In 1503, in the quiet Swiss village of Ettiswil, a woman’s corpse was laid out in the churchyard. Her name was Margaretha, and she had died suddenly; too suddenly, some whispered. Her husband, Hans Spiess, had fled the town, but he was eventually tracked down and brought back to face justice. Justice, however, didn’t mean what we might expect. Spiess was brought before a public crowd, led by magistrates and clergy, and made to stand over his wife’s body, which was laid out on a bier, a wooden platform used to carry the dead. (That’s bier with an “i-e,” not the drink, although one suspects the onlookers may have needed one afterward.). Then came the key moment: he was ordered to touch her corpse.

According to the chronicler Diebold Schilling, as soon as his hand made contact with his wife’s body, blood poured from her mouth and chest, soaking her white shroud in red. The spectators gasped. This wasn’t just a grisly spectacle; it was a sign. In the eyes of the people, the corpse had just spoken. And what it said was clear: This is my killer. Spiess confessed. He was later sentenced to death and executed by breaking on the wheel.

This was a bier-ordeal – a practice rooted in the belief that a corpse would bleed in the presence of the murderer. Known in Latin as cruentatio, from cruentare, to make bloody, the ritual was both a spiritual drama and a form of forensic testimony. It gave the dead the last word. Today, we would probably have a hard time understanding this as definitive evidence. But to the people of Ettiswil, and many others across medieval and early modern Europe, this practice was believed to reveal the truth. It was part of a long and strange history in which bodies were believed to testify – not metaphorically, but physically – against those who had wronged them, based on a widespread, deeply held belief: that a murdered body would bleed in the presence of its murderer.

Part 1: The Divine Witness: Why Did People Believe This?

To understand cruentation, we need to begin with blood. To understand why people believed corpses could bleed like this, we have to step into a different way of thinking about bodies, death, and truth; a world where the line between divine and physical signs was very thin. In Christian thought, blood carried more than life – it carried meaning. It could bear witness, signal injustice, and act as a moral force. The foundational text was Genesis. After Cain murders Abel, God declares: “The voice of thy brother’s blood cries out to me from the ground.” Not metaphorically. Literally. Blood speaks, and God listens. This belief that blood retains moral agency helped shape medieval and early modern responses to violence. Murder disrupted more than human law – it offended divine order. In that view, the physical remains of the victim could manifest the truth that earthly systems failed to uncover.

This theological logic underpinned cruentation. The ritual emerged from a wider belief that God might reveal hidden crimes through miraculous signs. When a corpse bled in the presence of a suspected killer, many understood it as divine testimony. The wound reopened, and with it, the truth emerged. Cruentation also drew on the logic of older ordeals. If God could use boiling water or hot iron to expose lies, why not blood? The Church often found these rituals troubling, though. The Fourth Lateran Council in 1215 forbade clergy from participating, partly to curb the expectation that God would reliably perform on cue. The concern was theological: you couldn’t summon God’s power like a courtroom trick.Official bans slowed the practice but couldn’t erase the underlying belief. Cruentation survived, especially in Germanic and Slavic regions.

That belief shifted into folklore and literature. The Nibelungenlied, a German heroic epic from around 1200, includes a dramatic episode where the murdered hero bleeds when his killer draws near. The scene makes guilt visible through the body’s response. Chronicles used the same motif. The 13th-century monk Matthew Paris wrote that when King Henry II died and his estranged son Richard arrived to view the body, “blood immediately gushed from the dead king’s nostrils, as if his blood cried out to God” at Richard’s presence. A posthumous reckoning perhaps, possibly signalling sin unresolved in life. Not every bleeding body pointed to murder. Some suggested divine judgement more broadly, especially when the dead held political or religious weight.

Such stories, whether legend or not, reveal how medieval people interpreted mysterious post-mortem bleeding as a divine sign accusing the guilty. Shakespeare later alludes to this folk belief in Richard III – the dead King Henry VI’s wounds “bleed afresh” when the murderer comes near. The implication must have been clear for contemporary audiences. The bleeding corpse acted as a divine witness, unbound by the limitations of human courts or politics.

That made cruentation a potent resource, especially in cases with no witnesses or confession. Here, a bleeding corpse offered a powerful sense of certainty. The ritual’s function went beyond symbolism; in the eyes of the community, the bleeding body was the moment justice became manifest. It acted as sacred evidence, a direct bridge between earthly ignorance and heavenly truth, exposing the unspoken and making visible what had been hidden — a miracle, but also, a method.

