In the early modern period, an impotent man might be prescribed boiled orchid roots. But why? Well, they resembled testicles and were consequentially believed to be useful in improving male potency. If you think this sounds weird, stay with me. Efficacy aside, prescribing this remedy makes sense… if you accept the premise of the doctrine of signatures, one of the most influential ideas in the history of medicine. But what exactly was it?

Origins, Development, and Principles of the Doctrine of Signatures

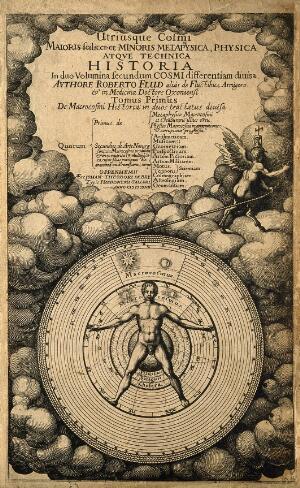

The doctrine of signatures was a way of understanding the world based on analogy and symbolic thinking. In Greek antiquity, Pythagoras (c. 570 – c. 495 BC) had described nature as ruling both the macrocosm and the microcosm. Humans mirrored in their bodies (the ‘microcosm’) the larger world around them (the ‘macrocosm’). Blood brought life to the body, just like water streams did to the land, while bones were like rocks. Hippocratic writers developed this idea, as did later Neoplatonists. If the world was composed of a network of correspondences, that gave people clues about how best to treat the body when it fell ill. (Hence the orchid root treatment mentioned above.)

Being a part of nature, the perfect remedy could be found by those who knew how to ‘read the book of nature’, that is, understand the hidden signs and clues that indicated which plants (though animal and mineral medicines were used as well) could help treat the issue, based on their shape, texture, colour, or smell. So, just like the testicle-looking orchid roots, the phallic roots of mandrake could also be indicated to treat fertility issues in men. (You can read more about early modern aphrodisiacs and fertility here.)

Connections to Medical Practices and Theories

Renaissance scholars, including Paracelsus (1493-1541) and Giambattista Della Porta (1538-1615) developed this theory in their works, describing how all natural things corresponded and dialogued through this network of hidden meanings. Renaissance writers reconciled the doctrine of signatures with Christianism: it had been God, in his wisdom and power, who had decided to fill the Earth with medicines to treat all ailments. Benevolently, he had indicated the therapeutic value of plants through their appearance, with exterior signs. It was up to humans to investigate and find out cures, through observation and experimentation.

This principle was eventually called ‘doctrine of signatures’ following the publication of The Signature of All Things in 1621, by Jakob Boehme (1575-1624), in which he articulated the belief in this network of natural beings. For people like Della Porta, who described himself as a ‘magus’, ‘natural magic’ was largely dependent on understanding these relationships and making use of them to transform nature, creating ‘wonderful and miraculous things’. The doctrine of signatures allowed people to understand the governing principles of the universe, from the minuscule hair strand to the majestic sun and the planets. Astrological medicine was closely connected to the doctrine of signatures (and I will write about ‘zodiac man’ some other time!).

Applying the doctrine of signatures to medical practice was linked to sympathetic magic as well, and the medical idea that ‘like cures like’ (similia similibus curantur) through sympathy or affinity. However, although these theoretical concepts emerged from learned writers and influenced popular practice, they were also influenced by empirical knowledge and the practice of ‘traditional’ healers. Early modern medicine was a mix of many different traditions from myriad sources, which sometimes contradicted each other, and which could be adapted to different contexts and individual cases. For Nicholas Culpepper (1616-1654), who wrote in the vernacular for a wide readership, the doctrine of signatures was essential for all those hoping to take care of their health.

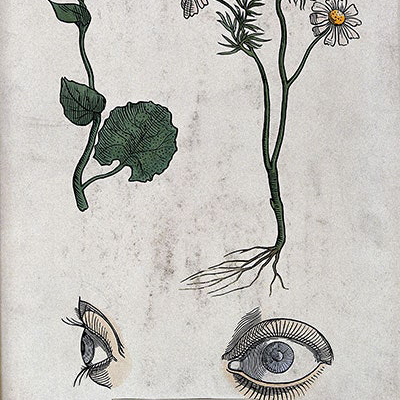

Moreover, the doctrine of signatures was combined with the humoral theory. The natural elements deeply affected the humours within the human body, causing imbalance and, therefore, illness. Fortunately, health could be restored using nature and her remedies: many plants were shaped like the organ or part of the body they could treat. So, if you had an eye disease, you could treat it with the aptly named plant eyebright, whose flower resembled a human eye. If the issue was jaundice, which caused the skin to turn pale and yellowish, saffron would be useful, while for brain-related problems, walnuts were indicated. For respiratory conditions affecting the lungs, the also aptly named lungwort plant would be helpful. You get the idea.

Legacy, Modern Influences, and Reassessing Folk Medicine

The doctrine of signatures might appear outlandish today. This all-encompassing, all-connected understanding of the world, exemplified by the doctrine of signatures, has arguably never been as dominant as it was during the early modern period. And even then, there were those who opposed it. By the 19th century, it was relegated to the domain of magic, with Victorian occultists creating tables of magical correspondence to map the network of symbols. However, many practitioners working outside the framework of orthodox, Western medicine, such as herbalists and homoeopaths, rely on some form of analogical thinking for their cures, indicating the long-lasting influence of the doctrine of signatures. Nicholas Culpepper’s herbal has virtually never been out of print since its publication in the mid-seventeenth century. And it is undeniable that interest in the doctrine of signatures encouraged many to study and research plants.

With the development of medical knowledge, as well as chemistry, botany, and pharmacology, researchers started to identify the active compounds in plants, making a plant’s appearance irrelevant to understanding its therapeutic use. Still, we should be mindful of judging our ancestors too harshly for their ‘outlandish’ beliefs.

Too often is popular knowledge about health derided as ‘folkloric’ and pertaining to the domain of ‘old wives’ tales’, itself a misogynistic expression. Of course, that does not mean that all of these medicines were effective. Indeed, some could even be harmful. The womb-resembling birthwort, which, as the name indicates, was used during pregnancy and childbirth, can cause cancer as well as kidney damage. Some of these ‘cures’ could indeed help though, and many of them were just innocuous.

As Michel Foucault wrote in The Order of Things, the symbolic and analogical thinking exemplified by the doctrine of signatures was crucial in how humanity structured the world around us. And, while it developed differently depending on time and place (think of traditional Chinese medicine or Ayurveda, both of which make use of this kind of reasoning), the idea of a network connecting all parts of nature, including humans, is ultimately a profoundly human belief.

References:

Jakob Boehme, The Signature of All Things: De Signatura Rerum (CreateSpace, 2017) (originally published in 1621).

Geronimo Cardano, De Subtilitate Libri XXI (Basel, 1554).

Giambattista Della Porta, Phytognomonica (Naples, 1588).

Paracelsus, Essential Theoretical Writings (Leiden, 2008).

Further Reading:

Ernst Cassirer, The Individual and the Cosmos in Renaissance Philosophy (Oxford, 1963).

Lawrence Conrad, Michael Neve, Vivian Nutton, Roy Porter and Andrew Wear, The Western Medical Tradition, 800 BC – 1800 AD (Cambridge, 1995).

Roy Porter, The Greatest Benefit to Mankind: A Medical History of Humanity from Antiquity to the Present (New York,1997).