Imagine you’re living in Renaissance Florence and you notice you’re losing your hair; maybe you’re a man who’s growing bald, or maybe you’re a woman who’s just given birth. What could you do to treat hair loss? Well, you could use a recipe like this:

‘To prevent hair from falling out: Take dove droppings, burn them, and reduce them to powder, or ash. Make the ash smooth and wash the head with it and it is sure to work.’

Yes, people really did use animal excrements in cosmetic and medical recipes – much more often than you’d think, probably. Weird as they may sound, old remedies using animal excrement – and human urine – were also used to remove marks from the skin and achieve a smooth complexion, probably because the ammonia content in them. Now, I haven’t tried this recipe myself, for what should be obvious reasons. Nor do I suggest any of you attempt the recipes I mention here; sure, using chamomile to attain that sun-kissed blonde look might work, but please stay clear from any formulas using heavy metals or poisons! So, let’s talk about women’s hair and the Italian Renaissance.

Renaissance Beauty Ideals

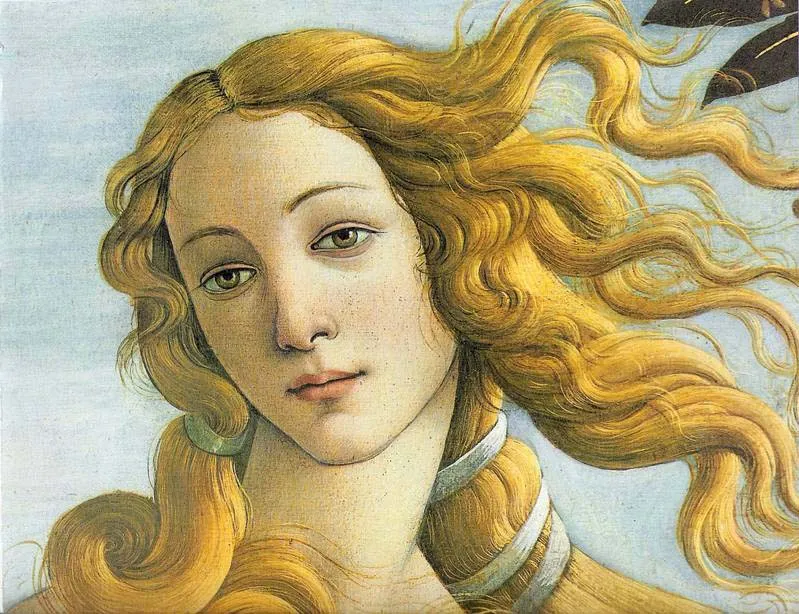

First things first: what did people want from these formulas for hair care? There were plenty of cosmetic recipes published in popular books, from how to dye your hair, to how to make it soft and shiny. As you can tell from the recipe I mentioned, these were not only for women. Still, hair was particularly important if you were a woman, and it was deeply connected to beauty ideals – just think of Botticelli’s Venus with her floating locks! But women were not just mindlessly following recipes to make themselves beautiful for vanity’s sake. Taking care of your hair had much to do with female agency, creativity, and scientific culture, not to mention social expectations. Learning about haircare in this period can give us insights into the history of cosmetics, alchemy, medicine, and hygiene; it can open a window into the world of female sociability and ingenuity. But let’s start with the idea of beauty itself.

