“…considering the total antipathy I had toward matrimony, the convent was the least disproportionate and most honourable decision I could make…”

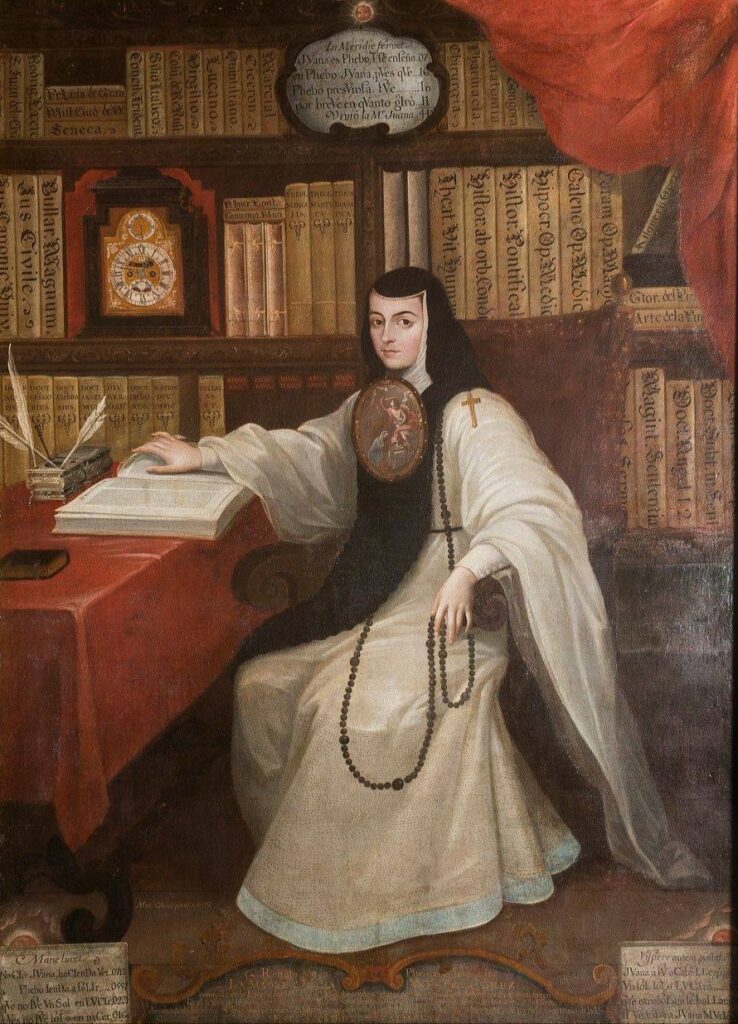

Who would choose a convent over marriage? Well, meet Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, who called herself the “worst nun in history”, built a private library in a convent in colonial Mexico, and argued with bishops, claiming that women had every right to study and learn, just as she did. Let’s talk about this controversial nun, who unapologetically chose the convent over marriage… Because of books.

Part 1 – “The Worst Nun in History”

Juana Inés was born in the mid-17th century in the province of New Spain, which is Mexico today. She was a precocious child who devoured books from the time she was just 3 years old. She learned Latin, theology, science, and classical literature largely by teaching herself, which wasn’t usual for a woman of her time. As an adolescent, she impressed the local aristocracy with her command of philosophy and rhetoric and served for a time in the viceroy’s household before choosing the convent life. As I mentioned earlier, this was not primarily from mysticism or faith, but because the convent offered more room for reading and writing than marriage would have allowed. (No wonder she called herself the “worst nun in history”…!) So, the convent would require some adjustment.

As Juana writes, what she wanted was to

“live by herself, have no obligatory occupation that would limit the freedom of her studies, or the noise of a community that would interfere with the tranquil silence of my books”.

This life choice is often presented by feminists as an early “workaround” for a woman who wanted serious intellectual work, and you can see why.

Still, although she had her books, religious life wasn’t always easy, as she had to conform to what was expected not just of a woman, but a nun. Sor Juana struggled. She was a scholar, a poet, and a playwright, and she became increasingly famous. In a letter to her confessor entitled “Spiritual Self-Defence”, she talks of feeling persecuted and envied by those around her. She writes:

“Women do not like it when men surpass them, or when it looks as though I am the men’s equal; some wish I did not know as much, some say I should know more if I am to be so celebrated. Old women do not wish others to know more than them, young women do not wish others to look good, and all wish that I should live according to their expectations. And from all sides a kind of martyrdom is created, which I am not sure other people have faced.” Oh, the impossible standards women face!

The main issue for those around her was that Sor Juana was attracting the social elites, who would flock to the convent to meet her. And so, she asks:

“Is it my fault that their excellencies like me? Should I deny meeting important people? Should I resent that they honour me with their visits?”

Sor Juana was right – more and more people were paying attention. But things were about to escalate, and a big polemic would start. Sor Juana openly criticised a famous preacher, and was scolded by the bishop who hoped women like Juana would just stay quiet… and, ironically, he was writing under a female pseudonym.

Part 2 – Polemics, Satire, and “Feminism”

For background, the polemic started when, in 1690, Sor Juana published a text called Carta Atenagórica, or “Letter Worthy of Athena”, which already gives you an idea of how highly she thought of herself – and rightly so, but it didn’t make her very popular among the male clergy. This was a densely argued theological critique of a sermon by the renowned Jesuit preacher Antônio Vieira, who was celebrated throughout the Portuguese and Spanish empires. I mean, I remember studying him at school in Brazil.

