I was reading Christmas: A History, by Judith Flanders, and I came across a passage I just had to share with you. Victorian Christmas could be an incredibly elaborate affair for the upper classes, but what was it like for those who were not so lucky? How about the house servants? Well, let me read you a short passage from the 1863 diary of a “maid-of-all work” in London, Hannah Cullwick.

On the 23rd of December, Hannah wrote:

“I got up early & lighted the kitchen fire to get it up soon for the roasting – a turkey and eight fowls for tomorrow, being Christmas Eve, & forty people’s expected & they’re going to have a sort o’ play. […] [I’m] Very busy indeed all day & worried too with the breakfast & the bells ringing so & such a deal to think about as well as work to do. I clean’d 2 pairs o’ boots & the knives. Wash’d the breakfast things up. Clean’d the passage & shook the door mat. Got the dinner & clean’d away after, keeping the fire well up & minding the things what was roasting & basting ’em till I was nearly sick wi’ the heat & smell… […] We laid the kitchen cloth & had our supper & clean’d away after. I took the ham & pudding up at 12 o’clock, made the fire up & put another on & then to bed. Came down again at 4… The fire wanted stirring & more coals on & when I’d got the pudding boiling again I went to bed till after 6. Got up & dressed myself then & clean’d the tables & hearth & got the kettle boiling & so began.”

It’s just never-ending work, in a hot kitchen. And it’s not even Christmas eve yet! Note that she says she’s “worried.” It’s not just physical labour; it’s the mental load. She cleans boots, knives, mats, gets dinner, cleans it away… and then the physical toll hits. After not much sleep, Hannah is ready to start working again.

So, on the 24th of December, she writes

“After breakfast I clean’d a pair o’ boots & lighted the fires upstairs. Swept and dusted the room & the hall. Laid the cloth for breakfast & took it up when the bell rang. Put the beef down to roast. Clean’d the knives. Made the custards & mince pies – got the dinner up. Clean’d away after and wash’d up in the scullery. Clean’d the kitchen tables and hearth. Made the fire up again & fill’d the kettle… We had supper in the kitchen & then I dish’d up for the parlour. […] Mr Saunderson came & spoke to us servants & was going to shake hands but I said ‘My hands are dirty, sir.’ […] After supper was over the Master had the hot mince pie up wi’ a ring & sixpence in it – they had good fun over it. […] We had no fun downstairs, all was very busy till 4 o’clock & then to bed.”

So, they had good fun over it, upstairs. We had no fun downstairs. That is the Victorian Christmas in a nutshell.

So, not exactly a fun Christmas Eve. How about Christmas itself? Let’s see what Hannah did on the 25th of December:

“Got up at eight & lit the fires. Took the carpet up & shook it & laid it down again in the dining room. Rubb’d the furniture & put straight. Had my breakfast. Clean’d a pair o’ boots. Wash’d the breakfast things up & the dishes. Clean’d the front steps. Took the breakfast upstairs. Got the dinner & fill’d the scuttles. The family went up the Hill for the evening & I clean’d myself to go and see [my sister] Ellen, but I’d such a headache & felt so tired & sleepy I sat in a chair & slept till 5 & then had tea & felt better… Had a little supper & home again & to bed at 10.”