Going back a bit, in the medieval period hair was largely considered an expression of female beauty and femininity. Think of how many representations of women show them with beautiful thick braids and curls reaching their knees. Long hair was connected to female sexuality – just think of the 11th-century story of Lady Godiva and how she was literally cloaked in femininity. Of course, there were variations in what was considered attractive and fashionable from place to place and throughout time but, by the Renaissance, women were ruthlessly plucking their hairlines to achieve a high forehead. This is perhaps best illustrated by Elizabeth Woodville, wife of Edward IV, who was considered a beauty. Eyebrows were plucked too so that the face was more ‘delicate’, and hairpieces, veils and coifs all served to accentuate the elongated, oval face. The skin should be pale, ‘dewy as a lily’, and lips and cheeks should have just a hint of pink. This ideal beauty often meant blue eyes too, and blond hair. But not any blond; the shade we would today call strawberry blonde or even sometimes ash. In Italy, the best example of this ideal would be Simonetta Vespucci, the model for Botticelli’s Venus. Oh, the joys of impossible beauty standards! This was a very narrow, clearly-defined, white-centric, kind of beauty; you can see how Titian’s Venus has much in common with Botticelli’s. It was ethereal, fairy-like, by its definition unattainable; the kind of beauty that inspired artists and poets. Petrarch famously descibed his beloved, Laura, having long, curling, beautiful blonde hair, which she wore loose. And yet, even though it was desirable, this beautiful hair could also be dangerous, it could trap men in its metaphorical net as it were. There’s both a fascination and an anxiety around female sexuality and power over men, and I’ll talk a little bit more about the relationship between hair and sexuality in a bit.

In 1562 his book, Gli Ornamenti delle donne, which included over a thousand beauty recipes, Giovanni Marinello described this ideal hair like this:

‘…ancient and modern poets and painters want a beautiful woman’s hair to be long, soft, thick, curled, and of a blond colour resembling gold.’

Of course, most women did not naturally possess this kind of hair. Luckily for them, there were many ways to obtain it by bleaching the hair. There are dozens of recipes for that, more so than any other hair colour, which makes sense if you think that ash or strawberry blonde was considered the ‘ideal’. Women in Venice were famous for their methods. They would apply the bleaching formula to their hair, often made with herbs like chamomile, and they would go to the roof of their houses, to the altana, where they could let the hair dry in the sun. The sunlight was considered crucial to achieve the desired result. But, remember, if being blonde was fashionable, being tanned was definitely not. So, what to do? Well, Venetian women were known to wear a kind of sunhat called a solana, so the name comes from sun, sole. It was a kind of visor; it would protect the face from the sun, but it wouldn’t shade the hair itself, to allow the hair to turn blond in the sunlight.

Beauty secrets like these would circulate orally within families and friends’ circles, and people could write them down in personal or familial recipe books. But they were also available in print. You could buy Giovanventura Rosetti’s 1673 Secreti nobilissimi dell’arte profumatoria and follow the formula ‘To make hair blond like golden threads’ and ‘in very few days, your hair will be like strands of gold’. Renaissance recipe books were domestic manuals, including everything from how to treat worms in horses and make a restorative drink for someone who has a fever, as well as haircare. And that isn’t surprising. Besides besides beauty ideals, taking care of your hair was considered important to your health.

Hygiene and Medicine

Now, you might be wondering what haircare has to do with health. Well, according to the writings of Aristotle and Galen, which were still very influential, hair was a functional part of the body, and it was a physiological signifier of identity, indicating age, gender, and personality. Let me explain. In medical texts, taking care of your hair was often presented as contributing to your humoral balance and hence your overall health and the vitality of the body. In this period, hygiene was deeply connected to medicine in general. I made a video about this in more detail, which I recommend you watch if you’re interested in learning more about the context, but the main issue is that, because it was believed that ‘excrements’ were expelled by the body through the skin pores, it was important to keep the head clean, both the scalp and the hair itself. However, this could be tricky, and doctors disagreed on the best ways to cleanse your hair. Haircare was a question of health, even life and death and so, it was hotly debated, not only by doctors, but by everyone. Women exchanged letters full of advice, including recommendations about whether, how, and when to wash their hair. Medieval writers had mostly seen hairwashing as beneficial for people’s health, and advised it to be done twice a month. However, in the Renaissance, there was much uncertainty and anxiety about it, because washing your hair could be both an important hygienic practice and a challenge for the body.

In most regimens of health, which were basically guides on how to remain healthy, the care of the head and the hair was considered important. In the popular Regimen sanitatis salernitani, it was advised that readers start their day by combing their hair, as it would open the pores of the scalp and so allow vapours caught in the brain from the digestive process to leave the body. Throughout the day, combs would help draw these vapours out through the top of the body. And, if you didn’t have a comb, you could use rough cloths to scrub the head. Some writers believed rubbing the scalp and combing the hair to be safer than washing your hair using water. People were also advised to avoid it if they had a cold, and women were sometimes advised to abstain from hair washing during pregnancy and during their periods, although not everyone agreed. There were even some cases when women miscarried and attributed that to having washed their hair and tiring their bodies, which is so heart-breaking, isn’t it?

