. This would last for around 3 to 5 weeks and be comprised of three phases.

- In the first stage, she would be in her bed, and the room would remain darkened. The mother’s vulva would be washed with herbal solutions, but her sheets usually wouldn’t be changed. She would not perform any household duties. A nurse, hired for the lying-in period, would help around the house.

- In the second stage of lying in, she would be able to sit up and move around the room, and her bedclothes would be replaced. This was when close female friends would usually visit her. It was a time of female sociability and bonding. Caudle would be offered to visitors as well.

- In the final stage of her lying-in, the mother would be able to move around the house, but not leave it. More visitors would drop by, including men. Light household duties could now likely be performed by the mother.

Significantly, it was usually the person who had given birth who decided when to move from one stage of lying-in to the next.

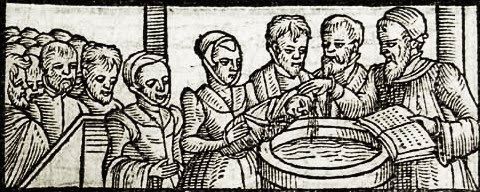

13. Baptism

During the lying-in period, the baby would usually be baptised, without the parents’ presence. The godparents (usually three people) would act in their place, and the baby would be welcomed to the community.

14. Tipping the Midwife

At or right after the baptism, the godparents and gossips would usually tip the midwife for the safe delivery of the child. The father of the child would typically have paid and tipped the midwife after the birth.

15. Resuming Sexual Activity

It was inadvisable for sex to take place until the lying-in period was completed. Once the month was over, however, husband and wife could go back to sleeping together. (Of course, it’s impossible to know how much this injunction was followed.)

16. Churching

After her lying-in period was complete, the mother should only go outside the house after having been ‘churched’. (She usually wore a veil on the way to church to go around this unpractical norm.) Escorted by her gossips, the mother would go to church and kneel in a specific area separate from others, often called a ‘childbed pew’. During the service, the woman would thank God for her safe delivery. Specific Psalms would be said (116, 121, or 127), as well as the Lord’s Prayer (Kyrie Eleison). She would then make offerings to the priest and clerks and would be welcomed back to the community. This ceremony was much contested during the Reformation – but that’s a topic for another day!

Giving birth in 17th-century England was a process of separation, transformation, and reincorporation full of specific customs. Gender was a crucial aspect of these practices: the woman giving birth was separated from men and surrounded only by those of her sex and finally, reintegrated into society. Significantly, this was a female collective ritual, that inverted the usual power dynamics within families. In a patriarchal society such as 17th-century England, that was no small feat. This female world assured that, after birth, the mother’s body belonged to her, not her husband, at least for a while. She wouldn’t fulfil her domestic or sexual duties. This is why I find the female culture of childbirth so fascinating: it is a form of resistance, a fight for autonomy – even if short-lived.

Further Reading:

David Cressy, Birth, Marriage, and Death: Ritual, Religion, and the Life-Cycle in Tudor and Stuart England (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997).

Amy Licence, In Bed with the Tudors: The Sex lives of a dynasty from Elizabeth of York to Elizabeth I (Gloucestershire: Amberley Publishing, 2012).