Part 2: The Corpse in the Courtroom and in the Cloister

The bleeding corpse might have begun as divine omen, but over time, it entered the courtroom — or more precisely, the churchyard just outside it. In parts of the Holy Roman Empire, cruentation was practised as what came to be called the Bahrprobe, or bier-right. The accused was brought to the victim’s laid-out body. If blood flowed afresh, it was taken as divine proof of guilt.

This was never standard legal procedure. You won’t find cruentation in the Constitutio Criminalis Carolina, the 1532 criminal code that aimed to standardise Germanic law. It remained outside the formal lawbooks, operating instead through custom, popular expectation, and the symbolic weight of the ritual itself. In practice, the ritual was often used alongside confession and witness testimony – not instead of them. But it could shape perception, pressure the accused, or tip the scales for magistrates looking for divine endorsement.

Denmark under Lutheran rule presents an interesting tension. The practice was officially banned. Lutheran theology was more sceptical of miracles, and early modern legal reformers wanted evidence, not signs. Yet the prohibition was unevenly enforced. Pastors in small towns quietly permitted the ritual to continue. They might not have believed it entirely, but they recognised its social power. If the dead could speak, people wanted to hear.

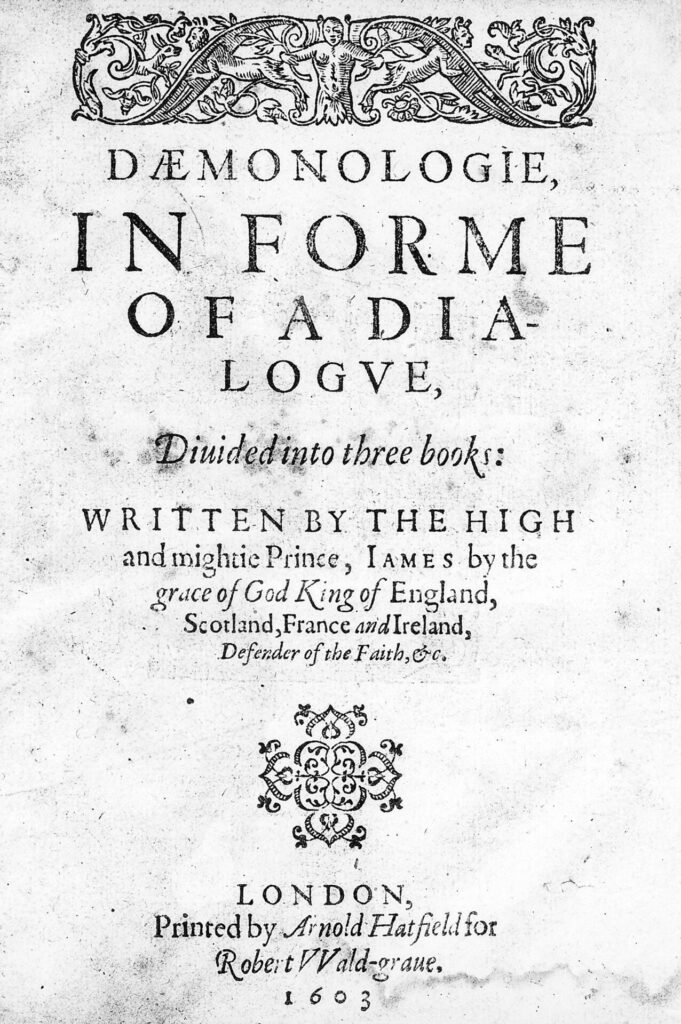

Elite endorsement added weight. In Daemonologie (1597), King James VI of Scotland, who would later become James I of England, described the ritual approvingly: “if the dead carcass be at any time thereafter handled by the murderer, it will gush out of blood, as if the blood were crying to Heaven for revenge… God having appointed that secret supernatural sign for trial of that secret unnatural crime.” This wasn’t idle folklore to him; it was a legitimate means of divine revelation.

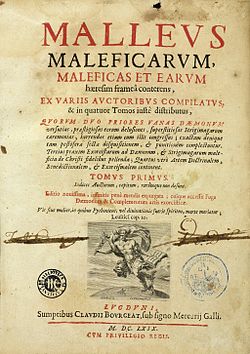

Earlier, the Malleus Maleficarum (1487), the infamous witch-hunting manual, included cruentation as one of many signs of unnatural death. In that context, bleeding corpses did not merely point to individual guilt; they hinted at deeper networks of evil – sorcery, demonic compacts, crimes against the natural order.