Sor Juana approached his sermon with a calm but formidable rigour, drawing on Scripture, the Church Fathers, and scholastic logic. She showed the logic fallacies and inconsistencies in the male preacher’s thinking. Why is this important, you may be wondering? Well, it’s not really about the theological arguments; it’s about the fact that this was a public critique written by a woman in a period when women were expected to remain silent in such debates. Sor Juana insists that arguments must be evaluated on their merits, not on the authority of the speaker. It’s hard to overstate how bold this was, saying that intellect (whether the person was a man or a woman) should count more than hierarchy or gender.

Following this episode, the Bishop of Puebla – who had supported her publication of this critique – decided to “put her back in her place”, as it were. So, he reprimanded her, under the pseudonym “Sor Filotea,” essentially arguing that theological reasoning was improper for a woman. This argument was often made using a passage of the Bible that says:

“Let your women keep silent in the churches, for they are not permitted to speak; but they are to be submissive, as the law also says”.

What happened then? Well, Sor Juana wrote a reply to this Sor Filotea, arguing why women should be educated and speak their minds. This was the most dramatic intellectual confrontation of Sor Juana’s career, and this text would become her great defence of women’s right to study, read, and write. It’s hard to read her long and passionate defence of women’s intellectual autonomy and not see her as a kind of “proto-feminist”. It’s particularly funny to me that she would sign this letter as “Yo, la peor de todas las mujeres (the worst of women), Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz. As the other letter indicates (the one “worthy of Athena”), Sor Juana didn’t struggle with self-esteem. This is a conventional, rhetorical humility that she is performing here, typical of religious writing. Using this at the end of a defence of women’s right to an intellectual life is definitely ironic.

But there’s more. Sor Juana wrote lyrical and satirical poetry. My favourite poem is called “Silly Men Who Accuse”, which is an accusation of double standards – and it’s a delight to read. This is how it starts:

“Silly, you men-so very adept

at wrongly faulting womankind,

not seeing you’re alone to blame

for faults you plant in a woman’s mind.”

Another part goes:

“You batter her resistance down

and then, all righteousness, proclaim

that feminine frivolity, not your persistence, is to blame.

When it comes to bravely posturing,

your witlessness must take the prize:

you’re the child that makes a bogeyman,

and then recoils in fear and cries.”

So, Sor Juana is saying that men create the “faults” they condemn in women, and that they’re hypocrites; it’s a biting, ironic, and funny poem.

Part 3 – A Multicultural Writer?

If I haven’t persuaded to go read Sor Juana’s works yet, perhaps this will. A tantalising part of Sor Juana’s reputation is her supposed competence in Nahuatl (the language of the Aztec/Nahua elites), and her incorporation of Nahuatl lines in a few works. Now, we saw how incredibly learned she was and how she loved languages, so it wouldn’t be surprising that she would study Nahuatl, living in colonial Mexico.

Some scholars claim that she composed bilingual Spanish–Nahuatl pieces used in religious popular song; if she did, it would be a sign of her linguistic abilities and the multicultural environment of New Spain. Recent scholarship, however, reminds us to be cautious: while some pieces associated with her include Nahuatl refrains, attributing full Nahuatl authorship to Sor Juana is contested. What we do know is that Sor Juana certainly set Spanish and occasionally Nahuatl phrases into performance contexts, but whether she wrote original Nahuatl poetry as a fluent Nahuatl author remains debated.

In any case though, regardless of how well or how much she wrote in Nahuatl, or how fluently she spoke, I think this is telling about her. She was clearly who loved to learn and study all that she could; she was open-minded and curious. And, if you’re living in colonial Mexico in the 17th century, why wouldn’t you learn Nahuatl if you could?

Final Thoughts

Sor Juana was one of the most striking intellectual figures of the seventeenth century, who used her voice to argue – sometimes subtly, sometimes explicitly – for a woman’s right to learning. She’s sometimes called a “proto-feminist”, or the “first feminist of the Americas”. As it’s often the case, labels like these are powerful but lack nuance and can quickly fall into anachronism. Many of her arguments resonate with feminist thinking, especially where intellectual agency is concerned. Her poems mocking men are irresistible and deliciously funny, ridiculing patriarchy and gender norms. She anticipated feminist concerns, but she did so within the constraints of her political and religious moment.

As the polemic with the Jesuit preacher and the bishop shows, Sor Juana saw the value in knowledge for its own sake; intellect counted more than authority to her, and that is something we would do well to keep in mind. As for turning a convent into a library, well, who could blame her? I’m sure I would do the same! All she wanted was to be left alone with her books – and I love her for it. If you enjoyed this article, consider becoming a patron over on Patreon, supporting my work, and getting access to patrons-only videos. Thank you, and see you next time!

References

Juana Inés de la Cruz, Respuesta a Sor Filotea de la Cruz (1691).

_____, The answer : including a selection of poems (1994).

Christopher R. Egan, “Lyric intelligibility in Sor Juana’s Nahuatl tocotines”, Romance Notes 58 (2018).

Octavio Paz, Sor Juana, Or, The Traps of Faith (1988).

Camilla Townsend, “Sor Juana’s Nahuatl”, Cornucopia, Le Verger – bouquet VIII (2015).