Giovanni Marinello, the author of lots of cosmetic recipes I mentioned earlier, suggested that the usual practice should be to wash the hair with warm water once a week and, as for the other days, just comb it mornings and evenings. But how did women wash their hair? Well, in many Italian cities, it could be done by leaning on the floor over a copper basin, wide and shallow, or you could use a table to place the basin, over which you would bend your body. You might do everything yourself, or you might count with the help of a friend or maid, depending on how wealthy you were. Besides warm water, you could use one of the many recipes to prepare hair soap – something similar to our contemporary shampoo -, or you could buy it already made. This hair-washing formula would usually be composed of lye, often produced using ashes, and fragrant powders, made with herbs and flowers. After washing your hair, you could use a special towel to wrap around your head, drying your hair and, crucially, keeping the head warm. Some of these towels still exist in museums like the V&A today, and they’re usually longer and thinner than towels meant for the body. Washing the hair was thought to be risky, and so you should keep your head warm and, ideally, rest afterwards. In her wonderful book, How to be a Renaissance Woman, Professor Jill Burke even mentions how Lucrezia Borgia, who had stunning hair, apparently, would often use the hair-washing excuse to avoid attending events; she would claim she needed to rest afterwards. And I’ll get back to Lucrezia in a bit, as she was accused of copying another noblewoman’s hairstyle – and that’s just unforgivable.

Anyway, according to Dr Castore Durante, one should be cautious when washing the head, even if the operation did comfort the brain. Soaps using specific herbs should be used according to the season and the warm towel was useful to keep the hair from being exposed to cold air. It was preferable to wash the hair in the evening before dining, presumably to avoid sleeping with the hair wet. As you can see, Lucrezia Borgia’s excuses for not socialising would have found support in contemporary medical advice!

Fashion and Courtly Life

But that’s not all. Who knows, maybe Lucrezia Borgia just wanted to spend some time with her female friends instead of attending events at court. Haircare practices could be sociable, creating an occasion for women to cement friendships and negotiate hierarchies as well as fashioning their personas. Haircare and hairstyling were complex and time-consuming, especially if you were wealthy. If you were in the Medici court, for instance, your morning toilette would be concluded by taking care of the hair. You might have a small table with a ‘hairdressing drawer’, for small objects such as scissors, combs, and pins and a mirror, and your maids or friends could comb your hair and curl it using tongs. In the 16th-century, thick curls were very much in, as you can see in Maria de’ Medici’s portrait. People could use hot cloths to create these curls, and hair could be wound around heated metal spoons (another tip by Giovanni Marinello from his book Gli Ornamenti delle donne), which I imagine wouldn’t be too different from our contemporary curling irons. But methods varied widely; in one of the recipes in the Medici archive, for instance, there’s a recipe written by Don Antonio de’ Medici, who collected over six thousand recipes, using tree root oils described as ‘To make the hair curly’. Many of these procedures would be complicated, and a way to indicate how the person with this hairstyle was someone of high social standing, who had the time and the money to spend dying their hair and having it braided, decorated etc.

For women in particular, styling each other’s hair could be an important part of their social lives. It involved female bonding, creativity, and sociability. If you weren’t as wealthy as the Medici, experimenting with hairstyles was much less expensive than buying or making new clothes, too. Not to mention that, if you didn’t like the result, it was usually quite easy to go back to the hairstyle you had before. And, in the worst case scenario, hair would always grow back. So, women experimented. And, often, authorities worried about the corruption of society; about confusion around gender roles when women adopted ‘masculine’ hairstyles, about people from lower ranks adopting styles ‘incompatible’ with their status. Sumptuary laws, essentially legislation created to make sure people behaved appropriately, conforming to their social status, attempted to control hairstyles and to enforce ‘morals’. In many Italian cities, certain hairstyles were subject to restrictions, with people risking fines, in the same way that rich fabrics worn by aspiring merchants or generous cleavages were policed. Still, it was hard to deter people from experimenting with hairstyles and sumptuary laws ultimately failed to regulate how people wore their hair and make it conform to their social class.