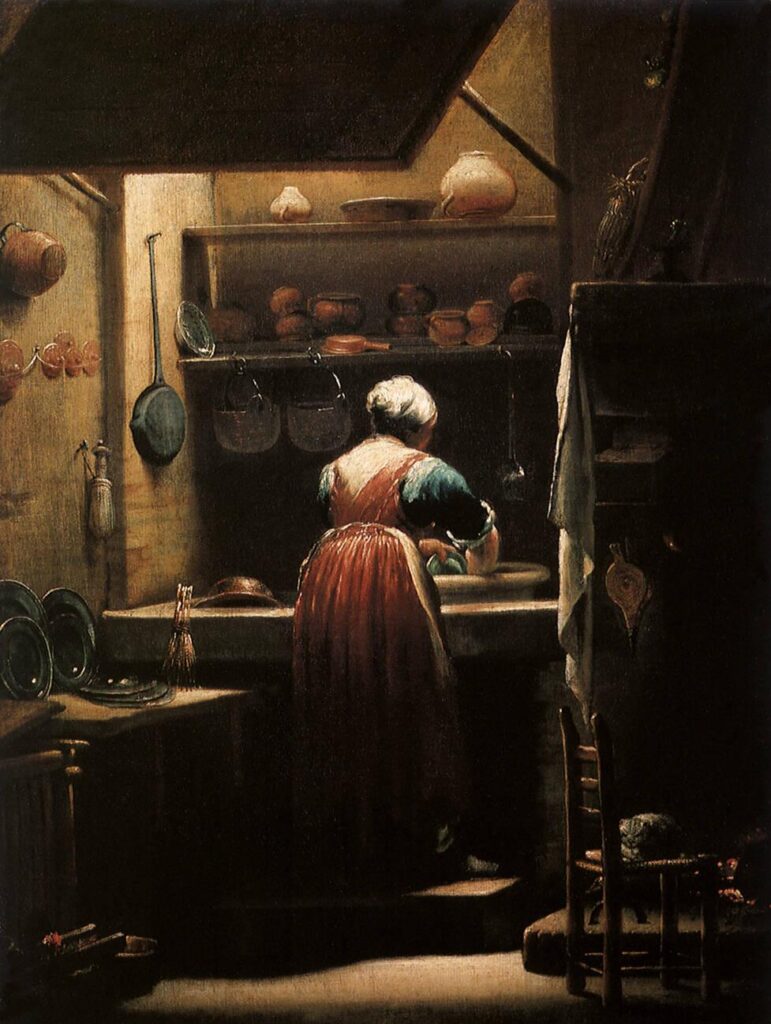

Hannah Cullwick’s diary for these days is essentially a list of everything she did – and of course, it’s fair to assume she did loads of other tasks, too. For a woman like Hannah, working as a “maid-of-all-work” in mid-Victorian London meant devoting nearly every waking hour to domestic labour. The notion of a “maid-of-all-work” was common when a family could afford few or only a single servant instead of hiring separate staff for cooking, cleaning, laundry, boots, fires, and more. In such households, that one servant had to combine the tasks of kitchen maid, housemaid, and scullery maid. For Hannah, the long, grinding process of lighting fires, cleaning boots, cooking, washing up, polishing, etc. would have been a typical workload for a general servant in a modest but service-reliant household. Isabella Beeton’s famous household manual called this “the most fatiguing and trying position of all.” And Hannah’s diary proves it. While the family upstairs enjoyed the “magic” of Christmas, Hannah was the engine room that kept it running – invisible, exhausted, and smelling of roast turkey and coal dust.

Hannah’s lived reality also reflects the larger scale of domestic service in Victorian England. Domestic service was the largest single employer of women in Britain during the nineteenth century. Servants slept and worked “below stairs”, often in cramped, modest quarters tucked away in attics, basements or service wings away from the family’s living and entertaining spaces. (And I think that’s something that a series like Downton Abbey depicts well, though it’s set in a later period, and it’s, of course, a very idealised representation of this lifestyle). Working hours were long, often from before dawn until well after dark, with very little time for rest, recreation or privacy. In fact, the day after Christmas was traditionally the servants’ real holiday. That’s why we call the 26th ‘Boxing Day’ – it was when most servants received their ‘Christmas boxes’ from employers and were finally allowed to go home to their own families.

This diary shows that domestic service, while pervasive, was not comfortable or genteel. For many young women of the working class, service offered relative security compared to factory or field labour – but at the price of long hours, hard manual work, little privacy and a life always “on call”. Hannah’s own words and the broader historical record reveal a world in which Christmas for domestic servants was not a holiday at all, but simply one more day in an endless cycle of work. So, next time you feel stressed about cooking one Christmas dinner, spare a thought for Hannah Cullwick. She made the season bright for everyone else, even if she slept through her own holiday.

References:

Samuel and Sarah Adams, The Complete Servant (1825).

Isabella Beeton, The Book of Household Management (1861).

Hannah Cullwick, The Diaries of Hannah Cullwick, Victorian Maidservant. (Various editions; diary entries quoted from the 23–25 December 1863 entries.)

Judith Flanders, Christmas: A Biography (2017).

Henry Mayhew, London Labour and the London Poor, vol. 3 (1861).

The Diary of a Victorian Housemaid (1981; original 19th-century manuscript).

“Victorian Maid-of-all-Work: A Miserable Life.” Owlcation, accessed 2025.

“Victorian Daily Life.” English Heritage, accessed 2025.

“What Were Georgian and Victorian Servants’ Rooms Like?” National Trust, accessed 2025.

“Victorian Servants.” Victorian Children, accessed 2025.