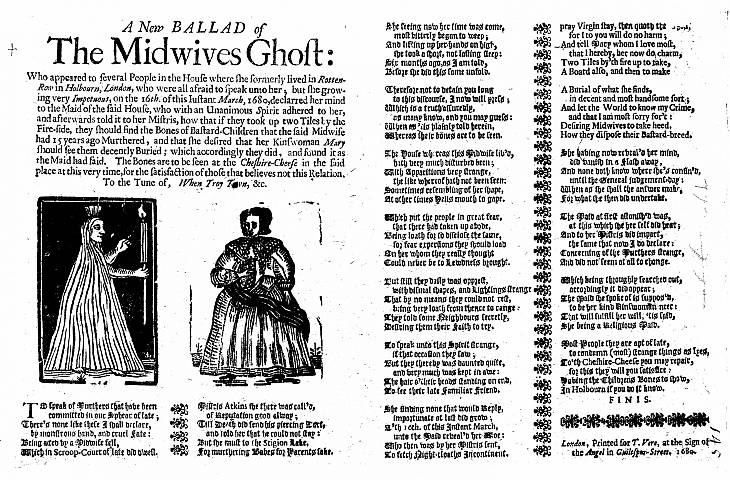

Let me tell you a ghost story. I was reading the book “The Ghost: A Cultural History”, and I was reminded of one of my favourite early modern ballads featuring a ghost. For context, ballads would usually be about current events, and tended to be very sensationalised versions of the news set to familiar melodies. There were lots of ballads in the 17th century about famous murders, and ghosts often appear in them, usually signalling guilt and injustice. Samuel Pepys, the famous diarist, wrote several of them down in his journal, including this one, “A New Ballad of the Midwives Ghost”, which was published in 1680.

The story goes that there was a midwife who lived in Rotten Row (the street name is not a great start, is it?), but anyway, this midwife, Mistris Atkins, lived in Rotten Row, in Holborn, and she had a good reputation throughout her life. But frightening apparitions had been seen at the midwife’s old house after her death, and these apparitions looked like her; plus peoplele heard groans and strange noises. Eventually, neighbours decided to talk to this ghost, although feeling “The hair o’ their heads standing on end, /To see their late Familiar Friend.”

According to the ballad, the ghost confessed her crimes to a maid. The midwife’s ghost tells that she had helped her clients get rid of two unwanted babies by murdering them, and she goes on to explain how she had hidden the bones behind the tiles next to her fireplace. She asks this maid for the remains to be buried properly, and says “And let the World to know my Crime,/ and that I am most sorry for’t:/ Desiring Midwives to take heed,/ How they dispose their Bastard-breed.” Charming. The guilt-stricken ghost then disappears in a flash. In the ballad, these cases of infanticide are described as being committed by a “monstrous hand”, and it is expected that there will be scepticism about this fantastical tale. The ballad goes: “Most People they are apt of late,/ to condemn (most) strange things as lyes,/ To’th Cheshire-Cheese you may repair,/ for this they will you satisfice:/ Having the Childrens Bones to show,/ In Holbourn if you do it know.”

So, the story goes, the bones were taken to a public house, the Cheshire Cheese, as evidence of the murders to those who didn’t believe the ghost story. This pub was on Fleet Street, where most of London’s publishing houses were, which must have helped with sales of this broadside pamphlet. The Cheshire Cheese still operates as a pub today, by the way, and it is one of the coolest, most haunted pubs in London – and I definitely recommend checking it out, especially over Halloween.

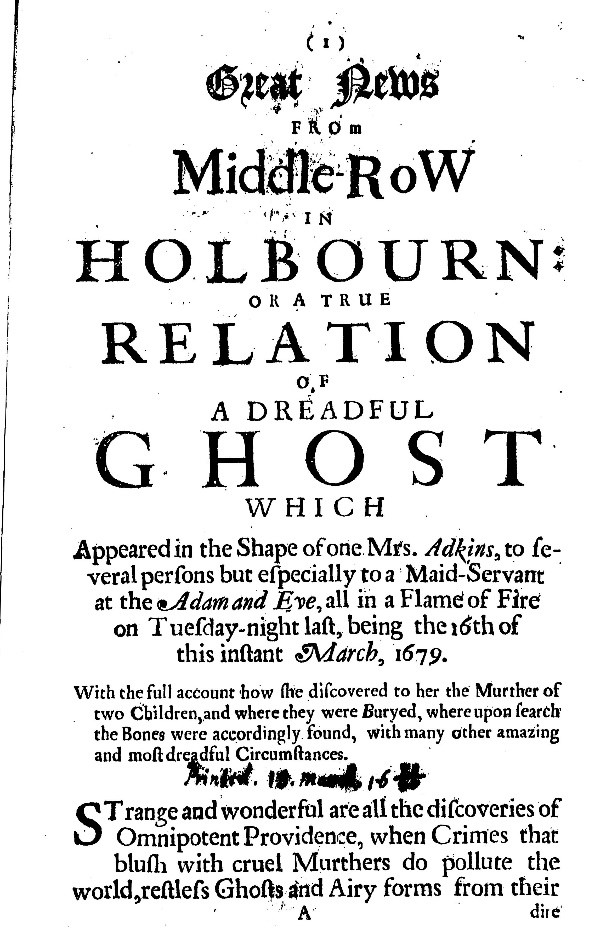

The midwife’s story is sensational and horrifying – and this ballad sold very well. It was sung in alehouses, and the story spread. But is it a true story? Well, many ballads were created about real cases, but many stories were made up, too, or at least heavily embellished to sell more copies. I did find another source about this case, a pamphlet from the year before, called “A true relation of a dreadful ghost which appeared in the shape of one Mrs. Adkins to several persons”. So, I would imagine that the pamphlet inspired the ballad. In any case though, there were many stories like these told in ballads, and they point to an anxiety about the role midwives played in the community in this period.

Men, such as surgeons and man-midwives, were gradually starting to get involved in the world of childbirth, but the birth room was still largely the domain of women. Midwives were both respected in their communities and sometimes regarded with suspicion. Their knowledge about the “secrets of women” gave them power and scared some people: they could potentially help induce abortions, prevent pregnancies, or even, as in this story, be involved in infanticide. At the same time, they were often called to testify in court, as “experts” on the world of reproduction. They occupied a contested space in early modern British society. So, whether the story of these murders is real or not, this ballad’s success indicates how early modern people regarded midwives with ambivalence. They brought new life to this world, but what if they did the opposite, too? The same can be said about “unnatural mothers”, who committed this crime. This story suggests that we would do well to keep an eye out and not to trust midwives, or indeed women, too much.

In the ballad, justice is ultimately restored, and the ghost, it is implied, is paying for her sins in hell. The story is, therefore, reassuring: evil will be punished. If you would like to listen to this ballad, rest assured that I won’t make you listen to me singing. I recommend checking out the recording available on the English Broadside Ballad Archive. And Happy Halloween!

References

Great news from Middle-Row in Holbourn, or, A true relation of a dreadful ghost which appeared in the shape of one Mrs. Adkins to several persons, but especially to a maid-servant at the Adam and Eve, all in a flame of fire on Tuesday-night last, being the 16th of this instant March (London, 1679).

A New BALLAD of / The Midwives Ghost (London, 1680).

Patricia Fumerton, Anita Guerrini, Ballads and Broadsides in Britain, 1500-1800 (London, 2016)

Piers Mucklejohn, “Rationalising a 17th-Century Ghost Story”, Early Modern Scribbling (October, 2021)

Susan Owens, The Ghost: A Cultural History (2017)