In the 17th century, wigs and hairpieces started to become more popular, and this trend spread from Italy to other places, especially France, in the 1660s. Of course, your budget determined what you would get, and these hairpieces could vary. Many of the most expensive ones were bequeathed to friends and family in wills. If you were wealthy, you would probably buy hair from young women living in poverty, in your choice of colour and texture. Blonde tresses tended to be more expensive than darker ones.These hairpieces typical of the elites would mark a physical subbordination of poorer people. If your budget was slightly less generous, you might buy something made from hair taken from deceased people, usually poor. If you couldn’t afford that, you might go for cheap hairpieces, made with sheep or goats wool, or horsehair, or even straw. I know that might sound strange, but in many cases, these pieces were used just like our contemporary hair extensions are today to sort of ‘bulk up’ your hairdo. They might buy just a few braids to achieve a more voluminous hairstyle, for instance. Going back to the business-savvy Medici family, Cosimo III de’ Medici even came up with a yearly tax in 1692 for anyone who wanted to wear a wig. Some cities just forbade them, but why do so if you could just make some money instead?

Hair could be political. And, in a time in which women’s voices were highly restricted in the public sphere, they might be a way to signal loyalty and allegiance, not to mention belonging, as in the case of Eleonora di Toledo when she arrived at the Medici court. Or Anne Boleyn popularising the French hood in Tudor England. Isabella d’Este, an incredible alchemist and patron of the arts, was well-known for creating new ways of styling her hair, and it was said that she was furious when others copied them – apparently, that was the case of Lucrezia Borgia and her ladies, and it caused quite a scandal. That might sound like a small matter, even petty. But this was a time in which women had a very limited level of agency and control over their lives. Taking care of each other’s hair and coming up with new ways of changing hair colour, making hair smooth or curly, and styling it, were all ways for them to bond, but also to share their individuality and creativity and to explore the world of scientific experimentation, such as using alchemy and distillation to attain just the perfect shade of blonde. And women’s hair was crucial to how they would be perceived, especially by the opposite sex.

Hair and Sexuality

There’s another important aspect to hair, of course. In many cultures, hair, and especially female hair, is linked to sexuality. It can be a symbol of femininity and sexuality; hair can be ‘erotically charged’. This can be seen in many cultures across the globe and, even though today most people would associate hair coverings and veils with Islamic cultures, they were common in medieval and early modern Europe, when most people would have their hair covered with some kind of headwear. For men, this could mark social status and political power, while for women, it could determine their social role, with hairstyles changing when their social place changed, too. Long hair was a ‘female glory’, but it shouldn’t be visible to everyone and one of the reasons for that was probably this connection between hair and female sexuality. It’s perhaps unsurprising that, in the Renaissance, nuns usually had their hair shaved off when they joined a convent, and were instructed to keep it short, a practice which survived through the centuries. Long and luscious hair wouldn’t be appropriate for the brides of Christ. This marked their transition to a religious life, with the veil covering their heads after joining the convent. But hair was symbolic for laywomen, too and hairstyles often varied according to age and life stages.

And here we get to one of my – admittedly numerous – pet peeves when watching period dramas. Because we tend to find many of the veils, coifs, bonnets and hairstyles women wore in the past unattractive, costume designers tend to let characters run free with their flying locks. Just think of Emma Watson’s beach waves in Little Women or, even worse, Jane Austen adaptations, without a bonnet in sight. Yes, I love Keira Knightley, but where’s her bonnet?! The most recent version of Emma with Anya Taylor-Joy is a notable exception and one of my favourite examples of costume design done right. But I digress. In the Renaissance, young girls would often wear their hair loose. But, when puberty hit, it was common for hair to be up, often braided, and covered when out in public. It was very rarely just allowed to be worn loose. How much you should cover your hair and in which style depended on fashion, of course. It could be styled with all kinds of accessories, such as ribbons and pins, brooches and nets, depending on social status and wealth. But simply plaiting and then pinning the hair in a circle at the back of the head with the front parted in the centre, framing the face, was very common. And this style was often covered by a coif. What’s interesting is that, when you think of period dramas, they often get maids’ hairstyles right. Princesses and queens, on the other hand… Oh well, I promise I won’t start talking about Reign and their Coachella-inspired hairstyles.

