When most of us think of aphrodisiacs nowadays, we imagine a menu of oysters and chocolate, perfect for Valentine’s Day – even if the odd garlic or fenugreek makes an apparition here and there. In the modern world, aphrodisiacs are meant to stimulate the body and increase sexual pleasure: the word comes from the Greek goddess of love and sex, Aphrodite. Early modern people, on the other hand, understood them as capable of enhancing the body’s fertility too. Sexual pleasure was thought to increase the chances of conception: lust was an integral part of reproduction. But why was there a connection between procreation and aphrodisiacs? And what kinds of aphrodisiacs did people use?

Browse through pretty much any medical book written between the sixteenth and the eighteenth centuries and you will find plenty of things described as capable of provoking lust or ‘venery’ (from the Roman version of the goddess, Venus – it’s the same origin as ‘venereal disease’). These could go from ordinary, everyday foods (such as carrots and milk) to exotic and expensive products from the New World (such as chocolate and vanilla). Although aphrodisiacs could be used in various ways, historical sources mainly discuss them within the framework of matrimony and procreation: they were used by married couples to help them conceive. For conception to occur, the quality of the male seed (sperm) was important; in women’s case, it was a healthy monthly menstruation that was needed. Still, it was usually thought that heat and pleasure were essential for both, which explains why most aphrodisiacs were recommended for everyone who wanted to conceive.

Aphrodisiacs were everywhere: the overlap between aphrodisiacs and remedies for infertility and cures for barrenness and impotence is such that these categories become almost meaningless. This was especially important at a time of high infant mortality and when procreating was the main goal of marriage: it was only natural for couples to seek to maximise their fertility. Moreover, in a patriarchal society, women’s main social role was connected to motherhood and male virility was demonstrated by the production of offspring. This meant that having children was expected of most people and that infertility was a serious problem. Don’t get me wrong: people did also try to regulate their fertility through contraceptives and abortions. Still, the ubiquity of aphrodisiacs in early modern books, pamphlets, ballads, and plays testifies to the extent to which they were a part of everyday life. Knowing aphrodisiacs was just a part of most people’s everyday medical and sexual knowledge.

So, what did early modern people consider aphrodisiacs? Well, the short answer is… lots of things. This is because the list included traditional and new remedies, which derived from several different medical systems, from the Hippocratic and Galenic humoral medicine to astrological, folkloric or Aristotelian beliefs. Bodily heat was usually considered vital to sexual activity and fertility: heat could also facilitate the conception of a male child, as men were believed to be hotter than women in general. So, it was particularly important for those who needed a male heir. Therefore, in Galenic medicine, which tended to treat the body through opposites, an infertile body should be treated with warming foods and spices (game meat, birds such as hens, sparrows and pheasants, rocket, peppers, cinnamon, and nutmeg, among others). The opposite was also true: to diminish libido, anaphrodisiacs that cooled the body could be used, such as water lilies.

Aphrodisiacs were believed to be so powerful that they could even be used to treat infertility caused by witchcraft. Still, many of the foodstuffs recommended strike our modern sensibility as unexpected: ‘windy meats’ or flatulent foods, such as beans and peas, were also recommended to help a couple conceive. For men, it was believed that wind could help attain and maintain an erection, though women were warned about the dangers of excessive windiness in the womb.

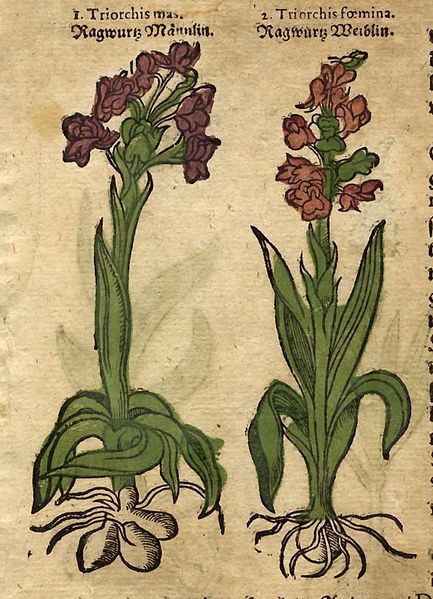

The body could also be stimulated through sympathetic medicine and the doctrine of signatures, according to which the external appearance of plants held clues to occult virtues it had to treat the body. This meant that phallic plants such as carrots and parsnips could be understood as capable of facilitating sexual activity. Satyrion (or ‘dog stones’) was widely believed to be an aphrodisiac because of its testicular appearance. The name itself comes from the mythological Greek satyrs, known for their lecherous nature.

In popular culture, these beliefs deriving from the doctrine of signatures also explained why animal genitalia were often considered aphrodisiacs. The sexual power of animals usually considered highly lascivious, such as goats and birds, was believed to be transmitted through the consumption of their bodies. Animal testicles and penises (from foxes, bulls, and goats) as well as wombs (from dogs or hares) were especially valuable if the animal was killed during copulation, as the organs would then have their reproductive virtues enhanced. (Yes, seriously. I wish I was making this up!)