Shakespeare picked up on this again in Macbeth, when, after the murder of King Duncan, Lady Macbeth cannot scrub the imagined blood from her hands: “Out, damned spot! … Who would have thought the old man to have had so much blood in him?” , she cries. Her guilt is written in her own mind, but the metaphor echoes the cultural obsession with blood as truth. Her conscience replicates the cruentation logic – the blood returns, the body protests, even if only in her imagination. The stain speaks. The crime won’t stay hidden.

Perhaps the most interesting case from the medieval period was the one recorded around 1260 by the Dominican friar Thomas of Cantimpré, in his encyclopaedic work Bonum universale de apibus. The book is a sprawling mix of theology, natural philosophy, and moral tales, using bees as metaphors for Christian society. Tucked among its pages is an account that’s short but unsettling. Thomas tells of a respected abbot – a man named Henry – who was murdered by his own monks. The motive isn’t given; the crime was secret. There were no witnesses. No one confessed. Until, one day, the corpse spoke. According to Thomas, as the monks stood before the abbot’s body – perhaps in a public procession, or another moment of ritual, I’m not sure – the corpse suddenly began to bleed. Blood flowed visibly, and unmistakably. Faced with this divine accusation, the monks confessed. “The blood cried out,” Thomas writes, echoing Genesis. This was a monastic revelation, blending martyrdom and miracle.

But not all applications of cruentation were so pious. The practice also appeared in antisemitic narratives, especially in the form of blood libel. These were false accusations that Jews had ritually murdered Christian children, often “proven” by signs such as bleeding corpses. The supposed post-mortem bleeding was taken as divine outrage. These accusations led to massacres and expulsions, a dark example of how sacred symbols could be turned into tools of persecution. Cruentation, then, sat in a liminal space: partly theological, partly legal, partly theatrical. It offered communities the sense that justice could be visibly, divinely revealed. And in a world where courts lacked forensic tools and operated amid deep social mistrust, that promise was difficult to let go.

Part 3: Bleeding Bodies and Medical Doubt

By the mid-sixteenth century, Europe was changing. Anatomy theatres were being built, medical faculties were growing, and the body – once a site of miracle – was increasingly becoming a site of study. Europe was still deeply religious, but a new type of thinker was emerging. The anatomist. The legal physician. The man of reason. And to these men, bleeding corpses raised questions. Could blood flow from a corpse without divine intervention? Could wounds re-open naturally? Was cruentation real, or just a misinterpretation of what happens after death?

As early as 1545, the physician Antonius Blancus voiced scepticism. He was no radical, just a careful man with a scalpel who had started to notice that dead bodies did odd things, often without divine prompting. Bleeding, he observed, could happen for all sorts of reasons: the position of the corpse, changes in temperature, even the jostling of transport. The blood wasn’t always resting quietly, waiting for the cue of a murderer’s breath. Cruentation did not vanish overnight, but it found itself more and more under scrutiny. Still, these doubts circulated slowly. The first published refutation of cruentation as forensic proof that I could find appeared in 1669, over a century later. By then, scholars were beginning to describe what we would now call post-mortem physiology. Terms like livor mortis and purge fluid entered the lexicon, not always clearly understood, but pointing to natural explanations for what had previously been considered signs from heaven. If a body was jostled or the chest pressed, this bloody fluid might leak from the nose, mouth, or wounds – possibly giving the illusion of a corpse “bleeding” when handled. Such reasoning attempted to “save” the phenomenon within natural law. The belief in cruentation was a stubborn one.