In any case, and I know I’m generalising here, but roughly, the more hair you showed, the more sexually available you were assumed to be; availability for marriage could often be deduced based on how a young woman wore her hair, which changed when they reached a ‘marriageable’ age. When women got married, going from maids to wives, it was often expected for them to wear their hair up, usually covered with a coif, veil, or headpiece of some sort. This indicated their submission to their husbands, and their place in the family and the community. Married women wouldn’t cut their hair short like nuns would, but there was often a social expectation for their heads to be covered, as they weren’t ‘sexually available’ anymore – except for their husbands.

And this is important. You see, in these Renaissance recipe books I mentioned, with their medical formulas, culinary recipes, and general tips on how to manage domestic life, including things like removing stains from clothes and how to make soap, it would make sense to include cosmetic recipes, such as how to keep hair smooth, shiny, or make it blond. Beauty remained important after a woman was married; it was arguably part of her wifely duties. Taking care of her appearance, along with fulfilling the ‘marital debt’, so, regularly having sex with her husband, was often considered a wife’s job, to keep her husband from… let’s say straying. So it is a bit misleading when we think of women in this period (or any period, really) as being vain and frivolous, worrying about their beauty just for the sake of it, just for their own pleasure. For most women, across social divides, taking care of the family’s health and hygiene, managing the house and its animals, along with cleanliness and cookery, were all domestic duties, even if the woman in question had maids. And so, a commitment to beauty and haircare could be understood as a household duty too. It was socially expected, and so it’s no wonder that these eclectic recipe books, which were essentially guides to be used in the home, would also include cosmetics.

Cultural Hair Codes

Remember that in the Renaissance one of the main ways of understanding the body was through the humoral theory, so the belief that everyone had four humours, black and yellow bile, phlegm, and blood, that their balance determined health, but also, that the individual complexion – both physical and what we would today call psychological – was determined by this humoral composition. The Roman physician Galen (129-c. 216) had been particularly interested in physiognomy, the ‘science’ which associated someone’s physical appearance to their internal qualities, from their character to their intelligence, and it’s possible that he was influenced by a popular book at the time, De Physiognomonia, by Polemo of Laodicea. In any case, if you’re interested in history I’m sure you know how this pseudoscience has been used throughout history in horrific ways, especially in the late 19th and early 20th centuries to justify racism and to popularise eugenics. In any case, what Galen did in ancient Rome was to combine physiognomy and the humoral theory. And, many centuries later, in the Italian Renaissance, physiognomy became popular again, in no small measure thanks to humanists like Giambattista Della Porta. I mentioned him before on this channel, he’s the Neapolitan magus who published a recipe for a flying ointment given to him by a witch, allegedly, and for which he got in trouble with the Inquisition.

In any case, through Galen and, later, people like Della Porta, these associations between humoral complexion and appearance became widely discussed. So, in the Renaissance, these theories linking appearance and character gained new life, with physiognomy guides and portrait-books becoming popular. And here we get back to hair. The four main complexions were linked to the predominance of to each of the four humours. These ‘personalities’ could be sanguineous, in which blood predominated, so they were cheerful, happy, and full of life, with rosy cheeks and blonde hair; choleric, in whom yellow bile predominated, and so they were energetic and prone to anger, and would likely have reddish hair. Phlegmatics were determined by phlegm, so they were believed to be calm people, often with brown hair. Finally, the melancholy personality, caused by an excess of black bile, meant that these people tended to worry and feel ‘depressed’, and they were usually believed to have darker skin and hair.

