When I was growing up, my grandmother told me to avoid cold showers if I was having my period. I was also not supposed to leave the house with my hair wet unless it was summer. When we travelled to the mountains, my other grandmother would ‘fill her lungs with forest air’. She claimed to feel instantly healthier. I’m sure …

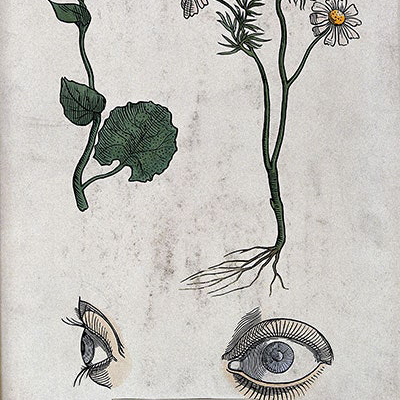

What is the ‘Doctrine of Signatures’?

In the early modern period, an impotent man might be prescribed boiled orchid roots. But why? Well, they resembled testicles and were consequentially believed to be useful in improving male potency. If you think this sounds weird, stay with me. Efficacy aside, prescribing this remedy makes sense… if you accept the premise of the doctrine of signatures, one of the …

What is the ‘Wandering Womb’?

Imagine ‘an animal inside an animal’, a thirsty creature, dragging itself in search of water, pushing aside everything that was on its way… Do you think that sounds sinister? So do I.

What are the ‘Non-Naturals’?

When I was growing up, I was told to avoid cold showers if I was having my period. I was also not supposed to leave the house with my hair wet unless it was summer. When we travelled to the mountains, my maternal grandmother would ‘fill her lungs with forest air’. She claimed to feel instantly healthier.

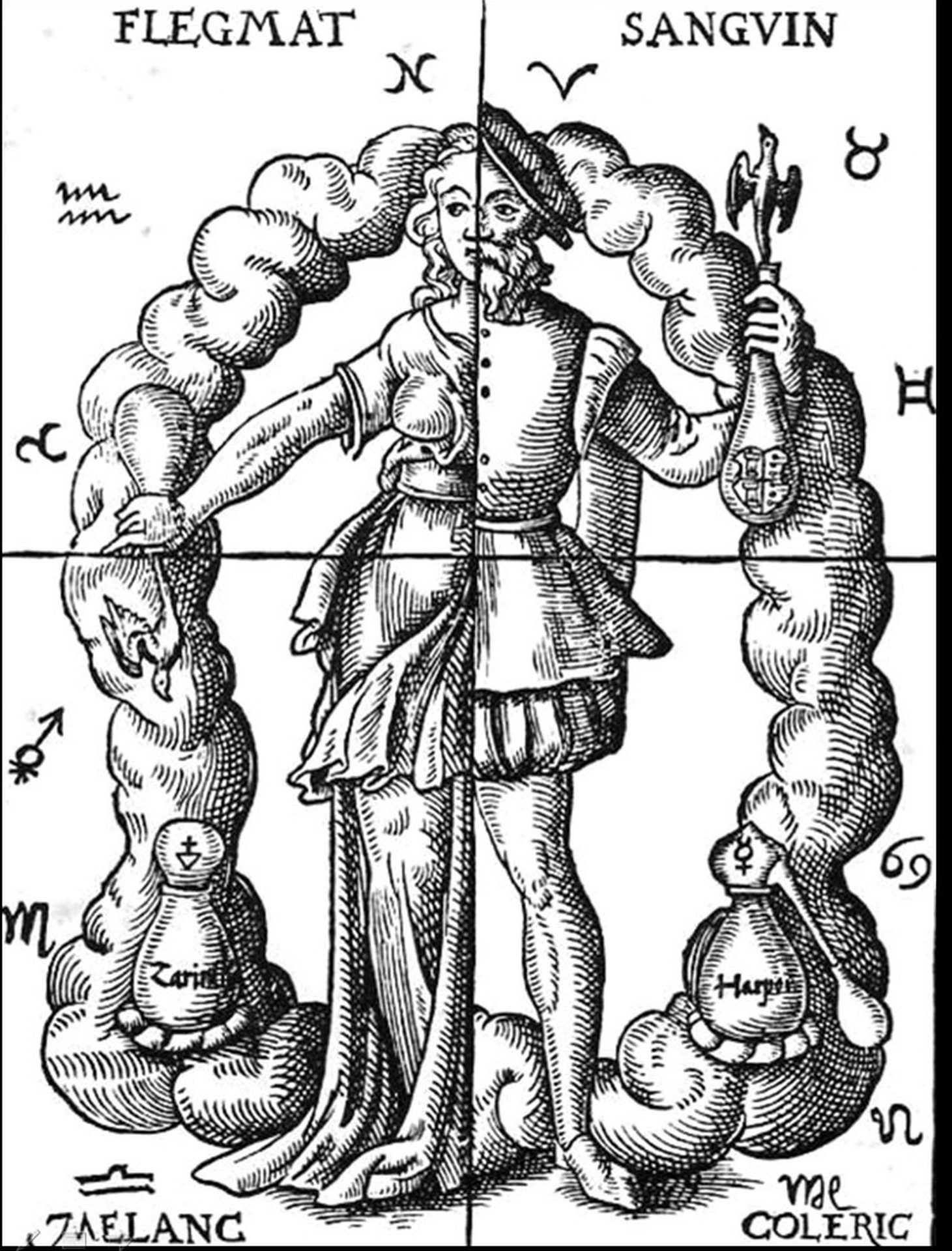

What is the Humoral Theory?

Humours are everywhere. People can react cholerically to an insult, music can make us melancholic, time with friends can lift our spirits, and we can be in good or bad humour. This is not surprising. The humoral theory has a long history, beginning with the Greek Hippocratic writers in the fifth century BC, being reinterpreted by the Roman physician Galen in the second century AD.

What is Gender History?

In the 1920s, Virginia Woolf famously described how the history of women was unknown: ‘It has been common knowledge for ages that women exist, bear children, have no beards, and seldom go bald, but save in these respects […] we know little of them and have little evidence upon which to base our conclusions.’ Woolf was writing shortly after women were granted the vote in the UK (1918), after an arduous campaign by the suffragettes. This first feminist wave, associated with the political women’s suffrage movement, did not prompt historians to investigate women’s history with a few exceptions.

What is Cultural History?

Cultural history is not the history of culture – whether we think of culture in a strict sense (high culture…

What are Secrets of Women?

Throughout history, the womb was often thought to be a mysterious organ, which could make women ill yet create new life. Knowledge about women’s bodies and especially reproduction was thought to be hidden in the womb, ‘secret’ from prying eyes.