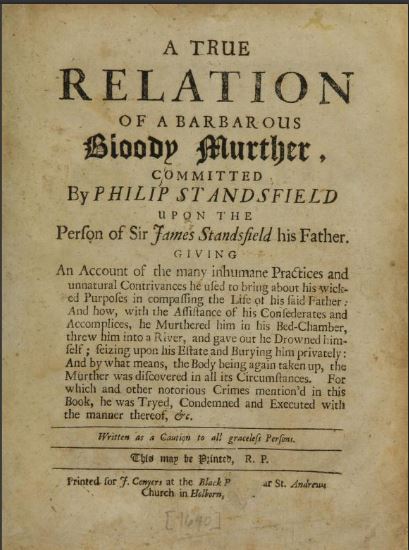

One case stands out as existing between the old belief and the new science: the 1688 trial of Philip Stansfield in Scotland. It was one of the most notorious – and one of the last cases of cruentation in court.Philip stood trial in Edinburgh for the murder of his father, Sir James. The death was suspicious, but evidence was thin. No eyewitness. No clear weapon. But something happened that changed everything. According to the indictment, when Philip helped lift his father’s corpse into the coffin, “the body… did, according to God’s usual method of discovering murder, bleed afresh upon him,” making Philip’s hands bloody. Eyewitnesses said the accused recoiled in terror, and this “portentous sign” of divine justice was presented to the jury. Sir George Mackenzie (the Lord Advocate, nicknamed “Bloody Mackenzie” – I swear I’m not making this up) prosecuted the case and, despite being a learned jurist, emphasised the miracle in court. Philip’s defense protested that this was a superstitious fancy, citing legal scholars who warned such ordeals had led to false accusations. The judges, however, allowed the “evidence”, calling it “a miraculous interposition of Providence”. Philip was convicted and executed for parricide. It was one of the last times that cruentation featured openly in a formal court. A dying gasp of an old belief, still powerful enough to sentence a man to death.

The fact that the debate had reached the courtroom shows how contested the issue had become. For centuries, cruentation had been treated as a kind of sacred intuition. Now it was being forced to justify itself in a world that demanded mechanisms, not miracles.

In 1709, the compendium De miraculis mortuorum, “On the Miracles of the Dead”, devoted nearly 90 pages to bleeding corpses. The very length of the discussion reveals the strain. The author felt compelled to catalogue and defend the phenomenon in detail, which suggests how embattled the belief had become. As late as 1730, the medical-legal treatise Systema Jurisprudentiae Medicae by Michael Alberti still mentioned cruentation among signs of unnatural death. The tone was cautious, but the inclusion mattered. In some circles, the possibility that a bleeding body might still speak remained.

But the Enlightenment had arrived. Anatomists were more interested in circulation than revelation. Jurists were developing evidentiary standards, and judges began to frown at miracles in the witness box. Cruentation didn’t disappear in a blaze of controversy. It faded, slowly, as the assumptions that had sustained it were quietly dismantled. By the early eighteenth century, a bleeding corpse no longer proved murder. It posed a question for the coroner – or, in some cases, an awkward mess for the undertaker.

Conclusion: Speaking Corpses?

Cruentation was never just a belief about bodies. It was a belief about justice; or rather, about the desperate need for certainty in a world full of uncertainty. When the law failed, when witnesses were silent or absent, people turned to the one presence that could not leave the scene: the victim. The bleeding corpse promised that truth would reveal itself. That the victim’s voice, though silenced by violence, would not be buried. In that sense, cruentation was more than ritual. It was reassurance; the hope that moral order could still assert itself when human systems faltered.

And the metaphor has proven remarkably durable. The idea that the body bears witness, that wounds speak, that blood testifies, remains powerful, long after the bier-ordeals disappeared from churchyards. Shakespeare knew it. Lady Macbeth cannot wash away the stain. Richard is exposed not by a court, but by the body he tried to silence.

For centuries, people believed a corpse could name its killer. Not through speech, but through blood – the last, most elemental testimony. Today, cruentation is gone from legal practice. It’s gone from medicine and religion. By the 18th century, it was being dismissed as superstition, bad science, emotional theatre. But it lingered in the popular imagination – in stories, in fears, in literature. Because the idea is potent: that the body remembers and truth cannot be buried. Cruentation isn’t just a relic or a historical curiosity. It was crude, dangerous, and misguided, but it was emotionally powerful. It let people believe that justice could still emerge from silence. If you enjoyed this text, do consider becoming a patron, your support truly means the world to me. Thank you, and see you next time!

References

Anon.,“A True Account of the Trial and Execution of Philip Stansfield” (1688).

R. P. Brittain, “Cruentation: In Legal Medicine and in Literature” Medical History,9(1), 1965, pp. 82–88.

Thomas of Cantimpré Bonum universale de apibus (c. 1260).

King James VI/I, Daemonologie (1597), in modern ed. (Cambridge, 1924).

P. Kost, The Bier-Ordeal of Ettiswil (2006).

A. Nicolotti, “Le metamorfosi del sangue,” in Prove, indizi ed evidenze: percorsi di storia della scienza, (2018), pp. 273–300 .

Matthew Paris, Chronica Majora (entry for 1189).

Irven Resnick, “Cruentation, Medieval Anti-Jewish Polemic, and Ritual Murder”, Antisemitism Studies 3.1 (2019): 95–131.

Diebold Schilling the Elder, Illustrated Chronicle (1503).

Krzysztof Ruszel, “Bahrprobe: Obtaining Evidence in 16th-17th c. Silesian and Moravian legal practice”, Czasopismo Prawno-Historyczne 75(1), 2023, pp. 303–332 . (Open Access PDF)

Francis Watt, The Law’s Lumber Room: Ancient Requisites of English Justice (London, 1893).