Hair had meaning; its colour and texture could be used to determine someone’s humoral balance and, consequently, what we would today call their personality. Again, this was a time in which humanists took physiognomy seriously and so they would write how women with curly hair were timid, how platinum blond hair hinted at ignorance or stupidity, black hair could denote a cunning character and, of course, the ideal, ‘golden hair’ for women made them pleasant and, in men, it made them strong, arguably the central attributes of each gender. These associations have some serious sexist and racist undertones, of course, and they varied from place to place and across time. In ancient Greece, for instance, high-class prostitutes would bleach their hair blond with herbal dyes, and Roman prostitutes would sometimes wear blond wigs, as the colour was associated with lust.

And, although that changed in the medieval and early modern periods, with many saints being depicted as blondes, as well as many pious princesses and queens, it’s hard not to notice that, in depictions of Eve, the original sinner in the Bible, she is often shown with blond hair. And, contrary to Lady Godiva, her hair rarely conceals her body. In Milton’s Paradise Lost, published in 1667, Eve has ‘unadorned golden tresses’ which lie in ‘wanton ringlets’, maybe alluding to the serpent. On the other hand, the Virgin Mary is usually depicted as a brunette, or at least a dark blonde. And, of course, her body is modestly covered, except when she’s breastfeeding the baby Jesus. So you can see how all these symbolic aspects of hair are intertwined. As for red hair, symbolic associations have varied widely, but, following the choleric personality, it could be associated with an excess of heat, denoting fiery, intense people. It’s perhaps not surprising that the Roman historian Cassius Dio (c. 165 – c. 235) would describe the brave ancient British queen Boudicca as having flaming red hair. But red hair had also long been associated with untrustworthiness. In his History of Animals, Aristotle had described red-haired men as envious and proud. According to him, red hair indicated pride, ignorance, and betrayal. Who knows, maybe in describing the enemy Boudicca as red-haired, Cassius Dio was hinting at this.

Crucially, while a person’s hair was believed to come from the body’s humoral constitution, with hair physically indicating their character and identity, it was also something that could be changed. It could be styled, cut, coloured, according to fashion and cultural beliefs about beuaty, morality, and social order. So, with all these changing associations, not to mention concerns about health and attracting/keeping a husband, is it any wonder that women would be interested in haircare recipes?

Haircare Recipes

We have plenty of evidence that people took care of their hair at home, from ridding the scalp of pests to dying the hair to a fashionable colour. Take a look at the table of contents in this 16th century recipe book, a best-seller attributed to a mysterious lady, Isabella Cortese, promising to tell readers all about the secrets of the world of alchemy, medicine, and cosmetics. There are over twenty recipes about hair, most of them for dying it. In the 16th and 17th centuries, virtually every recipe book published would include recipes to make hair shiny and beautiful, to change its colour, and to treat hair loss, like the lovely pigeon dropping recipe I started this text with.

Going back to the beauty ideals I mentioned earlier, the most fashionable hair colour for women was an ashy blonde. The recipes themselves varied widely – authors and publishers were aware that their readers would have different skill levels and budgets, and so they tended to offer several ways of attaining the same goal. But many of these recipes were a mix of caustic substances and vegetable dyes. A common way of lightening your hair was to wet it using a sponge, with a mix of sulphur, rock alum or wax, and honey. After that, you would let the hair dry in the sun. This is one of the manuscript recipes in the Medici collection:

‘Water to make the hair blond: Take 6 ounces of black sulphur, 2 pounds of rough alum sediment and 4 ounces of good honey. Mix together well and distill carefully to obtain a precious water which gives good results when it is rinsed, and when you want to use it take a sponge and wet your hair with it, then let your hair dry in the sun.’