All these ingredients could be consumed by themselves (as ‘simples’) or in combination with others (‘compound medicines’), which could enhance their effect. They served to heat the body and encourage intercourse, to prepare the womb for conception and improve the quality of the male seed (sperm). In the case of seed, salt and ‘salty foods’ had been traditionally recommended, such as seafood. As the Neapolitan humanist Giambattista Della Porta wrote, in a recipe called ‘That a woman may conceive’:

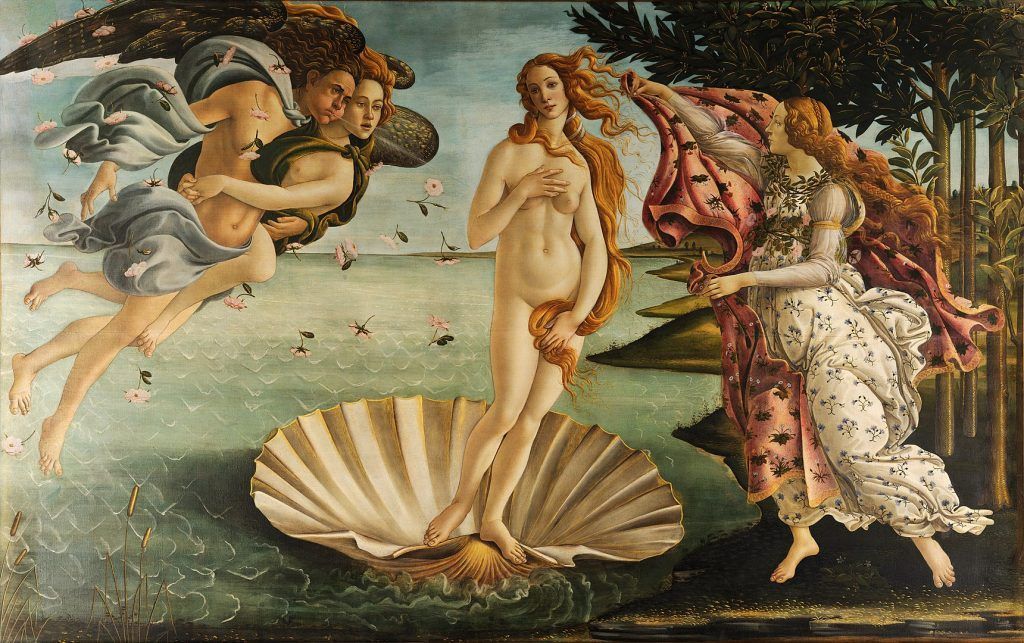

Salt also helpeth Generation: for it doth not only heighten the Pleasures of Venus, but also causeth Fruitfulness. […] Hence the Poets feigned Venus to be born of Salt or the Sea.

According to Greek mythology, Aphrodite had been born from the sea, which explained seafood’s properties as aphrodisiacs – think of oysters and caviar, for instance. Because male seed was partly composed of salt, these substances served to strengthen it, improving its quality and fertile potential.

I know what you’re thinking: none of this is very sexy. I agree. But that’s the thing; for us, aphrodisiacs are connected to pleasure only, whereas for early moderns, it was impossible to separate this pleasure from the fact that it also enhanced the chances of conceiving a child.

So, here’s a short (and non-exhaustive) summary of what early modern people considered aphrodisiacs, in no particular order: rocket, mustard, pepper, cinnamon, cress, ginger, galingale, myrrh, chicken, partridge, capons, pheasants, game meat, doves, birds like sparrows, aniseed, caraway seeds, saffron, cloves, balsamic, sea holy (eryngo), satyrion, nutmeg, cantharides, parsnips, turnips, carrots, eggs, hares, green geese, crawfish, crab, lobster, oysters, cuttle-fish, polypus, quails, foxes, milk, chestnuts, almonds, pine nuts, pistachios, artichokes, radishes, beans, peas, rice, barley, veal, onions, leeks, mushrooms, asparagus, garlic, leeks, sugar, caviar, eels, hazelnuts, aubergines, lemons, trout, milk, chickpeas, chocolate, vanilla, figs, musk, and amber. My favourite is probably cantharides, the ‘Spanish fly’, described by English midwife Jane Sharp in 1671 as having Viagra-like effects, making the penis ‘continually standing’.

In any case, good luck cooking up something for Valentine’s Day that wouldn’t be considered an aphrodisiac by early modern standards… Just make sure you steer clear of eating animal genitalia. Chocolate is much nicer!

References:

Theophile Bonet, Mercurius compitalitius: or, A guide to the practical physician (London, 1684).

Giambattista Della Porta, Natural Magick (London, 1658).

A Marsh, The ten pleasures of marriage relating all the delights and contentments that are mask’d under the bonds of matrimony (London 1682).

John Sadler, The sick womans private looking glasse (London, 1636)

Further Reading:

Jennifer Evans, Aphrodisiacs, Fertility and Medicine in Early Modern England (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2014).

Angus McLaren, Reproductive Rituals: The Perception of Fertility in England from the Sixteenth Century to the Nineteenth Century (London, 1984)

Philippa Pullar, Consuming Passions: A History of English Food and Appetites (London, 1970).