If you had dark hair, but it was starting to turn grey with age, recipes using figs and walnut husks to dye it back were recommended, and it was noted that this would work for eyebrows and beards, too, so it was clearly a recipe meant for men, as well. And, besides the dove droppings recipe I mentioned, many other recipes for treating hairloss would be fat-based, which could close the pores in the scalp. According to Don Antonio de’ Medici, who collected many of these recipes, baldness was caused by excessive heat in the body. According to the humoral theory, men tended to be drier and hotter than women, in whom wet and cold humours predominated. This explained why it was usually men who lost their hair. The problem was exacerbated by eating certain ‘hot’ foods that would create an excess of warm humours in the brain – and if you’re interested in this connection between food and medicine, I suggest checking out my video on this topic. These men should avoid this category of ‘hot’ foods: onions, garlic, and leeks, for instance. They should stay away from wine and hot baths, which were believed to make the body even hotter. And, Don Antonio writes, they should not ‘make love too often’ as that too, would warm the body excessively.

Women, on the other hand, were advised against ‘excessive bodily hair’ which could make them ‘masculine’. Even if we’re thinking just of the face, achieving the delicate eyebrows and high forehead look could mean using the caustic effect of some ingredients to accomplish that goal, too. So, the same rock alum that you might have used in a recipe to become blonde could be used in another one to remove unwanted hair. Tweezers and adhesive resins could be used too.

If you were happy with your hair colour and texture, and you considered it shiny enough, you still had hygiene to consider. How would you keep it clean? As I mentioned, people did wash their hair with water, using lotions, or what we would today call ‘shampoos’. The basic composition would be a water-based formula using plant ashes, such as from vine, which would produce lye when mixed with fats. Olive oil was widely used in Mediterranean areas, but in other parts of Europe animal fat was more common. Herbs and other ingredients could be added depending on the effect you wanted: for long hair, honey and eggs would keep it smooth, chamomile and sage were recommended if you wanted your hair to be softer, for thicker hair, mallow or wild pumpkin could be advised etc. There were also recipes for ‘rinses’, similar to our contemporary conditioners. Which makes sense when you think of just how long hair could be and how tricky it might be to untangle it! So these formulas aimed to make the hair straight and sleek, and tended to involve olive oil, often scented with roses.

But there were other ways to keep your hair clean, too. How you would cleanse your hair and scalp depended on the season and your health, and so it was important to have an alternative to water. Recipes for what we would today call ‘dry shampoo’ were very popular, too, along with the washes and lotions that people would use if they were cleaning their hair with water. You could buy these readymade, but many people made these ‘dry shampoos’ or powders at home. Perhaps the most famous was the ‘Cyperus powder’, later called ‘French powder’. It was a very popular recipe in the 16th century and it became even more well-known in the 17th century, often called ‘the queen of cosmetics’. The name of the formula derived from cyperus, a tuber from the Mediterranean. And this powder was used for lots of different things. It was scented, and so it was used to perfume linens. When wigs became fashionable, this powder was used a coating for wigs as well as hair, but it could also perfume the face and hands. You could apply it using bellows or, later, powder puffs. People were advised to rub the hair with a towel first, and to do so vigourously – probably to open the skin pores. After the powder had been applied, some kind of head covering should be worn to sleep and, in the morning, you could just comb your hair for a fresh look. The powder was known to make the hair fragrant and soft. Again, how similar does this all sound to today’s dry shampoo? But, of course, this wasn’t just about utility. This powder became a beauty accessory, a visible and aromatic marker of wealth and social standing. It became so popular at court that not using it would arguably be a sign that you didn’t belong.

Final Thoughts

As you can see, there was much going on in the world of Renaissance haircare; hair marked distinctions of gender, age, class and race. It could be a way of policing people according to social norms. In women’s case, their hair could indicate gendered subordination, signal their faith, highlight their modesty and, of course, mark their wealth and social rank. But of course, you could also argue that because people could conform to social expectations through hair, this also meant that this association between hair and identity was constructed, and how it could be altered. And so, hair was used to conform but also to disrupt social norms. Hair that was worn completely loose, ‘uncontrolled’ as it were, was often associated with people in the margins, outside of social control: criminals, witches, prostitutes, and those considered ‘mad’. Hair carried a lot of meaning, and hair care could be a tool for people to control not only their appearance, but also how the representation of their inner self to society.

You can also tell how hair was connected to the worlds of cosmetics, medicine and hygiene, alchemy and experimentation, but also to courtly life and social rituals and especially female sociability and creativity! The world of cosmetics really offers a unique insight into all of this. And I haven’t explored the connection between hair and magic, or combs being exchanged as love tokens, nor did I mention skincare, which could be another text in itself. But just take make-up using lead to make the face whiter. The wealthier you were, the more ‘pure’ the formula would be, so containing higher levels of lead. And, the more lead there was, the more hair loss there would be too, with eyebrows and hairlines suffering and so, even more cosmetics would be needed, including recipes to make hair grow back. Not to mention that people would literally die from lead poisoning.

But you know what I mean. And for this text I mainly focused on women and the Italian cities. As professor Jill Burke writes in her book, How to be a Renaissance Woman, hair and haircare was one of the few areas in this period over which women could have agency and control. They could use hair to express themselves, their individuality and their loyalty, but they could also experiment with cosmetics, and this experimentation undoubtedly played a role in what would later be called the ‘scientific revolution’. And many of this recipes and much of this knowledge has survived to our days, sometimes relegated to the domain of superstition and ‘old wives tales’. It’s still said in Italy that you shouldn’t leave the house with your hair wet, for instance. Luckily, no one seems to be recommending any recipes with animal excrements for hair loss anymore.

(All translations of primary sources are my own.)

Primary Sources:

Aristotle, Historia Animalium (1965).

Galen of Pergamum, ‘The Best Doctor is Also a Philosopher’, in Galen: Selected Works, trans.by P. N. Singer (1997).

Isabella Cortese, I Secreti (1565).

Castore Durante, Il tesoro della sanità (1586).

Di Levino Lennio, Della complessione del corpo humano (1564)

Giovanni Marinello, Gli Ornamenti delle donne (1562).

Giuseppe Rosaccio, Avvertimenti a tutti quelli che desiderano regolatamente vivere (1594).

Giovanventura Rosetti, Secreti nobilissimi dell’arte profumatoria (1673).

Arnaldus de Villanova, Regimen sanitatis Salernitanum (ca. 1500).

Apparato della Fonderia dell’Illustrissimo et eccellentissimo Signor Don Antonio Medici (BNCF, Magl. cl. XVI, n. 63, vol. IV, 1604).

Ricettario 2680 (Florence, Biblioteca Riccardiana, ca. 1622).

Further Reading:

Jill Burke, How to be a Renaissance Woman: The Untold History of Beauty and Female Creativity (2023).

Sandra Cavallo and Tessa Storey, Healthy Living in Late Renaissance Italy (2013).

Richard Corson, Fashions in Hair: The First Five Thousand Years (1965).

Stephen Dobranski, ‘Clustering and Curling Locks: The Matter of Hair in Paradise Lost‘, PMLA 125(2), 2010, pp. 337-53.

Sarah Jane Downing, Beauty and Cosmetics (1550-1950) (2012).

Valentina Fornaciai, ‘Toilette’, Perfumes and Make-Up at the Medici Court (2007).

Giovanna Hedesan, ‘Alchemy and Paracelsianism at the Casino di San Marco in Florence: An Examination of La fonderia dell’Ill.mo et Ecc.mo Signor Don Antonio de’ Medici (1604)’, Nuncius 37 (2022), pp. 119-143.

Farah Karim-Cooper, Cosmetics in Shakespearean and Renaissance Drama (2006).

Julia Martins, ‘Follow what I say’: Isabella Cortese and Early Modern Female Alchemists (2022).

Meredith Ray, Daughters of Alchemy: Women and Scientific Culture in Early Modern Italy (2015).

Edith Snook, A Cultural History of Hair in the Renaissance (2021).

Evelyn Welch, ‘Art of the Edge: Hair and Hands in Renaissance Italy’, Renaissance Studies 23(3), 2008, pp. 241-68.

_______, ‘Signs of Faith: The Political and Social Identity of Hair in Renaissance Italy’, in La fiducia secondo i linguaggi del potere, ed. by P. Prodi (2008), pp. 371-86.